PHYSIOLOGICAL PROCESSES UNDERLYING PSYCHONEUROSES1 [90]

W.S. McCulloch

Introduction

I am inclined to sympathize with the good Saint Thomas Aquinas, that patient ox of Sicily, who lost his temper and died of the ensuing damage to his brain, when he met in Siger of Brabant the arch-advocate of two incompatible truths. In his time the schism was between revelation and reason, as in ours it is between psychology and physiology in the understanding of disease called ‘mental'.

As we follow down the long trail of neurophysiology from Alcmaeon to Sir Charles Sherrington, we find it leading blindly to the conclusion that ‘in this world Mind goes more ghostly than a ghost'. It were tedious to trace the alternative tradition, which begins in Plato's political psychology, conceived in the image of the state to end in Freud's trichotomy of the soul. His epigoni, the latter day illuminati, those new perfectibilians, have dethroned reason but to install social agencies, analytic interviews and transference in the places of espionage, confession and conversion, and fail to add a cubit to our stature. Just as Galileo and the Inquisition were both wrong in the one thing they both believed, that motion is absolute, so these two warring sects both accept as real the separation of body and mind, although there is none in nature. If it were real, it could not be bridged by coining compound adjectives out of ‘psyche’ and ‘soma'. .

The real bridge we have is the science of signals, newly developed out of the art of communication. For a signal has a double nature; it is a physical event, which happens only once in a singular world, yet it is essentially capable of being true or else false. Whether the signals are closures of telegraph-relays or impulses in neurons, it is possible for the nets they traverse to have general ideas, in the sense of recognizing universal presented in experience shorn of accidental peculiarity. In recent papers we have shown how nets perform this function in the superior colliculus and in certain parts of the cerebral cortex.

Signal-bearing nets also exhibit purposes in the sense of ends in operation. A purpose is given in any condition of the inputs to a net, such that a deviation from it produces a change in the output that, directly or indirectly, returns into the input so as to reduce the deviation from the chosen condition. In physics, we should call this a state of stable equilibrium. Some circular paths lie wholly inside the nervous system; thus, as cortical excitement increases, the indirect paths returning from it to the thalamus inhibit the further transmission of signals to the cortex. Other circuits go outside the nervous system, but stay inside the organism. This is true of the reflex, defined by Magendie and Bell as a process begun by a change in some part of the body, initiating impulses that proceed over dorsal roots to the spinal cord, whence they are reflected over ventral roots to the part where they arise, and there stop or reverse the change from which they spring.

In our appetitive circuits, only part of the path lies within us, the rest outside us in the world. These, cast in the molds of our ideas, mark out what we call purposive behavior. They are error-operated, driven toward their goals by some measure of the difference between the end and its attainment. It is the same device which the engineer uses routinely under the name of a servomechanism, whenever he wants to embody purpose in a machine. It would be strange indeed if he, himself, worked on a very different principle.

As psychiatrists, it is natural for us to try to carry the analogy further. If animal anjl machine operate in the same way, they ought to suffer from some of the same diseases, or gremlins, as the engineer calls them, namely, the ones common to all circular mechanisms. The diseases of such systems, the gremlins, defy dimensional analysis. Energy, time, and length are not their measures. Pure numbers and the logarithms of numbers are but the ground on which they figure. At the moment, I am not concerned with finding out their precise anatomical location. The properties of nervous circuits are greatly affected by changes in quite different ones which may have a part in common with them. The central nervous system performs nearly all its operations many times over in parallel, and proceeds to the next step according to a general agreement of its signals. If one part is disordered or preoccupied, it performs the same function elsewhere. Of the input it receives, it filters out and discards all but one part in 10'. It is not surprising that it should defy the best neurologist, for all but the grossest defects. That is their misfortune and not yours.

On more than one occasion I have said, not quite in jest, that in their essence gremlins and neuroses are demons, sentient and purposive beings, exercising in their own right properties more mental and more physical than any psychoanalyst has yet had the courage and clarity to claim for them, as much when they haunt machines as men. I speak tonight of the nature of demons.

Half-way between the inner feedbacks of the brain, whose diseases are convulsions, tremors, and rigidities, and those outer, appetitive disorders that frequent the public world, be they ‘isms’ or neuroses, there is one particular demon I shall describe at length, partly because he produces wellnigh intolerable suffering, and partly because his ways and doings are better known than those of any other. He is called causalgia - burning pain. I do not say this demon is all soul, though you will find him embodied now one place and now another. To torture us at all he must exist somewhere, somehow, as a perversion of some function in some nervous structure.

Causalgia begins as a perversion of a reflexive circuit. If you thrust a hand into hot water, or into water so cold that it seems to burn, the sensory receptors for pain and extreme temperature are excited. Their impulses, coming by fine fibres of the sensory roots to their own segments of the cord, excite the small internuncials that play upon preganglionic neurons of the sympathetic system. These, in turn, excite the sympathetic ganglia whose axones, running in mixed nerves and plexus about blood vessels, descend to the burning hand. Their barrage shunts the blood from the skin through the muscle and the bone, thereby conserving temperature within by decreasing the thermal conductivity of the skin. To maintain the proper temperature of the affected part is the function of this reflex. Its perversion is causalgia.

Let us see how the perversion happens. We used to demonstrate by placing a clamp upon the left internal mammary artery how changes in the circulation of a portion of a nerve may alter its excitability: for then the left phrenic nerve responds with a hiccup to the heart's electrical systolic pulse. We are all familiar with the paraes- thesia and the cramp that comes from sitting on the blood supply of the proximal portion of the sciatic nerve. The standard history , of causalgia is injury to nerve sufficient to damage, but not to sever it. Thereafter it responds to almost anything.

