CIRCULAR CAUSALITY

The Beginnings of an Epistemology of Responsibility

Heinz von Foerster

I shall speak in fragments, instead of in one piece, of some pieces of Warren McCulloch’s work, for through each of these pieces (should I say “monads”?) he and his work can be seen as a whole.

The pieces and period I wish to talk about fall into the immensely fruitful decade between 1943 and 1953. It is the decade of the catalytic conferences, those of the New York Academy of Science, the Macy Foundation, the Hixon Symposium, etc., of McCulloch’s formidable papers about a calculus of ideas, a heterarchy of values, how we know universal, etc., and of course, of the publication of Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics in 1948 at the midpoint of this period. It is the decade of a conspiracy, a “breathing together,” amongst a score of curious, fearless, articulate, ingenious and pragmatic dreamers who conformed in letting diversity be their guide. I am fascinated by the stream of concepts and insights, of invented relations, of perceptions, thoughts and ideas, of questions unanswered and answered that poured forth from these people.

Do we witness the emergence of a new paradigm, a model, a new way of seeing things at a different angle? No! What was talked about then was not a model of “something.” Seeing things at a different angle requires “things,” but there were none. The problem was not things, it was seeing. Here I shall talk about seeing.

I left Vienna for the United States and arrived on the Queen Mary in New York in February 1949. My luggage was minimal: a small suitcase, an Austrian passport with a visitor’s visa for three months, a minimal speaking vocabulary of English, and ten copies of a short monograph on memory I had written the year before, and which I was going to mail to old friends whom I had not seen for more than 15 years. The monograph: Das Gedachtnis: Eine quantenphysikalische Untersuchung.

For the benefit of their audiences, space trotters find the familiarity of home life, even when arriving at the remotest planets: all is the same, including language. Not so when going from Vienna to New York in 1949 — two worlds apart.

In the almost four years between the two great plagues (Hitler’s invasion and Stalin’s conquest), and my departure, life in Vienna had improved. Walking through the streets in convoys was no longer a necessity: at the few hospitals gone were the long lines of women, raped at gunpoint, now waiting for abortions: gone was the haunting fear that flooded mind and heart, that those friends who did not come on time had, as so many others, vanished without a trace, although they could just be late. Gone were the huge posters that had appeared when the Western allies joined the Russians in administering the affairs of Vienna. What posters? Enormous photographs taken in concentration camps: the mangled, emaciated, naked corpses tossed onto a pile; the caption: “This is your responsibility.”

I had to explore New York immediately the night I arrived. Times Square, flooded in light, people pouring from theaters, restaurants, bars, busy stores, cars squeezing through crowded streets, sailors, minks, beggars, posters up in the air. What posters? One very high up, 500 square feet of an enormous photograph of the face of a man smoking a cigarette, puffing real smoke. The caption: “Smoke Camels.”

A telegram from Chicago three days later was the first response to my mailings: “Want to know more about your monograph. Come at once.” Capital Airlines had a night flight for $18.00 leaving New York soon after midnight, arriving in Chicago at six in the morning. At nine I was at the Neuropsychiatric Institute of the University of Illinois’ Medical School and met the man who wanted to know more: tall, lanky, a grayish beard, an inviting grin, and the eyes! Eyes to support the Greek notion of vision. It is not the light that enters but sight that beams forth from the eyes, touching with joy what they see. So I met Warren McCulloch.

We go immediately into my paper; the assumptions, the mathematics, the results. I have the feeling that we are inventing the whole story then and there, every step an adventure, every understanding a celebration. My small linguistic aperture is no obstacle (I sense this with growing wonderment). That day 1 learned two things. First: my theory’s numerical consequences came close to the physiologist’s hope that such numbers could be derived from some general notions, notions whose significance I was then unaware of: and second, that these notions (“feedback,” “closure,” “circularity,” “circular causality,” etc.), are conditions sine qua non, the seeds, the nuclei for a physiological theory of mentation. Moreover, McCulloch invited me to present my story three weeks later at the “Macy meeting,” and told me to read at once a recently published book, Cybernetics, by Norbert Wiener (1).1

That meeting was The Sixth Conference on Circular Causal and Feedback Mechanism in Biological and Social Systems, held in New York on March 24-25, 1949. The host, the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, whose major contribution to medical research was its Conference Program. A dozen or so of critical topics,2 each discussed by about two dozen conferees of various competences or disciplines attended five annual (or biannual) conferences allotted to each topic, with guests invited for one or more meetings.

