A drawing emerges:

The drawing as a complex adaptive system

Simon Downs

Loughborough University, ENG

It is in the visualization of ideas, and the expression or representation of our ideas, that we can bring something more clearly into consciousness. A drawing might be seen as an externalization of a concept or idea. (Brooks, 2009: 319)

Most such sketches should be classified as 'drawings' which are representations of either direct percepts, or ideas and images held in the mind. (Goldschmidt, 1991: 1)

Introduction

Drawing as a practice has been written about for centuries. Drawing as an outward expression of internal thought and culture has become a formal subject of research in the last half-century and the quotes above express a view that is commonly held in the drawing community as an experiential model for the act of drawing. This kind of internalized model of drawing, a direct transcription of thought to paper1, fails to address key questions about the construction of a drawing and of that drawing’s ability to communicate to both author and audience. A state of affairs that this paper proposes can be usefully addressed through treating drawing—both verb and noun—as an emergent effect of a complex adaptive system.

This paper proposes that there are tangible benefits for the drawing community in introducing an understanding of complex systems to our canon. The first part of the paper will offer an argument about drawing’s status as a complex system, especially as a model for drawing existing canonical but discrete positions into a functional whole. The second part of the paper describes the characteristics of drawing (in its verb form) being a complex adaptive system while drawing (as a noun) has characteristics of an emergent property of the system and lastly offering a drawing specific model for the system.

There will be disagreement from some involved with drawing research. The proposed model doesn’t come from critical theory position (a very popular approach) or from a craft base (a historically durable approach): but it does address the whole experience of drawing, from theory to practice to reception, as a single system: through not treating drawing as a black-box system with the drafter’s2 brain at one end and a completed drawing at the other.

There are observed parts of the drawing process which are difficult to explain in other ways. For example many drafter’s experience drawing as a process where something ‘other’ happening in the process beyond a direct relationship between intent and the physically processing a drawing. The reported experience of drawing is that the results are commonly beyond the initial concept, effective yet substantially different. Research confirms that something other than a direct transcription of a mental state is happening. Riley (2009) demonstrates no direct relationship between a drafter’s internal assessment of the success of their applied practice and audience assessment of the work, Suwa & Twersky (1997) demonstrate that the design drawing process is a set of games with the victory condition being a success measured by success in addressing the initial brief, but not a rendering of a predefined solution. It is recognized in the field that there is at least some feedback process at play between the drafter, broader culture and the work; modifying drafter intent to meet the objective of the task, sometimes known in the field as ‘Thinking through Drawing’ (Brew, Fava & Kantrowitz, 2011). By the same token Schön (1984) talks about the designer (drafter) having a, "… reflective conversation with his or her idea..." Suwa, Gero and Purcell (2000) write about the discovery of "… unintended visual/spatial features in sketches…" It has been experimentally demonstrated that something consequential and novel is happening through the drawing process.

Common features of the drawing experience are that:

- The final image will be complete (as measured against the initial intent)

- The final image will be functional (as measured against the initial requirements and the cultural frame), but that…

- … the final image will be distinct from either the initial intent or requirements.

This paper takes subject’s (in this case a drafter) expressed belief about their experience (of drawing) as valid data that something ‘other’ has happened in the process of drawing (after Dennett, 2003).

The true work of art is born from the 'artist': a mysterious, enigmatic, and mystical creation. It detaches itself from him, it acquires an autonomous life, becomes a personality, an independent subject, animated with a spiritual breath, the living subject of a real existence of being. (Kandinsky & Max, 1963)

However while the paper is explicitly taking the point of view that this reported ‘mystical creation’ is experientially real for the drafter, it is not suggesting a numinous origin.

The existing drawing literature deals heavily with the experience of drawing (from Vasari, 1906 to Ruskin, 1971), more recently there has been experimental work on the psychological strategies used when drawing to solve problems beyond the drafter’s existing knowledge at the initiation of the drawing process (e.g., Suwa & Tversky, 1997, Goel, 1995; Goldschmidt, 1991, 1994, 2003; Magnani, 2013). There is work dealing with the exploitation and uses of drawings as a socially mediated tool-set (e.g., Lawson, 2004; Schenk, 1991) and there is of course a mountain of work dealing with semantics of the reception of all sorts of visual signification (from Saussure and Peirce to Sebeok and Wheeler), including signification in drawing: through mark or gesture, for example. Connecting these elements by regarding the whole process (from culture to drafter and back to culture) as a system rather than discrete events, this paper proposes that drawing (the activity) is a Complex Adaptive System that creates an emergent drawing (the artefact).