In 1944, Granit stimulated the sympathetic fibers to a limb of a cat, and recorded the afferent impulses from it to the cord, before and after crushing the mixed nerve. The experiment is easily repeated, and the outcome what you would expect: only after the injury, a volley of impulses over the post-ganglionic sympathetic fibers provokes a volley returning by the dorsal root. From what we know of cross-talk of signals generally, we should expect coupling to occur principally between conductors of comparable resistance and capacity, and, consequently that sympathetic efferents, being fine fibers, would excite fine-fiber afferents reporting pain and temperature from the peripheral distribution of the affected nerve. We do not need to jump from fibers to sensations, or from cats’ brains to men's. Earl Walker, in curing causalgia of the arm, cut all preganglionic fibers of the cervical sympathetic chain, leaving the peripheral connections intact, and delivered the chain itself into a glass tube through the wound. The patient, on coming out of anesthesia, was without his pain; but for several days, as long as the ganglia were still somewhat alive, stimulation of the chain evoked again the burning pain in the old place. «?

This, then, is how the reflex was perverted. Injury to the nerves permitted crosstalk from the post-ganglionic sympathetic nerves to the nerves reporting burning pain. This is a vicious circle. Efferent impulses which should have decreased the number of afferent impulses have increased their number. The reflexive circuit has become regenerative. This is a self-perpetuating active memory projecting the pain upon the peripheral distribution of the afferent nerve that it invaded. When the injury is recent, and the nerve healing well, causalgia may be terminated by temporarily blocking the reverberation in any part of the closed path. But if the wound remains an artificial synapse, the trouble starts again. What is far more interesting is that sometimes simply blocking the nerve distal to the lesion relieves or terminates causalgia, for this bespeaks the role of other afferents in maintaining a background of activity in the internuncial pool.

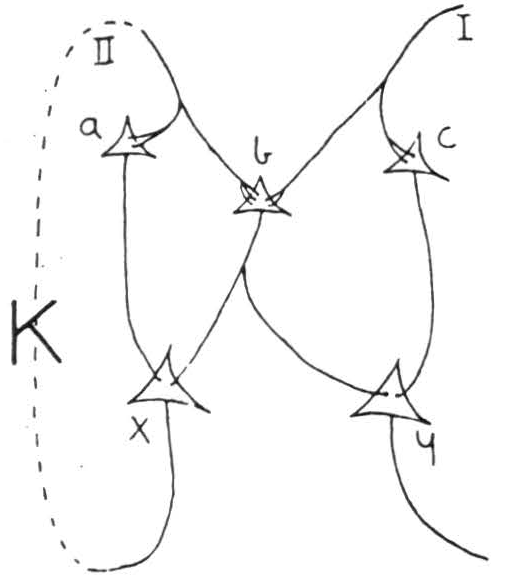

Now the patient keeps his white and glossy hand moist and cool, for every jolt, touch, rub, or tickle turns to burning pain. How came this perversion of sense? Strike the back of your hand against your chair and attend to the sensation. There is first a quick pain carried by fast fibers, then the late burning pain which comes by the fine fibers slowly to the cord. Whenever we do anything vigorously, these impulses are present, but the faster tactile or proprioceptive fibers get their impulses first to the cord, where they determine the pattern of internuncial activity before the impulses for burning pain arrive. In causalgia, the story is reversed. The painful impulses are always there, and all other impulses augment the process already under way. Here is Gasser's diagram of how such things can happen. Suppose the threshold of each neuron is just two synchronous impulses upon it. Then afferents of system I will fire b and c in phase and these will converge on y to fire it. But now let II get under way, and b will be swept into phase with a, convergence will occur on x, and it will fire. If this happens, the threshold of b must rise until I, which has but two synapses upon b, will become unable to fire b at any time. II has stolen the necessary internuncial b from I. But in causalgia, x feeds back to II and shuts I out forever. Obviously the scheme is oversimplified. I has many synergic fellows, and if enough of them can be got going at a time, they may be able to steal b from II and so

Figure 1. Gasser's diagram

break up causalgia. Among the best results that I, myself, have seen in the treatment of causalgia are Livingston's cases, in which good surgery of the wound was combined with early consistent and powerful persuasion to make use of these other afferent paths. He provided his patients with a whirlpool, into which they could put the painful part while they, themselves, controlled its rate of stirring. Those who were able to get other sensations through their burning pain usually recovered without further surgery. Here, at the reflex level, a kind of psychotherapy, by which I mean a use of afferent channels adequately stimulated, has exorcised the devil.

Unfortunately, if we wait too long, this method, as well as temporary and permanent nerve-blocking and section of the dorsal roots and section of the sympathetics fail, for the devil has moved into the cord. That he has not yet gone higher is clear; for spinothalamic section at that time will shut him out of our heads. I remember such a case after bilateral tractotomy and blocking of nerve proximal to the lesion. His affected foot was still obviously the recipient of a sympathetic barrage, which could come from no other thing than persistent activity reverberant in the cord. At this stage, instead of cutting the spinothalamic paths, the limb may be cut off - I have seen it done only too often - and it but substitutes a painful phantom for the real limb whereon the pain was formerly projected. This state has been imitated in experimental animals by Dr Margaret Kennard, who injected alumina cream into the sack around the cord. This produces no lesion apparent grossly or microscopically with ordinary stains. Yet the beast behaves as if he had causalgia of the corresponding regions.