If not the word “interdisciplinary,” then the concept may well have been invented by Frank Fremont-Smith, the Foundation’s conference program director, a gregarious elitist who sensed and set a trend in medical research by recognizing and bringing together people with new ideas, and supplying them with the financial and organizational apparatus of his foundation for holding such conferences.

McCulloch was the chairman of the conference I was now to attend, and I was to become part of a myth. A small part indeed. A kind of Aristodemus who was at a gathering of friends celebrating Agathon, — the fabulous symposium at Agathon’s house. Aristodemus could not quite remember precisely what was said when he tried to describe the events of that night to Apollodorus. So what we know today (if we can trust Plato) is only through Apollodorus who admits he had to make up for this and that slip of his memory when he re- told it to Glaucon while walking with him from Phalerum to Athens. “How long ago was this celebration?” asks Glaucon, assuming it was just recently. But it could not have been. Probably it was long ago. Most of those who were there are no longer around.

Like its early precursor in Athens whose participants were the sensors, shapers and movers of an integral sense of thought, language and action (today only comprehensible within the scheme of narrow categories; “philosophy,” “poetry,” “politics,” etc.), the New York meeting gathered minds that were the sensors, shapers, and movers of a new sense of science, of a new “scientific paradigm,” as such changes of perception were referred to two decades later (2).

However, unlike the meeting in Agathon’s house, there was no orderly sequence of presentation, no way to find out who would speak next or what he would say. Instead there was a continuous stream of dialogue among people who asked, listened, told, clarified, doubted, argued, admonished, supported, admitted ignorance, hypothesized, erred, and who vastly enjoyed maintaining that continuous stream of dialogue. At first I was not quite sure what all these people were conversing about. In fact, it looked to me as if that discussion was a ping-pong game, played with only a single ball by the twenty participants as fast as one could play - but not so fast that the ball could not be returned. Of course, my comprehension grew during the meeting; for moments I thought I knew. But I sensed that there was something that drove this group on and on, something that I was missing.

Kindness and politeness interrupted the ping-pong game when I was asked to report on my theory of memory (which I stumblingly did). Afterwards, the game was immediately continued, first with my theory as the ball, later shifting to more general aspects of recognition and recall.

I, as guest, was not included in the business meeting that night. But when I was called in again the chairman, Warren McCulloch, announced to me that because of my poor English they had been trying to find a way for me to acquire this language fast and efficiently. They had found it, I was told, they were appointing me editor of the Proceedings of this conference, to be published as soon as possible. I was flabbergasted! When I could speak I said that since I felt that the title of the conference was too cumbersome: “circular-causal-and- feedback-mechanisms-in- biological-and-social- ”, I wondered whether this conference could not simply be called “Cybernetics,” with the present title as subtitle. When this motion was immediately and unanimously accepted with laughter and applause, Norbert Wiener, eyes wet, walked out of the room to hide his emotion.

Four weeks later I received a stack, three inches thick, of legal sized green pages, the transcript of the steno-recordings typed during the conference by a most remarkable lady stenographer. At the very beginning of the conference she asked that everyone should say his name with a few words added for voice identification. During this exercise she had her eyes fixed to the ceiling, giving the appearance of a blind woman. After that she prefixed every utterance during the entire conference with three letters indicating the speaker with no single error I could discover.

* * *

Working through the transcript at my own speed I began to see what was beneath the polished surface of the dialogue, polished by all the previous dialogues until it was “smooth as a Brancusi egg” as McCulloch called it, and also kept it this way. He finally told us in his summary at the last Macy conference [110]: “I am compelled to watch your faces and to guess, before I let you have the floor, whether you will speak to the point or not, and from which side of the fence. With malice aforethought I have given the malcontent the floor, because he doubted, or disagreed, however unreasonably. Before I knew you so well this happened by accident, but as time went on, and we learned one another’s languages, I learned that it was the best way to keep our wits on their toes.”

I saw, and saw it ever more clearly at later conferences, that beneath the discussing psychological moment, neurotic potential, sensory prosthesis, digital notions in the central nervous system, maze solvers, homeostasis, mechanical chess players that outplay their designers, learning in the octopus, the growth of enormous helmets in freshwater crustaceans, reduction of the number of possible Boolean functions, nucleocytoplasmic feedback systems in Paramecium Aurelia, measures of semantic information, communication among animals, humor, meaning, learning in wasps and ants, narcolepsy, hypnosis, grief, laughter, circular causality, and much more - a door was being pushed open slowly, but forcefully, to let in one who, in orthodox science, was excluded from all these investigations: the investigators; the observer; me, who now asks, “who am I?”