Drawing: A commonplace miracle

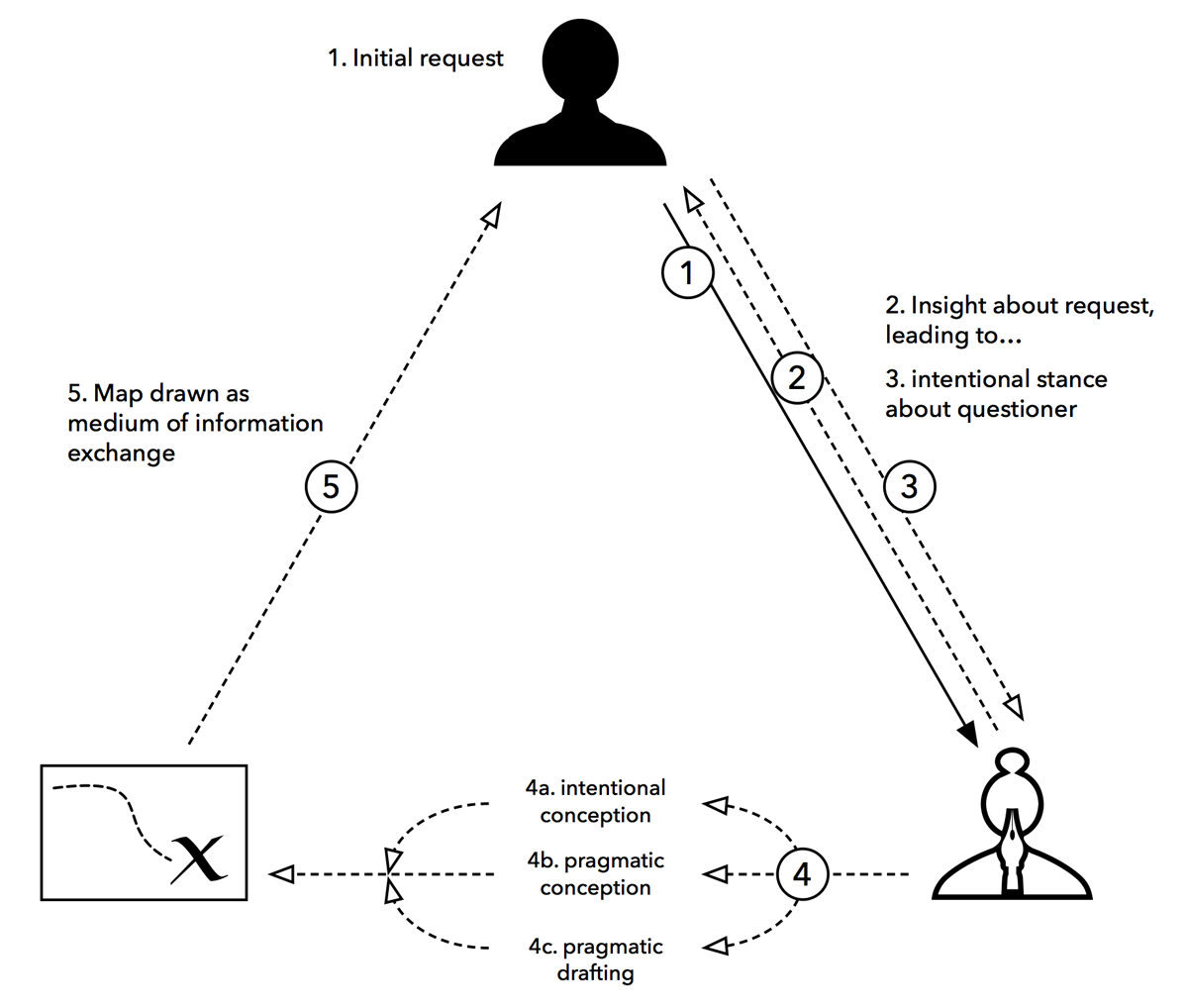

If asked for directions by a stranger we may, on consideration, make the judgement that beyond a certain number of steps verbal or textual directions will simply cause more problems than they solve3. In such circumstances an impromptu map offers a solution. A scrap of paper and pencil allow us to work up an impromptu schematic of the locality, with significant directions for the questioner. Which, in turn, allows us to direct the them to their destination, speedily and without fuss (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The process of drawing a map for a stranger

Figure 1: The process of drawing a map for a stranger

Please stop for a moment and marvel, because this sketched map represents a commonplace miracle.

Our map, forged from a store of local knowledge, is refined into a schema that is legible for to the questioner.

To do so it is assumed that the intentional stance (Dennett, 1989) that we hold about the questioner and their visual literacy is one that includes some sort of common visual lexicon.

- This common literacy is sub-set of all possible visual literacies (e.g., pragmatic vs semantic), and must be selected in this way to be effective. An intentional feedback loop.