Finally, there comes a time when section of the spinothalamic tracts is of no avail: the devil has moved upstairs and is reverberating there. Here we are confronted with new difficulties, for lesions dissociate aspects of pain, which, to the normal man, seems an elementary sensation. As the spinothalamic tract passes through the midbrain, fibers leave its main stream, and passing medially, terminate among the cells lying between the periaqueductal grey matter and the deepest layer of the superior colliculus. Mid-brain tractotomy at the level of the inferior colliculus prevents all pain and suffering; whereas, at the level of the superior colliculus, although the sensation of pain disappears, the suffering is as great as ever. In such a man, I am told that noxious stimuli produce suffering, fainting, sweating, and pupillary dilatation as if nothing had been done to interrupt their paths. The ascending spinothalamic tracts play into appropriate portions of the thalamic nuclei, whence relays extend into the cortex devoted to corresponding portions of the body. What is most important here is that in some cases of causalgia and of painful phantom limb, stimulation of the proper part of the postcentral convolution is sometimes perceived as pain. Among these cases are the few who seem to profit by excision of that part of the cortex. It seems unlikely that this cortex is part of a closed path through which the demon rings his changes. More probably, the improvement in these patients resembles the one achieved by peripheral block, and the cortical area in question only contributes to the sustaining excitation.

Finally, lobotomy, which has removed neither the sensation nor the primary affective component in any case that I have seen, does prevent the agony of worrying that makes distress a part and parcel of the typical character of such a patient. Only in this sense does the causalgia matter less to him, that he minds it only when he feels it. It may well be the demon haunts these cerebral paths, but they are certainly the last place where we ought to try to break his circle. I strongly suspect we shall find his last retreat in a certain small region of old and ill-defined structures near the core of the neuraxis, that stretch through the mid-brain and the thalamus. For lesions here affect the very springs of caring and of mattering. With this region left intact after all in front is gone, animals still learn, to the extent to which, without a cortex they can have ideas and control their movements. Whereas, with large lesions here, all else intact, they bother little if at all to respond, and do not learn.

Let us consider the demon from a slightly different point of view. Gasser's diagram represents the normal condition also, as long as we take the circuit K to be degenerative. In that case a certain fraction, smaller than unity of the afferents in II is fed back to them by K and subtracted ; this process keeps up until the circuit has come to rest at a definite level of activity directly proportional to the original input from II, if less variable than it. This level of activity is transmitted upward from x to communicate the sensory information from II; similarly from I by way of y. In causalgia, where K is regenerative, any input from II is amplified and added to itself, not subtracted. The level of activity in K then grows geometrically, until it is bearing all the activity it can bear; in this state it remains, to decline very slowly by attrition of fatigue. No matter how small the primary input, as long as there is any, the output is always the same: the maximum possible at x. The same thing happens if it was a collateral input, say from /, that triggered K. Furthermore, the proper response y from I will usually be prevented, either by Gasser's effect, already described, or else by direct inhibition from x when the latter is greatly excited. In the affected part the causalgic cannot distinguish among heat, touch, and pain, nor can he tell a greater degree of one of them from a lesser: in every case he experiences only the maximum of burning pain.

In this way the demon, causalgia, suppresses practically all the information formerly transmitted over II and every other circuit even partly connected with it. He does it by a kind of imperialism, substituting his own characteristic, repetitive, stereotyped, impertinent response for a whole range of infinitely varied and subtly adaptive responses to the actual facts of the situation. As we have seen, he takes time to get himself ingrained, like a skilled act. Thereafter he moves in on us, no longer requiring for his maintenance the particular structures from which he sprang.

These properties together describe more exactly what Lawrence Kubie has called the ‘repetitive core’ of every psychoneurosis. The difference is that the latter begins elsewhere, in the appetitive circuits.

In common with other psycho-analysts, Kubie makes a sharp distinction between processes which are conscious, and others which were or might have been conscious, but are now shut out of consciousness. In the latter he puts the core of the neurosis. Now the psycho-analytical use of the term unconscious, if somewhat indefinite, is quite a special one. In essence, I believe, it is nothing but the suppression of information as we have just described it. The memories and learned reactions subserved by circuits connected with the regenerative circuit can no longer be evoked, not because anything has happened to them, but simply because all the stimuli which once evoked them, feeding secondarily into the regenerative circuit, now produce only the invariable neurotic response, which displaces all the others. In effect, such memories and such learning become inaccessible, although they return as soon as the circuit ceases to regenerate. The process looks like an active repression, particularly when combined with the secondary effect the psycho-analyst calls resistance. A man usually finds the output of the regenerative circuit disagreeable, so he learns to avoid stimuli which feed into the circuit in any way, as well as situations where such stimuli are probable. Thus the causalgic guards his hand even from his doctor. This development may go extraordinarily far.

But in some respects the psycho-analyst's metaphor is misleading. We cannot say the neurosis, or its root, is ‘walled off’ from the rest of the organism - quite the reverse. The regenerative circuit pours its output into other structures very strongly and usually distressingly. Again, it is only too easy for impulses from elsewhere to trigger the circuit and produce its characteristic maximal output. But that is all they can do: they cannot make it do anything different, they cannot stop it once it has started. We may say the neurosis is autonomous, almost completely so; it is not isolated.