* * *

“But let us compel our physicist to account for himself...” suggests McCulloch in one of the introductory paragraphs of Why the Mind is in the Head [98]; and he continues:

In all fairness, he must stick to his own rules and show in terms of mass, energy, space and time how it comes about that he creates theoretical physics. He... will be compelled to answer whether theoretical physics is something which he can discuss in terms of neurophysiology. To answer “no” is to remain a physicist undefiled. To answer ”yes’ is to become a metaphysician - or so I am told.

It is this paper, a very ambitious paper, that he read to the participants of the Hixon Symposium (3), a small group of leading neurophysiologists, psychiatrists, and experimental psychologists with John von Neumann, the mathematician, the inside outsider. Most of the participants knew, or knew of, the McCulloch-Pitts paper, A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity [51], published five years earlier, and also of the other crucial contribution of a year before, How We Know Universals: The Perception of Auditory and Visual Form [76] by Pitts and McCulloch. In fact, John von Neumann in his opening talk gave full credit to the earlier paper on the logical calculus of ideas. He devoted a whole section to Formal Neural Networks and to “...the remarkable theorems of McCulloch and Pitts on the relationship of logics and neural networks.”

The stage is set, and McCulloch’s talk following von Neumann’s catapults into a grand panorama, weaving anew the magnificent tapestry of interrelation between logic, neural activity, neural organization, computation, perception, cognition, will and consciousness, as well as the limits of entities built and the potential of creatures begotten.

Or so it appears when one is looking at the pattern on the front of that tapestry. However, check its back for how it holds together, it becomes clear that he has taken the physicist’s part who answered “yes” when asked to account for his physics with neurophysiology, i.e., to account for himself. Was this, therefore, an essay in metaphysics? Most certainly not in the orthodox sense. It was a display of the contextual fabric within which we may speak of reflection; that is, seeing oneself through oneself; that is, causing oneself, the shortest causal loop. Knowing one’s knowing, an epistemology of how we know, not what; an experimental epistemology.

Not metaphysics, but epistemology was at the core of this lecture. Metaphysics, and not epistemology, however, is what some of the participants thought they had heard, and among these, some did not like it: “Dr. McCulloch’s explanation... introduces more histological assumptions ad hoc than seem compatible with usual standards of plausibility,” (3). A major discussion developed which (in transcript) was more than four times as long as the paper. Questions were asked whose answers generated ever more questions until Hank Brosin, a skillful chairman of gentle wisdom, returned the floor to McCulloch for a major reply.

The reply was about half the length of the formal presentation given before. The reply had no title. But if there had been one, it might have been, Why I Mind What’s in the Head, for here he tells us what moved him to see the way he sees. He opens with a reminder: “If you will remember, I suggested that we ask the theoretical physicist to account for himself...” and then he tells us how he, Warren McCulloch, accounts for himself. “I believe...”, “I think...”, “I don’t think...,” “I would try...”, “I am sure...”, and so on, referring more than a hundred times to himself, while in his formal paper he does so only twice, including this final sentence: “The job of creating ideals, new and eternal, in and of a world, old and temporal, robots have it not. For this my mother bore me”.

* * *

I do not know when Warren McCulloch first met Frank Fremont-Smith. It could well have been in 1942 when McCulloch participated in a conference on central inhibition in the nervous system, sponsored by the Macy Foundation. Norbert Wiener says in his introductory, essentially historical chapter to Cybernetics that it was at this meeting that he, together with Julian Bigelow and Arturo Rosenblueth distributed a draft of what later became their seminal paper, Behavior, Purpose and Teleology (4) which was published the following year, the same year that saw the publication of McCulloch and Pitts’ calculus of ideas [51]. Soon afterwards John von Neumann joined this group, and early in 1944 arranged a most fruitful meeting3 in which “...engineers, physiologists, and mathematicians were all represented” (1). “But,” as Wiener continues, “Drs. McCulloch and Fremont-Smith have rightly seen the psychological and sociological implications of the subject, and have co-opted into the group a number of leading psychologists, sociologists, and anthropologists”.