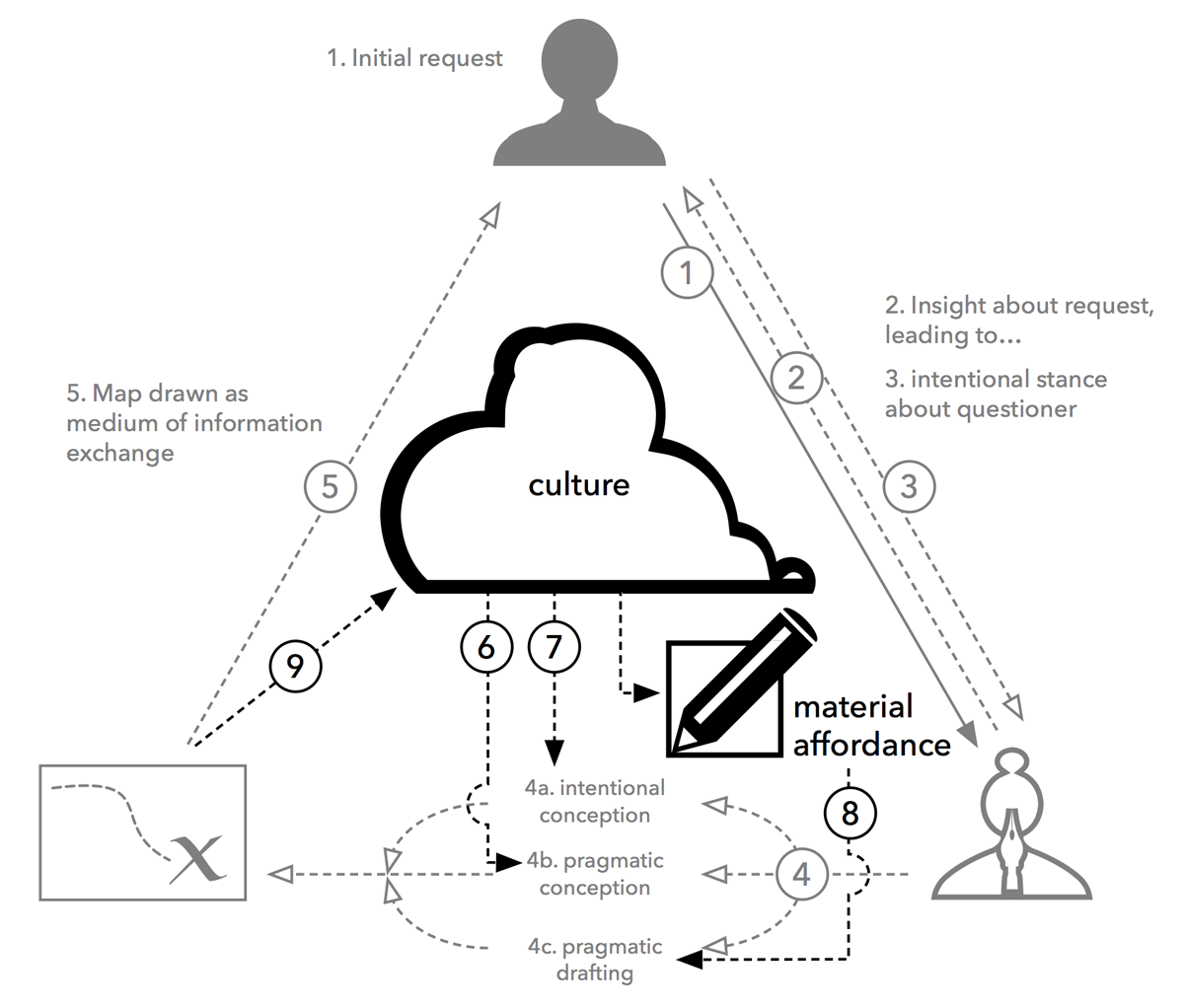

- Too much detail is confusing. The drafter makes a judgement on the details to include. This is, in itself, another intentional feedback loop (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The process of drawing a map for a stranger, with the cultural dimension

The mapping assumes a degree of familiarity with the arrangement of drawn objects (in both parties) that allows for the creation of this pragmatic communication, held in common between parties. More feedback loops.

- A pair of lines in parallel isn’t a universal icon for a street.

- A pair of lines in parallel, but at right angles to the first pair isn’t a natural sign for a side street.

- An arrow hasn’t always indicated direction (see Figure 2).

The final map is the drafter’s local knowledge recoded for a stranger's mind. If we assume these are discrete processes, the accidental combination of cultural knowledge, intentional stance, common visual languages and drawing literacy looks quite unlikely. Yet it happens all the time.