So far I have spoken of the invasion of demons. But they can go outward and overwork a reflex path until its effectors or receptors are distorted or destroyed, as in pruritus ani and in gastric ulcer. I shall give you a different example because my knowledge of it is first hand. Franz Alexander became interested in a group of erstwhile energetic people whose living is crystallized about some goal made unattainable by F ate. Thereafter they do their daily chores without zest. They are always tired. A few hours after eating they feel faint, warm, and sweaty. They eat too much and sleep too much and turn their food to fat. When Alexander came to me, he and his friends, following Szondi and Laz, had studied the glucose-tolerance curves of these people and found them abnormally low. What he asked me was whether these patients suffered from an under-activity of the sympathetic system or an over-activity of the parasympathetic system or both, for he knew that atropinizing the patient prevents the weariness and the postprandial faintness, although it does not restore the zest. For this reason he names the condition ‘vegetative retreat'. So far our studies of their sympathetic system are far from complete; but of an excessive vagal excitement of the pancreas there can be little doubt.

Reliable statistics have shown us that neurotic patients are significantly more sensitive to insulin than is normal for their age and diet. Not so Alexander's patients. In their cases, to account for the increased speed of removal of sugar from the blood and the abnormal smallness of the final values after they receive sugar by vein, one must suppose an excessive secretion of insulin caused by excessive vagal excitation of the islands of Langerhans. Thanks to DeWitt Stetten, there is an easy way to check this; for he showed that with an excess of insulin, water made with heavy hydrogen, given concurrently with glucose, left heavy hydrogen in the fatty acids that are then produced because the patients turn their foods to fat. The odds are many to one that, on receipt of sugar, though their body temperature remains constant, their uptake of oxygen declines by an amount proportional to the amount taken from the sugar as it goes to fatty acid. If all of the sugar we injected went that way, we might expect a fall of 50% in oxygen uptake while the sugar was disappearing from the blood. In these patients we encountered falls as great as 30%, meaning 3/5 of the sugar went that way; in a normal man there is no change.

Let me rehearse, then, the doings of this devil. Springing from the tedium of life, he has produced an exaggeration of anabolic processes to a degree which has actually enfeebled his host and only fatigued him the more, thereby preventing him from developing a luxury of energy sufficient to extricate himself from his intolerable plight.

At this point I ought to hold my peace where I would in all conscience admit my failure and cry for help. For years I have tried and failed to find out how the brain knows how much sugar is in the blood; all I can be sure of is that it tastes it in some place other than the brain, for I can fool it. For years I have been trying to find all the ways by which the brain affects that quantity, but one eludes me. For the brain can still control blood sugar when the pituitary is removed, the vagi cut, the spinal cord transected above the topmost outflow of the sympathetic system. So much for my incompetence.

Causalgia exemplifies two modes of transition from an inverse feedback to a regenerative action. It begins by an injury which is equivalent to throwing a switch that reverses the sign of the feedback from negative to positive. Its ingression into the spinal cord is equivalent to a change in the ratio of output to input, or gain, of an amplifier, which overloads it. This change in gain is obviously the result of oft- repeated over-activity in the circuit. Now, in general, gain depends upon frequency. For a circuit whose action is inverse at the frequencies it is intended to handle, there will exist certain other frequencies, higher and lower, for which it is resonant. To be alerted to anything is to increase the gain in some circuit. If this circuit is excited at a frequency for which it is resonant, great overactivity can be produced, and like causalgia in the cord, may permanently augment its gain, so that it goes into selfsustained activity.

Telephone switchboard operators used to be subjected to a signal alerting them to plug in a line, ask and hear a number, make a connection, and listen until they hear both parties speak, cut themselves out of the circuit, and stand by to receive the next alerting signal. Lively girls of high intelligence, doing this at busy switchboards, became tense or nervous, had rapid hearts, sweaty hands, and nightmares. This form of nervous breakdown became a serious industrial hazard, requiring months of care in a sanitorium. The expense to the company was great enough to prompt the development of the dial system.

This genesis of neuroses has been studied thoroughly in sheep and goats by Liddell. These beasts respond by lifting the fore-paw to a barely perceptible electrical shock. If the stimulus is repeated at equal intervals of one or several minutes, the sheep soon gives the response at the proper time, even if a single stimulus is omitted. That is all that happens. If he is taught that the beat of a metronome at one per second is followed by the shock, he tilts and raises his head and pricks up his ears whenever he hears the click, and may even raise his leg before the shock arrives. He can be taught to respond similarly to touch or sight instead of sound as the alerting signal. This is neither a painful nor a distressing experiment, nor one in which there is any task to require a difficult discrimination. Nevertheless, if the signal and shock are repeated at intervals of one minute or of four minutes, the beast becomes neurotic. With the shorter interval, he stiffens the fore-limb, breathes slowly, has a slow pulse and somewhat narrower pupils. With the longer interval, he begins to shake or paw with his fore-limb, pants, has a fast pulse and dilated pupils. Once firmly established, by a few runs each day for a few weeks, the reaction becomes so fixed that it lasts at least five years without reinforcement. Moreover, the beast ceases to be normally gregarious, and his fast irregular heart and respirations and much moving about continue permanently, even during sleep. Obviously the frequency of stimulation determines not only the existence of the neurosis, but also whether the sympathetic or parasympathetic system is the one involved.