This was what set the ten Macy Conferences in motion (1946-1953). Of the first five, alas, there are no records, either published or in the files of the foundation: and the published transactions of the last five (5), (6) have long been out of print. They have become an “oral tradition,” a myth. Complementary to the Macy Meetings, and sandwiched between them, were two other conferences, most likely stimulated by the Macy Meetings’ catalytic action. One was the Hixon Symposium (3) mentioned earlier, and the other was the conference on Teleological Mechanisms, sponsored by the New York Academy of Sciences, including Norbert Wiener, Evelyn Hutchinson, W.K. Livingston, and Warren McCulloch as the speakers. In the Annals of the Academy (7) a foreword by Lawrence K. Frank is added to their papers. The first lines of this foreword of more than thirty years ago, perplexing as they may sound, provide a historical context: “The title of this conference, Teleological Mechanisms, may be somewhat perplexing or difficult to accept to some who are encountering it for the first time.”

One might have expected Norbert Wiener to take the title of this conference as the central theme of his opening address. But telos, goal, purpose, appear only peripherally in his presentation, Time, Communication, and the Nervous System. Its main thrust was to demonstrate a link between the unidirectional flow of events in statistical thermodynamics with the unidirectional flow of events in communication. It was to become a cornerstone in the development of what is now called “information theory” (8).

The other speakers, however, squarely took on the theme of the conference: Circular Causal Systems in Ecology (Hutchinson); The Vicious Circle in Causalgia (Livingston); and finally, Warren McCulloch spelled out the central questions of a twentieth century teleology (81): “What characteristics of a machine account for its having a Telos, or end, or goal? And what characteristics of a machine define the end, or goal or Telos?”

In this address, as on two other occasions, he gives a historical perspective to the fate of Aristotle’s fourth category of cause, causa finalis, the final cause, the succubus of the concept of Telos. in its use from pre-aristotelian times to the present. In contrast to the historian of science who could write, “Ptolemy believed..., but we know...”, Warren McCulloch, the scientist seeing himself in the past, tells us, “Ptolemy knew..., but we believe...”.

The two other occasions for such flashbacks are McCulloch’s accounts of the last Macy conference (109), and his farewell to all participants, concluding the series of immensely stimulating and constructive conferences. He calls it Summary of the Points of Agreement Reached in the Previous Nine Conferences on Cybernetics [110].

As with other men, who, at the end of their efforts knew that they knew, and allowed this vision to cloud their insight with melancholy: "Whereof we cannot speak thereof we must remain silent" (the last proposition in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus. (9)), so McCulloch’s sense of responsibility made him voice his apprehension that the successful and celebrated brain children of this group might be misbegotten. His last words of farewell were: “It is my hope that by the time this session is over, we shall have agreed to use very sparingly the terms “quantity of information” and “negentropy.””

I have no doubt that Warren McCulloch, the experimental epistemologist, sensed that his warnings might not be heeded, as is shown by the outcome of an experiment of his own design [109]:

Ten years ago I tried an experiment. There was a meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in Detroit. I was then intrigued by the Lear Komplex. which is the subject of a paper coming out of Vienna concerning the play of King Lear, and it proves that Mrs. Lear is the all-important person, because she is not once mentioned. My experiment was the following: In the hotel in Detroit there was a rather large and comely bear. Drs. Frank Fremont- Smith and Molly Harrower cottoned on to the bear and they paraded it through the hotel. They gave me the idea of what I think is the nicest of all yarns I have ever invented. The story is the following. They brought the bear to the conference room. One psychiatrist after another would look at the bear sitting among them, and then snap his head back to the front. You could count ten, and each one would take a second look and snap his head back to the front. Several years later I asked Drs. Fremont-Smith and Harrower whether any of the psychiatrists had said anything to either of them about seeing a bear at the meeting. They said. “No.”

I have told this story wherever psychiatrists were gathered together, and shall continue to tell it. My esteemed friend. Dr. Alexander Forbes, heard me tell the story and at once went to Dr. Harrower and asked. “Did you really have a bear at the meeting?” She replied. “No.”