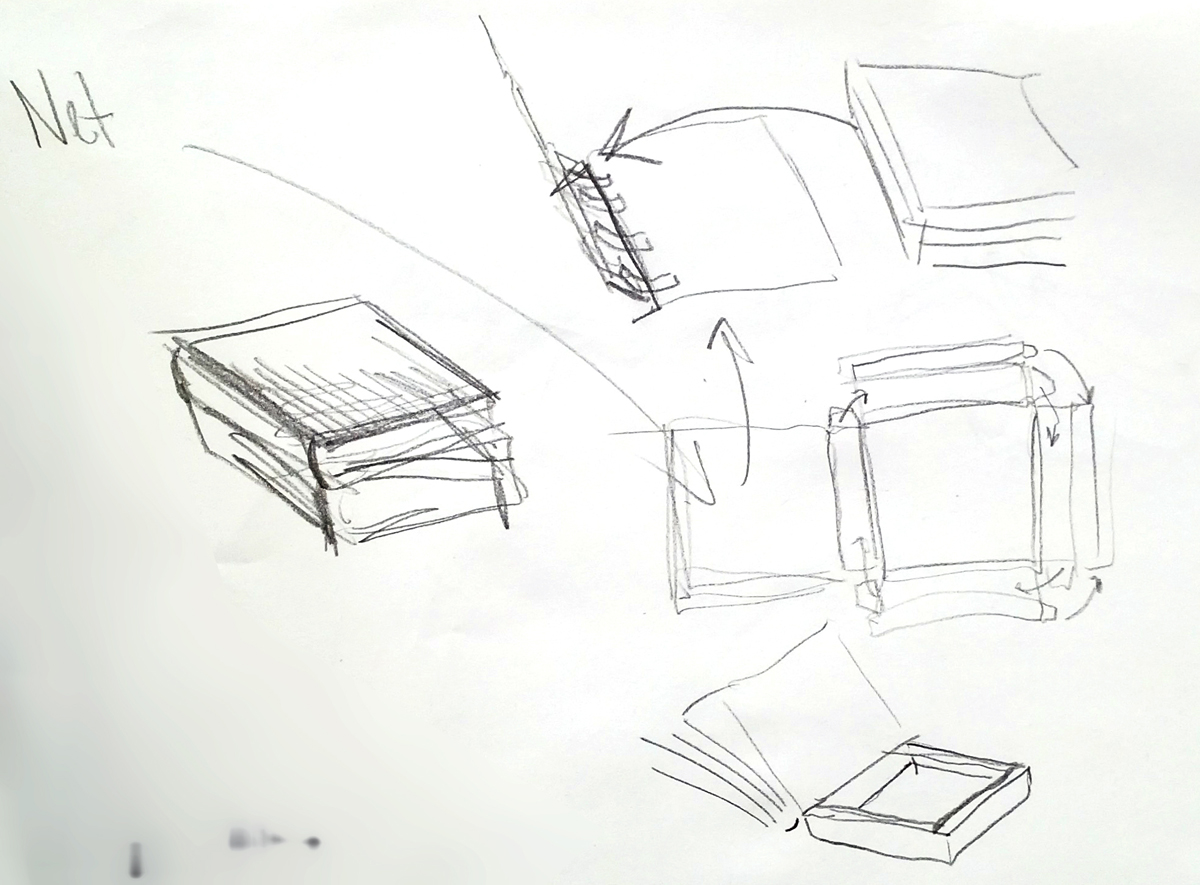

This use of drawing as an exchange medium between co-workers is established practice, not just in the ‘creative fields’, but in surgery, mathematics, biology, the military and many other fields (see Figure 3).

Many individual elements of this process of drawing to communicate are canonical in the drawing literature. The cycle of ideation, drawing, and evaluation as the drafter works (Goldschmidt, 1991, 1994, 2003; Suwa & Tversky, 1997). Drawing as a communications device in: design (Ishii et al., 1992), in education (Hall, 2008), medicine (Rollins, 2005). Dennett's Intentional Stance (1989) offers a viable way of describing the way in which we fixed on an apposite symbol set for this notional stranger to understand the route (see Figure 3). Norman and Baynes (2013) give us a model that describes the process of articulating a drawing to enable design evaluation. The discrete operations of drawing have been well served.

Figure 3: An example of a sketch describing a technical process

What is missing is a description that connects these varied, but canonical, parts in a way that acknowledges the existing models but frames them within a broader whole, with each part as valid and functional contributor to the total. Such a framework is provided by Complexity Theory, with the drawing being the Emergent product of the system.

Complexity allows for a model of drawing that acknowledges a variety of inputs made to an individual drawing on a case by case basis, producing results that can be original and distinct in operation; that is causally effective on the parties involved, that references the past yet demonstrates novelty, while still existing in a framework with cultural relevance.

Why drawing is complex