Beside the neuroses that are generated by repetitive experience, there are some which clearly spring from a single, intense psychological insult. I have in mind what the American Army calls ‘Blast'. A man near an explosion, but not so near as to suffer organic damage to his brain, starts to run in frenzy. After being stopped, say long enough to smoke a cigarette, he has lost all memory of the events from just before the blast until he smoked the cigarette. Thereafter he is startled easily, is terrified by the sound of airplanes or the back-fire of a passing car, and dreams of battle frighten him. He comes to resemble a hound gone gun-shy. From Walker's work we know that acceleration of head as great as in these patients produces throughout the central nervous system, an electrical disturbance which resembles that recorded in an epileptic fit. The blast itself can never be recalled. Again, the neurosis is an active reverberation, as shown in the autonomic outflow and the dreams. Why a single blast is able to set up such a process is not obvious. One would naturally suspect that the applied force, rather than the host of simultaneous signals over many nerves, was the cause, except that similar pictures appear in men too far removed from the explosion; merely as a consequence of seeing and hearing their companions killed in battle. Things of these kinds have easy access to a kind of memory other than either of those apparent in causalgics, neither mere reverberation nor the one that mediates our oft-repeated acts, but the one that stores our glimpses of the world, making it seem like a pack of photographs of things that happened once. Here each attempt to look again at these horrors, or anything that might incite him to revive them brings back the frenzied fear. The content of these snapshots is not itself the fear, and if the fear could be forestalled, they could be seen for what they are.

I do not know when first man had it in his power by drugs to quiet these churning fears. In our Civil War, the patients were made drunk, and, as they sobered, were allowed to relive and discuss the things that racked them most. But we forgot the art of treating them, and re-discovered it in our war with Spain, when it was christened Hypnotic Therapeutics. In World War I we learned it once again, this time with ether, and in World War II barbiturates came into vogue, under the name of Narcoanalysis or Narcosynthesis. Next time, if there must be a next, I hope we have the grace to acknowledge the good works of our forebears, and have the skill to stand upon their shoulders.

To my mind, Fabing's trick2 of following amytal by coramine seems an improvement, at least statistically in its results, and scientifically, for, inasmuch as the bulk of his patients lost their terrors and their amnesia without analysis, synthesis or intentional suggestion by any fellow man, his success ought to be attributed to the sequential action of these chemical agents on the central nervous system. The amytal brought many processes to rest; a violent reliving of the accident ensued, and this was suddenly converted to the waking state by the generalized excitation of the brain by coramine. Fear was swamped out by nortnal activities, among which were the memories themselves of the accident, now quite innocuous.

For all our hypotheses, of the majority of neuroses that begin in civil life, the origin seems to me undiscovered - probably undiscoverable. But the history of any case suggests that early in the process they may be broken up as easily as if they depended for their existence upon little more than mere reverberation, and only later became so fixed as to start up again once they are stopped.

Another origin of neuroses is instanced by conditions in which the gain is increased by the sudden withdrawal of various things, usually narcotic or soporific to the nervous system. I do not mean the convulsion that not infrequently follows the withdrawal of barbiturates. I am thinking, first, of the jitters of the alcoholic who tries to stop, and becomes unable in his tremor and terror to lift a glass to his mouth; second, of the violent autonomic discharge that ensues when morphine is withheld from those physiologically addicted, including the decorticated dog; and last, that all-pervading anxiety which comes when we lose the most wholesome of soporifics, a convivial bed-fellow. Fortunately, thanks to your British drug, myanesin, these problems have become simply and safely manageable. Henneman in our laboratory has most elegantly demonstrated that myanesin will prevent the activity of intemuncials necessary for multisynaptic arcs, including the nociceptive flexion reflexes and the facilitation and inhibition produced by direct stimulation of the reticular formation of the mid-brain and hind-brain or by torsion of the head on the trunk. It was these experiments which led Dr. Cooke to suggest trying it against the overactivity of masses of small cells produced in the aforesaid withdrawals, and so to experiments at Manteno State Hospital on large numbers of patients with sympathetic symptoms.

I have purposely dodged the term ‘anxiety'; for it is now applied to any state of the central nervous system giving excessive sympathetic activity. I have already described three such states, which are clinically and experimentally distinct: the first induced by repetition in telephone operators and in sheep, the second by single fright in a blasted man and gun-shy dog, the third by withdrawal of certain drugs in man and dog. All three conditions show exaggerated startle, and respond, at least temporarily, to myanesin. A good instance is my old dog Puck, who was early frightened by fireworks. Every thunderstorm puts Puck into a state of terror: he shivers continuously, hides under the bed, and refuses food for many days. The slightest stimulus startles him. Myanesin will not prevent thunderclaps from frightening him, nor does it completely suppress the startle; but after the storm passes he eats, and instead of hiding, comes to be petted without shivering. Myanesin has evidently damped the regenerative process. In the remaining case of the sheep, experiments with myanesin are now under way, although we do not yet know the results.

Besides all these, there is a fourth condition like the apprehension felt by a man about to visit the dentist, except that it often wants any well-defined object. The sympathetic system is evidently overactive, but mere noise will not augment its output further. The man shows no great exaggeration of startle, and his feelings are not much affected by myanesin, although his sympathetic output may decline a little. Masserman's cats appear to furnish the corresponding condition in animals. They are put into the ordinary experimental set-up for conditioning, where they learn to perform some response rewarded by food. Thereafter, when they perform the response, they receive instead of the food, or accompanying it, a blast of air in the face, like a cat spitting. Such cats will not eat, fight against being put into the conditioning box, and become unsociable. But they have no exaggerated response to startle, do not increase their sympathetic activity in response to noise, and, as I have just heard, are not measurably affected by myanesin. They seem anxious - but I suspect their apprehension is more like that of the ordinary neurotic patient.