Footnote

Appendix I

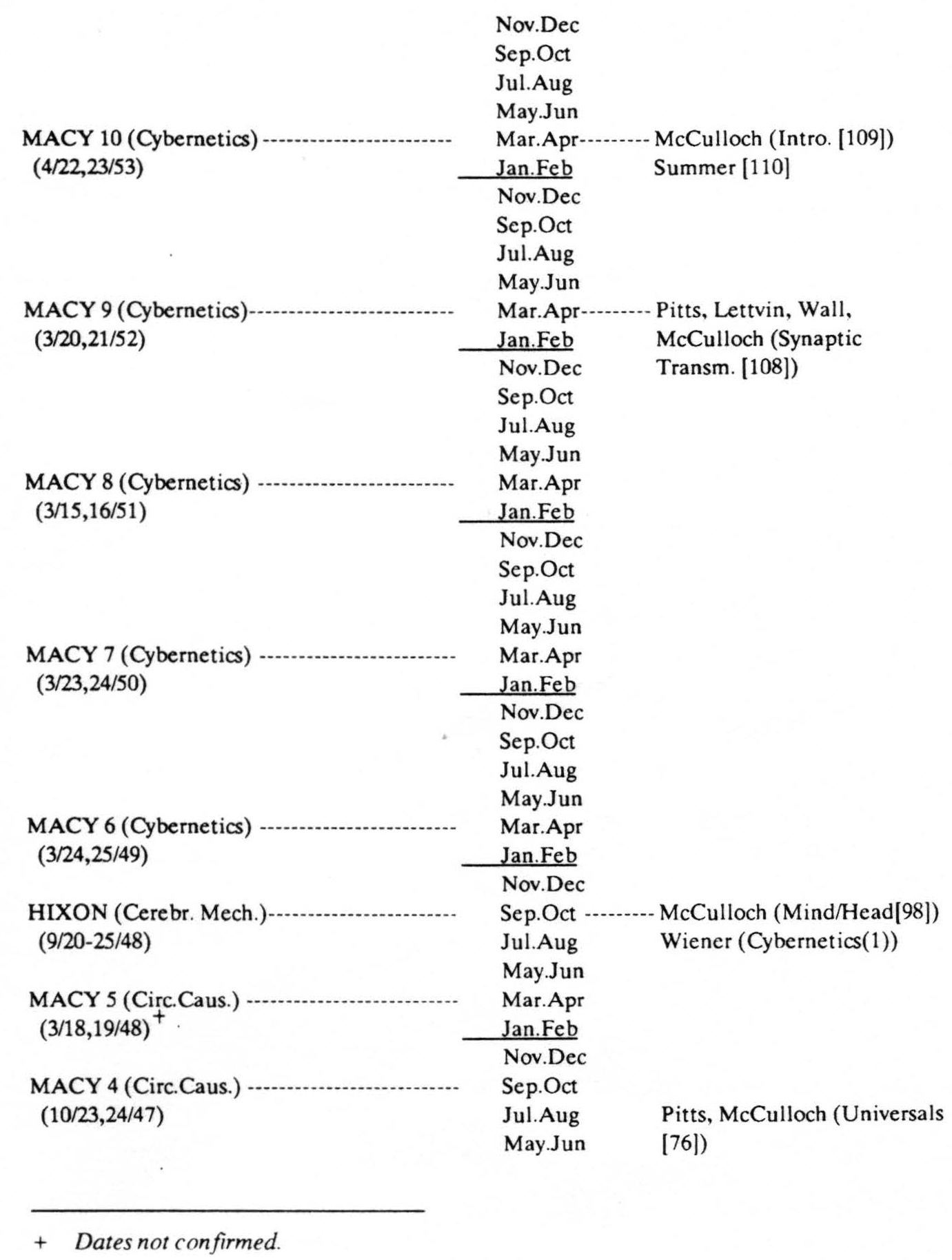

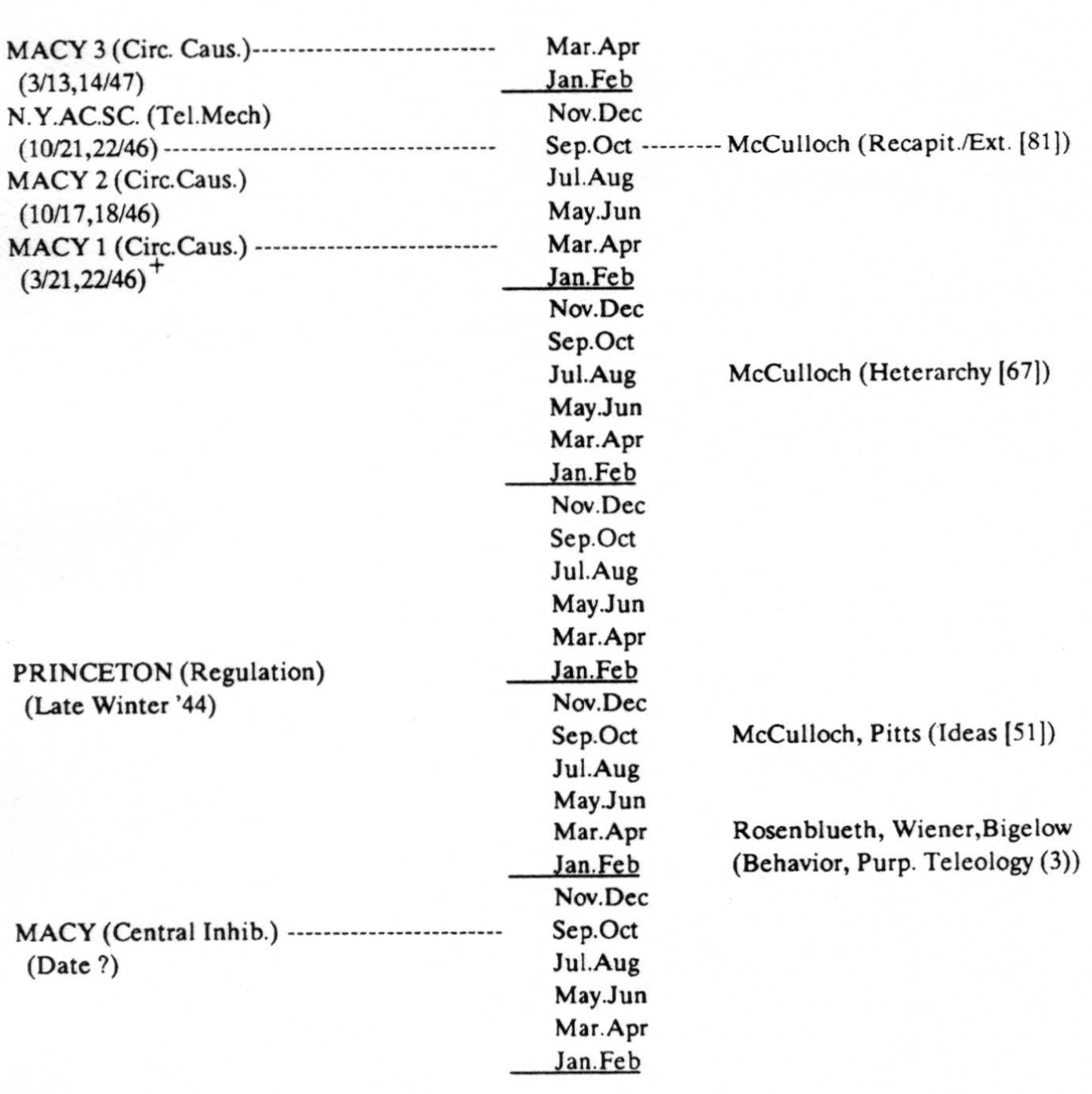

Timetable of meetings (left) and publication of papers [ ] (right) which are closely tied to matters cybemetical. Abbreviated titles (Abbr) by McCulloch and co-authors are given together in parentheses (Abbr [#]) with the entry # of the McCulloch publication catalogue. Papers by other authors (Abbr) (#) are referred to Appendix III, REFERENCES.

Appendix II

Participants at Meetings

Numbers n following names indicate participation (G=guest) in the n-th Conference on Circular Causality (or Cybernetics) of the 10 conferences on this topic sponsored by the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation between 1946 and 1953; letter H indicates attendance at the Hixon Symposium, September 20-25, 1948; and letters NY participation in the conference on Teleological Mechanisms sponsored by the New York Academy of Sciences on October 21 and 22, 1946. However, since the Macy Foundation destroyed almost all the records of its Conference Program, and since the transactions only of conferences number 6-10 of the Cybernetics series were published (including a list of participants) names of participants of Conference 1-5 were gleaned from Norbert Wiener’s Cybernetics (1) (see p. 27 ff) and from a letter (unpublished) by Warren S. McCulloch, Chairman, to all members of the Fourth Macy Conference on this topic (10/23,24/1947) entitled An Account of the First Three Conferences on Teleological Mechanisms, a title alternately used for Circular Causality. Hence, the absence of any numbers 1-5 in the entry for each participant does not necessarily indicate their absence at any one of those conferences, but only that the above two sources make no explicit reference to their presence.

Harold A. Abramson..........................................................6 Department of Physiology, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, New York, N.Y.

Ackerman............................................................................3

Vahe E. Amassian...............................................................10 G Department of Physiology & Biophysics, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, Wash.

W. Ross Ashby.....................................................................9 G Department of Research, Barnwood House Gloucester, England

Y. Bar-Hillel...........................................................................10 G Department of Philosophy, Hebrew University Jerusalem, Israel

Gregory Bateson.................................................................1, 6, 7, 9, 10 Veterans Administration Hospital Palo Alto, Calif.

Alex Bavelas.........................................................................7, 8 Department of Economics & Social Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Mass.