The world is full of complicated things: most of which don't demonstrate the sort of behaviors that can be characterized as Complexity. We are familiar with agglomerations of elements and events that incorporate a large numbers of functional elements; for example a car; but which in their multitude of parts compose to make systems that are broadly predictable in action. Despite differences in individual elements; for example diesel or petrol, manual or automatic; most drivers can drive most cars (most of the time): the system 'car' is well understood. This is an example of a Complicated System: which is to say a system where the function of the individual parts in the system are known, as is their contribution to the function of the whole.

The philosopher Paul Cilliers (1998) uses the metaphor of a Jumbo jet to help understand a complex system.

If a system—despite the fact that it may consist of a huge number of components—can be given a complete description in terms of its individual constituents, such a system is merely complicated. (Cilliers, 1998)

But the evidence shows that an understanding complicated systems only takes us so far.

Research shows that when agglomerations of elements incorporate large numbers of parts; such as in a drawing; interact with other systems; cultural, mental, biological, practice, physical; with a ‘memory’ (the capability of forming a feedback loop); something ‘other’ happens. Something beyond the sum of its elements. In the case of a drawing, something beyond the original expectation of the drafter.

The kinds of systems that produce this sort of unexpected behavior are labelled, not as 'complicated', but as systems showing 'complexity'. Chan (2001: 1) gives a usefully brief description: "Complexity results from the inter-relationship, inter-action and inter-connectivity of elements within a system and between a system and its environment."

A drawing is composed of known elements that can be described a priori to an atomistic level. But like Cillier's plane it becomes part of a larger system of contributory elements (in the case of the plane: weather, geography, user action, etc.) which, in combination with the known (e.g., plane) start to show Complexity.