Every treatment of causalgia has its counterpart in handling neuroses in general, at the proper stage. But, at the moment I am chiefly interested in one resembling the newest treatment of blast. We have had nearly five years’ experience with it to date. Of the first 117 whose treatment ended some four years ago, 79 are still well today, and 2 who relapsed have recovered on repetition of the treatment.

For its rationale let me recall to you Gasser's diagram when the circuit K is regenerative. If we raise the threshold of b, we shall be able to halt the reverberation temporarily. When the threshold falls again, the normal input / may be able to pre-empt the necessary common internuncial, so II will not get going as before. Whether this happens depends upon the exact times at which signals from I and II arrive. A second way of doing this would be to make b temporarily indefatigable; for then I could fire it at any time and be on an equal footing with II in the race for possession of b at every round. A third possibility lies in the background of excitation and inhibition, not indicated in the diagram, but always there in the living nervous system. For, any shift that might fail to excite II or inhibit it or do the reverse to I might upset the balance. In fact, merely to excite both maximally or inhibit both maximally would tend to equalize their chances for possession of b.

Lorente de Nó has shown that CO2 raises the voltage and threshold of all axons, and also, what may be most important here, it renders them almost indefatigable. The effect of this on the activity of various structures is diverse. The cortex, normally so far from fatigue as to be capable of an epileptic discharge whenever it is electrically excited, has its normal level of activity controlled by inverse feedbacks which keep its afferent impulses down to a small established average. Consequently, the effect of CO2 on fatigability is here without effect, but the rise in threshold it induces puts a stop to cortical activity. In the respiratory mechanism the opposite is true, for its fatigued neurons are always the recipient of more impulses than they can relay. They are too tired to have a convulsion, no matter how frequently we excite them electrically. CO2, by raising the threshold, can make little difference, but because it also prevents fatigue, it will cause a vast increase in respiration. Other structures of the thalamus, mid-brain, and hind-brain exhibit intermediate conditions.

Whether this is the complete story, or whether there is also a chemical specificity, remains to be proved. At the moment, we can only add that respiration of 15% CO2 in O2 prevents the seizures normally induced cortically by electrical stimulation or by metrazol or similar substances, whereas it augments the effect of bis-beta-chlor- nitrogen mustards, which start fits in the hind-brain, notable in the cerebellum. It follows that the respiration of 30% CO2 in O2 will alter, briefly but extremely, the background of excitation for neurotic reverberant feedback loops, and for normal

inverse ones. This alteration may halt reverberation. Over and above this shift, by rendering b indefatigable, CO2 gives I and II equal chances for the necessary internuncial; in some of them I will succeed.

In giving, say forty treatments of say forty respirations .each, of 30 % CO2 in O2 one cannot avoid the suggestive effect of a doctor, a nurse, a mask, and submission to transient loss of consciousness. Still, in view of our contagious incredulity, particularly in the first series, the score is too high to attribute to psychological factors. Others now have longer series and better scores than we. In fact, their enthusiasm is somewhat alarming - particularly their reported success in treating gastric ulcer. I have been most surprised by the results in disorders of speech, commencing in childhood and treated in the twenties or late teens. If we exclude stutterers - the people who say I did — I did — I did — etc., who often have additional signs of damage to the brain, such as an arm that fails to swing normally in walking, or too fixed a stare - and accept only stammerers - those who say I -------- I did it - then, of 50 cases the successes numbered more than 25. Having seen my sister, a teacher, and my cousin, a surgeon, bring on stammering by learning the one to write, the other to shave with the left hand, I am not altogether satisfied with supposititious psychic skeletons in the unconscious. It is enough to know that the devil is a reverberation who succumbs to CO2

Unfortunately causalgia and great anxiety are prepotent demons. Under CO2 they are intensified, as if fatigue alone had limited their sway. The patient never leaves the doctor long in doubt on this score. He simply refuses a second or third treatment.

Beside prepotent demons, there is another condition that resists - or is unaffected by — CO2. I hesitate to speak of anankastics - obsessive or compulsive - again at this meeting. The only experiments that have produced a condition which may be compulsive are Kurt Richter's on rats, poisoned once severely and thereafter required to select their diet from samples of various foodstuffs, of which, now one now another contained a little of the odorous poison. They hang on to the wires of their cages, wrap their tails around a wire and, even in sleep, hang on as if this would insure their not eating the poison in a moment of relaxation. This behavior persists for at least sixty days when the poison is withheld. If a similar picture can be produced in primates, we may be able to work out the complete circuit. In man mayhem must be less radical, but obviously there has been enough of it already to show that some portions of the fore-brain contribute to or constitute the closed path, or reiterative core, of obsessional stereotopy. I only hope that while neurosurgeons still have the operations on their consciences, psychologists will have an opportunity to study the way leucotomy, topectomy, and thalamotomy destroy the force, and finally the ideas, of those troublesome sentiments, for until we know more than we do today of the nature and boundaries of the consequent psychopathy we are in danger of robbing the patient of some of the ends of life which make it in the long run socially worth while.