Julian H. Bigelow..................................................................7, 8, 9, 10 Electronic Computer Project Institute for Advanced Study Princeton, NJ.

Herbert G. Birch...................................................................8 G Department of Psychology City College of New York, N.Y.

John R. Bowman..................................................................8 G, 9 G, 10 G Department of Physical Chemistry Mellon Institute of Industrial Research University of Pittsburg, Pittsburg Penn.

Henry W. Brosin...................................................................3, 6, 7, 8, 10, H Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinics Pittsburg, Penn.

Yuen Ren Chao.....................................................................10 G Department of Oriental Languages, University of California, Berkeley, Calif.

Jan Droogleever-Fortuyn.....................................................10 G Department of Neurology University of Groningen Groningen, Holland

M. Ericsson.............................................................................1 New York

Fitch........................................................................................3

Lawrence K. Frank................................................................6, 7, 8, 9, 10, NY, H 72 Perry Street New York, N.Y.

Frank Fremont-Smith..........................................................6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Medical Director Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation New York, N.Y.

Ralph W. Gerard..................................................................6, 7, 8, 9, H Department of Physiology School of Medicine University of Chicago Chicago, IL.

W. Grey-Walter....................................................................10 G Burden Neurological Institute Stapleton, Bristol, England

Ward C. Halstead.................................................................H Professor of Experimental Psychology University of Chicago Departments of Medicine and Psychology

A Van Harreveld...................................................................H Professor of Chemistry California Institute of Technology

Mollie Harrower..................................................................1, 3 Psychologist New York, N.Y.

Donald Herr.........................................................................NY Control Instrument Company, Inc. Brooklyn, N.Y.

George Evelyn Hutchinson................................................6, 7, 8, 9, 10, NY Department of Zoology Yale University New Haven, Conn.

Lloyd A. Jeffress..................................................................H Professor of Psychology University of Texas Hixon Visiting Professor California Institute of Technology, 1947-1948

Heinrich Kluever.................................................................1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, H Professor of Experimental Psychology Division of the Biological Sciences University of Chicago

Wolfgang Koehler................................................................H Research Professor of Philosophy and Psychology Swarthmore College

Lawrence S. Kubie...............................................................1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Department of Psychiatry and Mental Hygiene Yale University School of Medicine New Haven, Conn.

K.S. Lashley...........................................................................H Research Professor of Neurophysiology Harvard University

Paul Lazarsfeld.....................................................................1 Department of Sociology Columbia University, New York, N.Y.

Kurt Lewin.............................................................................1, 2 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Mass.

J.C.R. Licklider........................................................................7 G Psycho-Acoustic Laboratories Harvard University Cambridge, Mass.

H.S. Liddell...........................................................................6, H Professor of Psychobiology Cornell University

Donald B. Lindsley..............................................................6, H Professor of Psychology Northwestern University

WK Livingston.....................................................................2, N.Y. Department of Surgery University of Oregon Medical School Portland, Oregon

David Lloyd..........................................................................3, 6 Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research New York, N.Y.

Rafael Lorente de Nó...........................................1, 9, H Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research New York, N.Y.

Duncan Luce........................................................................9 G Research Laboratory of Electronics Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Mass.

Donald M. MacKay...............................................................8 G Department of Physics, King’s College University of London London, England

L.A. MacColl.........................................................................NY Bell Telephone Laboratories New York, N.Y.

Donald G. Marquis.............................................................3, 7, 9, 10 Department of Psychology University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Mich.

Warren S. McCulloch.........................................................1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, H, NY Research Laboratory of Electronics Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Mass.

Turner McLardy...................................................................7 G Maudsley Hospital Denmark Hill, England

Margaret Mead....................................................................1, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, NY American Museum of Natural History New York, N.Y.

Frederick A. Mettler..............................................................6 Departments of Anatomy and Neurology College of Physicians and Surgeons Columbia University New York, N.Y.

Marcel Monnier....................................................................9 G Department of Medicine Laboratory of Applied Neurophysiology University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

Oscar Morgenstern..............................................................1 Institute for Advanced Study Princeton, N J

J.M. Nielsen........................................................................H Clinical Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry University of Southern California

F.S.C. Northrop.....................................................................1, 9, 10 Department of Philosophy Yale University New Haven, Conn.

Linus Pauling........................................................................H Professor of Chemistry California Institute of Technology

F.H.Pike.................................................................................NY Columbia University New York, N.Y.

Walter Pitts..........................................................................1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Research Laboratory of Electronics Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Mass.