In a complex system, on the other hand, the interaction among the constituents of the system, and the interaction between the system and its environment, are of such a nature that the system as a whole cannot be fully understood by simply analyzing its components. (Chan, 2001)

The process of making marks is historically canonical, with the underlying cognitive processes being well described, but we observe that beyond certain numbers of drawn interactions novel characteristics emerge in the drawing. The final drawing mutates beyond the description laid out by the task (e.g., a brief) in ways that have become a central feature in processes like design methods ideation, development and modelling. This mutation is attributable not to the elements themselves, but to the ways in which these elements interact with each other, the drafter, the audience and into the outcomes of these interactions which feed back into the drawing task. Each of these elements has become a dependency of the larger drawn system.

This way of thinking stands in stark contrast to earlier models of thought where (if reductio ad absurdum arguments are applied) larger groups were just compounded of smaller things. Here we might find that understanding the atom allowed you to understand proteins, understanding proteins allows you to understand cells, which in turn allows an understanding of brains, which affords us viable insights into thought, and so on up to the point where the Mona Lisa can be determined as the inevitable outcome of the Big Bang.4

So when, in 1927, Bertrand Russell stated in The Analysis of Matter that, "...the characteristic merit of analysis as practiced in science: (is that) the properties of the complex can be inferred from those of the parts." (Russell, 1992: 22) A proposition that set against contemporary physics must have seemed plausible, while deliberately ignoring interaction and feedback as the basis for subsequent generations of constructs. Russell is cited here because he explicitly wrote against the emergent (e.g., C.D. Broad as quoted in Goldstein, 1999), and explicitly intended the observation to include the cultural. He makes a point about "all articulate symbolic activity" that forms languages, which be assumed to including drawing, possessing a defined atomic structure that defines the limits of possible communication:

It may be that there are facts which do not lend themselves to this very simple schema; if so, they cannot be expressed in language. Our confidence in language is due to the fact that it … shares the structure of the physical world, and therefore can express that structure. But if there be a world which is not physical, or not in space-time, it may have a structure which we can never hope to express or know. Perhaps that is why we know so much about physics and so little about anything else. (Goel, 1995)

Goel, in his Sketches of Thought, goes on to counter Russell’s argument:

The distinguished company notwithstanding, the implication of this line of thought is that thoughts/contents that can not be embodied in a language with such properties are unthinkable. This position relegates all human symbolic activity that lacks these properties to the “emotive cries of animals.” (Goel, 1995)

Sebeok explicitly links cultural operations into a consideration of complex systems via his Biosemiotics, pointing out that communication through language (including visual languages) is the distinctive result of the lower level system (e.g., human language being the result of human origin) and must be considered at a system level including the system of biology and of the society the biology engenders5. In operation, complexity research tells us that the very complexity found in drawing is not just a matter of the number of elements in a system, it is a matter of the elements being capable of meaningful interaction between one another and agents of the system reading the drawing.

That the drawing depends on systems outside of itself to function can be derived from the argument that most of the possible arrangements of mark in a drawing are culturally non-significant: yet the ones in most drawings will be significant in contributing to the work. The total possible number interactions of mark form a vastly larger set than those with significance to a particular culture. At the point of creation, the addition of an agent to review previous work and seed the next cycle of construction takes us beyond accident into the realm of feedback, patterning and evolution6. Now consider repeating this experiment with drawn marks applied randomly, perhaps by a stochastic machine process, the number of completed ‘drawings’ would be vast in comparison with the numbers achieving a functional degree of cultural legibility7. In practice we see that few drawing processes are accidental experimentation or wholly pre-planned. Rather they are the result of a mass of feedback cycles, called Design Moves (Goldschmidt, 1991, Suwa & Tversky, 1997) or Creative Segments (Sun et al., 2014).

The capability of a drafter picking up on these unintended consequences in a productive way is sensitive to the initial conditions, in this case the experience of the drafter. Suwa & Tversky (1997) note that experienced drafters are better than novices at picking up on these unintended consequences, identifying them as productive against the initial brief and incorporating them into subsequent iterations of a work.