Discussion

The Chairman, Professor F. L. Golla, said that there was one point which struck him and that was whether a mechanistic approach to the neuroses was a possibility. Somewhere about 11 o'clock at night, standing in one of the highways, one would see a lot of people passing along in a great variety of moods; it was the hour at which the public houses closed. He could not think that very much would be learned from the sight of the effects of the poison but from the fact that each had a different system, a different stratum at which the alcohol worked. Professor McCulloch might be asking too much, it might be that they would ultimately have to correlate the mechanistic account with introspection to make it intelligible. As living beings they could do something which no mechanical thing could ever do - they could objectify themselves.

Dr Derek Richter wished to pay a tribute to the most erudite and stimulating account which Professor McCulloch had given. Professor McCulloch had described, particularly in his writings and to some extent in his Address, the electrical mechanisms . in the brain, and he would like to ask if there was any recent evidence of an inter- Telaiion of the electrical rhythms of the brain and behavior at the higher levels. The previous work by Adrian and the work done in the Burden Institute were a little disappointing in that they showed a negative rather than a positive relationship between the electrical rhythms which one could pick up and actual behavior. It was known that the alpha rhythm disappeared if conscious behavior was started. They had been particularly interested in that problem at Cardiff and had recently been working on the relations between the actual phase of the electrical rhythms and behavior. Some of the evidence might appear to give confirmation of the views of Professor McCulloch. The actual effect which he wished to mention was the relation of the phase of the alpha rhythm and the moment of initiation of a voluntary movement. The alpha rhythm could be shown very easily in an individual who was sitting relaxed with closed eyes, and the moment when he initiated any voluntary movement appeared to bear a relation to the phase of his alpha rhythm. Every tenth of a second the probability of his starting a movement increased, showing, in effect, a working relation between one of the rhythms and psychomotor behavior(1).

Was there any other evidence which would point to an active relationship between the rhythms rather than the negative type of relationship which had generally been described?

Dr. Denis Hill thanked Professor McCulloch for a most interesting Address covering so many fields in which they were all concerned. He was surprised to hear him use the word 'demon’ in describing the development of neuroses. He referred to reverberating processes of activity which might move towards the cortex and he referred to the state for such reverberating activity as the demon: ‘the demon moves'. Keeping to his mechanical terminology it seemed to the speaker that Professor McCulloch was suggesting that the attention of the rest of the brain was directed towards the movement and activity of this electrical ‘demon'. If that was so, there was a lot left after the reverberating circuit was accounted for.

Dr. D. A. Pond (London) said with reference to the idea of feedback, it was clear from Professor McCulloch's talk how nerve injury could produce ‘cross-talk’ and positive feedback in cases of causalgia. However, it was not clear what was the analogous explanation for the development of positive feedback mechanisms in the C.N.S., where there was no evidence of structural damage. The concepts of circular reflexes, the laying down of new pathways, etc., had a long history in psychology and physiology, and he was not clear how far Professor McCulloch's description of positive feedback as a functional disturbance in an electronic machine, threw light on what were the possibly comparable disturbances in the nervous system in cases of mental disorder.

Dr. F. A. Pickworth (Birmingham) had studied the nature of nervous processes in mental disorders, and in this had profited much by reading Professor McCulloch's publications.

He (Dr Pickworth) wished to distinguish between mental and neurological processes. As far as the mind was concerned there was plenty of evidence that the central nervous system was not the ‘master tissue’ of the body. For example, the brains of schizophrenics were in his experience often better structurally than those from non-mental cases. Schizophrenics could be taken as typical since they occupied half the mental hospital beds throughout the world. Freeman (2) applied the terms ‘particularly normal' to such brains. Dr. Pickworth had known intimately several persons whose minds and personalities were not grossly altered by large cerebral destructive lesions. He had seen in Institutions, quadriplegic idiots who had minds and even characters of their own, although handicapped in the development and expression of them. Cerebral stimulation can restore function in long-standing mental abeyance, which fact establishes the integrity of the subservient central nervous system. The conditioned reflex, contrary to general acceptance, was not typical of a mental emotional state, since so much automatic (robot-like) behavior was devoid of mental-emotional component. Attempts to identify unity of mind with the paired structures of the central nervous system were therefore doomed to failure. By contrast, all intense mental-emotional processes were regularly accompanied by vascular changes in the body. Corresponding mental changes were to be noted with physiological changes of blood pressure, which altered the local cerebral blood flow. Similar changes of both could be induced with drugs, toxins, or hormones acting over a period of time. He had been able to show, by a specially devised staining technique, structural alterations of the cerebral blood flow in cases of mental disorders. These changes were very evident in early general paralysis. The lantern slide shown indicated clearly congestion and gross structural lesions of the cerebral blood vessels of the motor cortex. He believed that, if cerebrovascular lesions were accepted as the pathogenesis of general paralysis, one could apply Osier's dictum of ‘know syphilis in all its manifestations and all things clinical shall be added unto you', to other mental diseases, including the psychoneuroses. The aetiological agent may differ, but the pathogenesis is the same, namely pathological deviations of the local cerebral vascular flow, details of which are given in a pending publication (3), The dependence of reflex nerve function upon the local blood flow was first shown by Sir F. W. Mott (4). The blood flow abnormalities in schizophrenia have been likened to ergot poisoning. Those in early and late encephalitis are readily demonstrable, and in his opinion easily correlated with the sleep disturbances and mental symptoms. The literature contained most of the facts necessary, when read from the above aspect, to enable us to make drastic changes in our conception and treatment of mental disorders, and to acquire a better understanding of the mind itself.