Henry Quastler....................................................................9 G, 10 G Control Systems Laboratory University of Illinois Urbana, Ill.

Antoine Remond..................................................................9 G Neuropsychiatric Institute University of Illinois College of Medicine Chicago, Ill.

Ivor A. Richards.....................................................................8 G Graduate School of Education Harvard University Cambridge, Mass.

David McKenzie Rioch.........................................................8 G, NY Division of Neuropsychiatry Army Medical Service Graduate School Army Medical Center Washington, D.C.

Arturo S. Rosenblueth.........................................................1, 2, 8, 9 Department of Physiology and Pharmacology Instituto Nacional de Cardiologica Mexico City, D.F., Mexico

Leonard J. Savage.................................................................6, 7, 8, 10 Committee in Statistics University of Chicago Chicago, Ill.

Theodore C. Schneirla.........................................................2, 6, 10 American Museum of Natural History New York, N.Y.

Claude Shannon.................................................................. 7 G, 8 G, 10 G Murray Hill Laboratory Bell Telephone Laboratories, Inc. Murray Hill, N.J.

John Stroud...........................................................................6, 7 G, H U.S. Naval Electronic Laboratory San Diego, Calif.

Hans Lukas Teuber...............................................................6, 7, 8, 9,10 Department of Neurology New York University College of Medicine New York, N.Y.

Mottram Torre......................................................................9 G Personnel Division Mutual Security Agency Washington, D.C.

Gerhardt von Bonin............................................................ 1, 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 10, NY Department of Anatomy University of Illinois College of Medicine Chicago, Ill.

Heinz Von Foerster..............................................................6, 7, 8, 9, 10 Department of Electrical Engineering University of Illinois Urbana, Ill.

John Von Neumann.............................................................1, 2, 3, 7 H Department of Mathematics Institute of Advanced Studies Princeton, NJ.

Paul Weiss ............................................................................H Professor of Zoology University of Chicago Chicago, Ill.

Heinz Werner.......................................................................7 G Department of Psychology Clark University Worcester, Mass.

Norbert Wiener...................................................................1, 2, 3, 6, 7, NY Department of Mathematics Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Mass.

C.A.G. Wiersma....................................................................H Professor of Physiology California Institute of Technology

Jerome B. Wiesner..............................................................9 G Research Laboratory of Electronics Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Mass.

Lowell Woodbury................................................................H Assistant Professor of Physiology University of Utah Medical School

J.Z. Young............................................................................9 G Department of Anatomy University College London, England

References

Wiener, N.: Cybernetics, John Wiley & Sons, New York, (1948).

Kuhn, T.: The Structure of Scientific Revolution

Jeffress, L.A. (ed): Cerebral Mechanisms in Behavior. (The Hixon Symposium); John Wiley & Sons, New York (1951).

Rosenblueth, A., N. Wiener and J. Bigelow: Behavior, Purpose and Teleology, Philosophy of Science. 10, 18-24 (1943).

Von Foerster, H. (ed): Cybernetics. Circular Causal and Feedback Mechanisms in Biological and Social Systems (Transactions of the Sixth Conference) The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, New York, (1950).

Von Foerster, H., M. Mead and H. Teuber (eds): Cybernetics. Circular Causal and Feedback Mechanisms in Biological and Social Systems (Transactions of the Seventh, Eighth, Ninth and Tenth Conferences). The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, (1951, 1952, 1953, 1955).

Miner, R.W. (ed): Teleological Mechanisms. An. New York Academy of Science. 50 (4) 198-278 (1948).

Wittgenstein, L.: Tractatus Logico Philosophicus. The Humanities Press: New York, (1961).

Shannon, C. and W. Weaver: The Mathematical Theory of Communication. University of Illinois Press, Urbana, (1949).

For further research:

Wordcloud: Account, Asked, Cambridge, Causal, Chicago, Circular, College, Conference, Cybernetics, Department, Foundation, Ideas, Institute, John, Knew, Laboratory, Later, Macy, Mass, Massachusetts, McCulloch, Mechanisms, Medical, Medicine, Meeting, Norbert, Numbers, Ny, Paper, Participants, Physiology, Professor, Psychology, References, Research, School, Science, Seeing, Sense, Systems, Technology, Teleological, Title, Told, University, Warren, Wiener, Years, York

Keywords: Conferences, Science, Decade, Papers, Foundation, Companion, Causality, Mind, Group

Google Books: http://asclinks.live/piir

Google Scholar: http://asclinks.live/zt5w

Jstor: http://asclinks.live/e4c4