Serendipity is desirable characteristic of the drawn system, a statement that may sound counter-intuitive for a system predicated in the design, planning, communication, or externalizing of interior states (e.g., as in phenomenological fine art drawing practice (Harty, 2015), or medical descriptions of drawing as an externalization of pathologies (Rollins, 2005)). The reality of the drawing system is that an a priori one-to-one description of a completed drawing is impossible8. In practice the finalized drawing is the result of a mass of internal feedback loops, both internal to the drafter and external in the viewer.

Such system are however strongly amenable to 'retrodictive' analysis as noted by Krippendorff (1969), allowing the possibility of meaningful post facto analysis of the contribution of the parts to the end state. These leads to the unhelpful hope amongst some drawing teachers and historians that an a posteriori analysis of past work allows for useful predictive preprocessing of potential future work. They may look at the marks made by Goya and divine all sorts of information that connects his technical processes, cultural position, age and state of health at the time the work was made. Which may be seen as a step forward to understanding, and predictive of the elements needed to fabricate a Goya.

In practice, a set of steps recording the construction of a previous drawing will do very little to help you fabricate the next drawing. The influences; material, practice and culture; on the drafter and the viewer are such that we might imitate Goya closely, but it won't be Goya. The atomic nature of the process (drawing a mark on paper) seems simple. The total system (a drawing in a cultural frame) is not. This is what Cilliers names "distance from the system".

The distinction between complex and simple often becomes a function of our 'distance' from the the system, i.e., of the kind of description of the system we are using. A little aquarium can be quite simple as a decoration (seen from afar), but as a system it can be quite complex (seen from close by). (Cilliers, 1998:2)

In the same way the elements of a drawing (a draftsman, media and surface) are superficially simple, the actuality of the system is itself complex. One of the prized qualities of drawings (as imagery) versus photography (as imagery) is the variability of the process; from subject to subject, from drafter to drafter, from viewer to viewer. Variability which is intentionally meaningful in the right cultural system.

Complex and adaptive

Accepting, for the moment, that the drawing (process) is an example of a complex adaptive systems, showing the characteristics of growth and dynamism we can see that the drawing needs to be considered as part of larger network of systems.. Chan notes:

CAS are dynamic systems able to adapt in and evolve with a changing environment. It is important to realize that there is no separation between a system and its environment in the idea that a system always adapts to a changing environment. Rather, the concept to be examined is that of a system closely linked with all other related systems making up an ecosystem. Within such a context, change needs to be seen in terms of co-evolution with all other related systems, rather than as adaptation to a separate and distinct environment. (Chan, 2001: 2)

A drawing, even one completed hundreds of years ago, is CAS precisely because the system is never closed as long as the viewer is an element of the drawing's operation: representing Cillier's "changing environment". The culture of the viewer is an environmental determining factor in the reception of the drawing.

For example, the Dürer drawing The Rhinoceros (1515) is a printed drawing of a Rhino given to the Portuguese crown by Sultan Muzafar II of Gujarat. The work is based on a combination of written testimony, possibly on a single woodcut newsletter (sent by the printer Valentim Fernandes), and a mass of classical myth hybridized with Dürer’s familiarity with contemporary armor. In short the animal as presented is a chimera. Yet for more than two centuries it was regarded as authoritative, which demonstrates a pair of complex characteristics. Firstly the drawing had become downwardly causal on the European idea of ‘rhino’, and secondly when contemporary viewers look at the Dürer work they see a charming folly, where our ancestors saw a documentary record. The marks stay the same, the state of the observer and the drawing co-evolve.

This co-evolution between system and environment is one of the characteristics that makes complexity a compelling model for drawing. Gell-Mann characterizes CASs as:

- Its experience can be thought of as a set of data, usually input ~ output data, with the inputs often including system behavior and the outputs often including effects on the system.

- The system identifies perceived regularities of certain kinds in the experience, even though sometimes regularities of those kinds are overlooked or random features misidentified as regularities. The remaining information is treated as random, and much of it often is.