Professor McCulloch, in reply, said that he left his research, in problems raised by Organic Neurology while he was at Bellevue Hospital, for less than two years which he had spent in Psychiatry at Rockland State Hospital and from it returned to the laboratory with enough problems to keep him busy for the rest of his life. What he had done in his lecture was to rehearse the classical problems of neuroses, outlining for each neurosis the corresponding experimentation in animals in so far as he knew how to do it. It was his hope that some of his audience would begin to be interested in what one could do with a patient who could not confuse the doctor by his vocabulary.

He took up the questions in the order they were asked. The first concerned the mechanistic approach to the problem of neurosis or of any other psychological activity. One often heard that this or that property of the nervous system could be imitated by machines. Since he had shown that machines can and do have ideas and purposes it did not seem to him to be any great matter to design a machine that objectified itself, which is to have reflective knowledge of its own thinking.

Next, in answer to Dr Richter, who had asked concerning new evidence of resonant circuits, notably the relation of the Alpha activity of the brain to the output by mouth,

or by hand and to perceptions. The man, Craik, who held most promise for the world in this direction unfortunately was dead and his work was so buried in Governmental reports that except for his little book it was not accessible. Among his most brilliant work were certain observations of the times during which man took in that amount of information on which he based a predicting response. Craik showed that in some cases it took 2/10ths second, and in others 3/10ths second with a rather sharp break between them, and thereafter the man took in no information during the next l/10th second. John Stroud, now working with the U.S. Navy, had followed this same line. He showed that man perceived in moments of about I /10th second each, lacking internal temporal structure and movement, and Stroud was correlating these moments with the electro-encephalographic records. He had shown that these 1 /10th second visual moments could be locked in by auditory activity. Anyone who worked with the cathode ray oscilloscope trying to hold a pip in the center of the screen and put the click of the fly-back to his ears by earphones, and turned the frequency to a convenient setting found that he set to his own alpha frequency. The evidence on this was just beginning to come in. There was but one thing he would like to persuade his audience to do namely to collect Craik's work and get it published soon.

With regard to the demons: a demon is not a structure, a demon or a gremlin is but a circuit-action. It is in almost all cases regenerative circuit-action which should be a kind of servomechanism - inverse or negative feedback. It was the peculiar property of complicated circuits like the nervous system that one usually could not precisely locate gremlins in them. Certainly the gremlin is never in a single item without a circuit but always in a closed path. What he had tried to point out was that this gremlin, this resonance, could begin in a disturbed reflex and, if it lived long enough, it modified some other loop and so could give birth to a second demon; whereafter the first demon could die, but, as far as his character or his soul is concerned, receives the same gremlin. He was not sure whether the difficulty the questioner had had was that the lecture attributed mental properties to gremlins who certainly have ideas and intentions.

To Dr. Pond's question as to cross-talk and what turns up the gain, the answer was that the cross-talk in a causalgic nerve made it act repetitively and repetitive activity if persistent in someway, turned up the gain of the circuits in the cord. So when we learn to skip or to play a piano, erstwhile inadequate stimuli become adequate though we do not know how repetition turns up the gain. It is difficult to imagine how this happens in the spinal cord where one would expect all connections to be firmly established by the time one can walk. Yet it seemed now clear that new pathways might be formed or old ones lost under unusual circumstances. This was first reported by Coller and Shurrager, but an excellent neurosurgeon, A. A. Ward, and a psychologist, Donald Marquis, were unable to teach the spinal cord. This suggested to Dr. Lettvin that the difference might lie in rough handling, destroying some paths afferent to the motoneuron, thereby leaving it accessible to other impulses. Lettvin, therefore, cut the dorsal roots of a two neuron reflex arc, stimulated affe-rents normally inhibitory to this arc and simultaneously stimulated antidromically the motoneurons of this two neuron arc. Thereafter the erstwhile inhibitory affe-rents excited the motoneurons. The reason this work has not been published yet is that we do not know the histologic details nor are we certain the new path is monosynaptic. In any case it shows that the behavior of the cord can be modified so that formerly inadequate stimuli become adequate. This is one kind of memory. The changes that occur higher in the nervous system may all be due to the kind of memory which preserves snapshots of the world to be re-evoked whenever this is required.

The last question was a crucial one. He did not join in the discussion that morning when Gellhorn lectured although he had wanted to cry ‘hear, hear’ because Gellhorn was on the right track. He thought neuropsychiatrists had habitually looked to the cortex for things actually in the brain-stem. Gellhorn was persuading them to look in the right direction. However, the brain-stem was not necessarily the master tissue of the body because there is no one master tissue. Meduna's work had shown that about two-thirds of so-called schizophrenics were biochemically abnormal, being unable to handle glucose properly when given it by vein, and unable to convert levulose into glucose, having something in the blood rendering them resistant to insulin, and putting out in their urine a substance that raised blood sugar in animals. About 1 mg. of this material when purified doubles the blood sugar of a 250-gramme rat. In these disorders of the brain we are dealing with a biochemical disorder which is almost as obscure as diabetes mellitus was when Professor McCulloch was in medical school.

Footnotes

Reference

Kibbler, G. O., Boreham, J. L., and Richter, D. (1949) Nature, 164**,371; Reports of 2nd Internat. Congress of EEG (1949). Paris.

Freeman, W. (1933) Neuropathology, p. 256. Philadelphia and London.

Pickworth, F. A. (1950) New Outlook on Mental Diseases. Bristol.

Morr, F. W. (1900) The Degeneration of the Neurone, p. 50. Croonian Lecture, London.