- Experience is not merely recorded in a lookup table; instead, the perceived regularities are compressed into a schema. Mutation processes of various sorts give rise to rival schemata. Each schema provides, in its own way, some combination of description, prediction, and (where behavior is concerned) prescriptions for action. Those may be provided even in cases that have not been encountered before, and then not only by interpolation and extrapolation, but often by much more sophisticated extensions of experience.

- The results obtained by a schema in the real world then feed back to affect its standing with respect to the other schemata with which it is in competition. (Gell-Mann, 1994: 17)

Gell-Mann's characteristics stand as clear description of a drawing, and its causal effect on its environment.

Drawing emerges

One of the characteristics of CASs is the spontaneous emergence of order, and that this emerging order will be characterized by qualities that are novel, stable and downwardly causal. The emerging order effects the system that supports it and drives it to new an unexpected places. This phenomena is called Emergence. Once again, we can consider how Dürer’s Rhino changed the system that supported it.

Emergence has been observed in stock market fluctuations, intelligence, ecosystems, weather patterns, the chemical composition of proteins and social and cultural systems. In recent years Emergence has been researched in; biological systems (e.g., Kaufman, 1995; Corning, 2002; Holland, 2000), economics (e.g., Whitt & Schultze, 2009), physics (e.g., Laughlin, 2014), Mathematics (e.g., Wolfram, 2002), Linguistics (e.g., Keller, 1995) and visual culture (e.g., Wheeler, 2006; Alexander, 2011, Downs et al., 2008). And while emergence is difficult (some experts say intrinsically impossible) to predict it's effects are very real.

Goldstein observed characteristics of Emergent systems are:

To Goldstein, emergence refers to "the arising of novel and coherent structures, patterns and properties during the process of self-organization in complex systems." The common characteristics are: (1) radical novelty (features not previously observed in the system); (2) coherence or correlation (meaning integrated wholes that maintain themselves over some period of time); (3) A global or macro "level" (i.e., there is some property of "wholeness"); (4) it is the product of a dynamical process (it evolves); and (5) it is "ostensive"—it can be perceived. For good measure, Goldstein throws in supervenience—downward causation. (Goldstein, 1999: 49-72)

These characteristics all appear in drawing: as both verb and artefact.

Radical Novelty: Drawing shows both material and cultural novelty. The material elements of the system involved in the drawing (draughter, drawing tool, surface, etc.) and the cultural frame that supports the system show radical novelty emerging from the drawing when compared to the contributory elements before the drawing occurred. In Figure 4 we Felix the Cat as a sign composed of drawn elements (emerging from drafter and cultural frame), combining with the sign of a bomb (different drafter and cultural frame), combined to make a new composite sign that functions as the unit symbol for the U.S. Navy's VF-31 squadron9.

Figure 4: Caption: Felix the Cat is the product of a specific technical system, operated as a sign in a cultural system, which led to its adoption as a formal U.S. Navy

Coherence: The drawing clearly exists as a distinct 'integrated whole' that supports itself over time. While each mark contributes to the whole, when taken out of context they lack a proportionate effect to the power they contribute to the integrate whole. It is possibly to conceive of a level where the lines are sparse enough to not demonstrate the complexity called drawing: where the drawing hasn't yet cohered. The artist Brian Fay plays (Figure 5) games with effect in creating works where the image is composted of lines indicating brush strokes of an original work. The sparseness of strokes denies the viewer the context for the image to cohere.

Figure 5: Caption: Brian Fay’s ‘Corot’s Woman Meditating’

Global or Macro level: Drawings are readily identifiable as wholes; things unto themselves. This quality of 'thingness' might, possibly, be seen as just an artefact of cultural framing. The framing might, quite literally be a frame or it might be some other sort of cultural device that says this is a 'drawing'. This demarcation of the drawing from its boundary is a game that drafters have played with for many years.

We might think about the work 'Taking a line for a walk' by Maryclare Foa where the work exists as part of the geography of Manhattan (arguably without specific framing). But this work is being framed by both the cultural context (as a performance piece) and by the photographs that record the work (as seen through a Vitruvian Window).

This cultural frame is still a frame, as the cultural dimension always has a role in crystallizing the system that becomes a drawing (as discussed below). With the frame in place we know when we're involved as viewers in the construction of the whole that is the viewed.

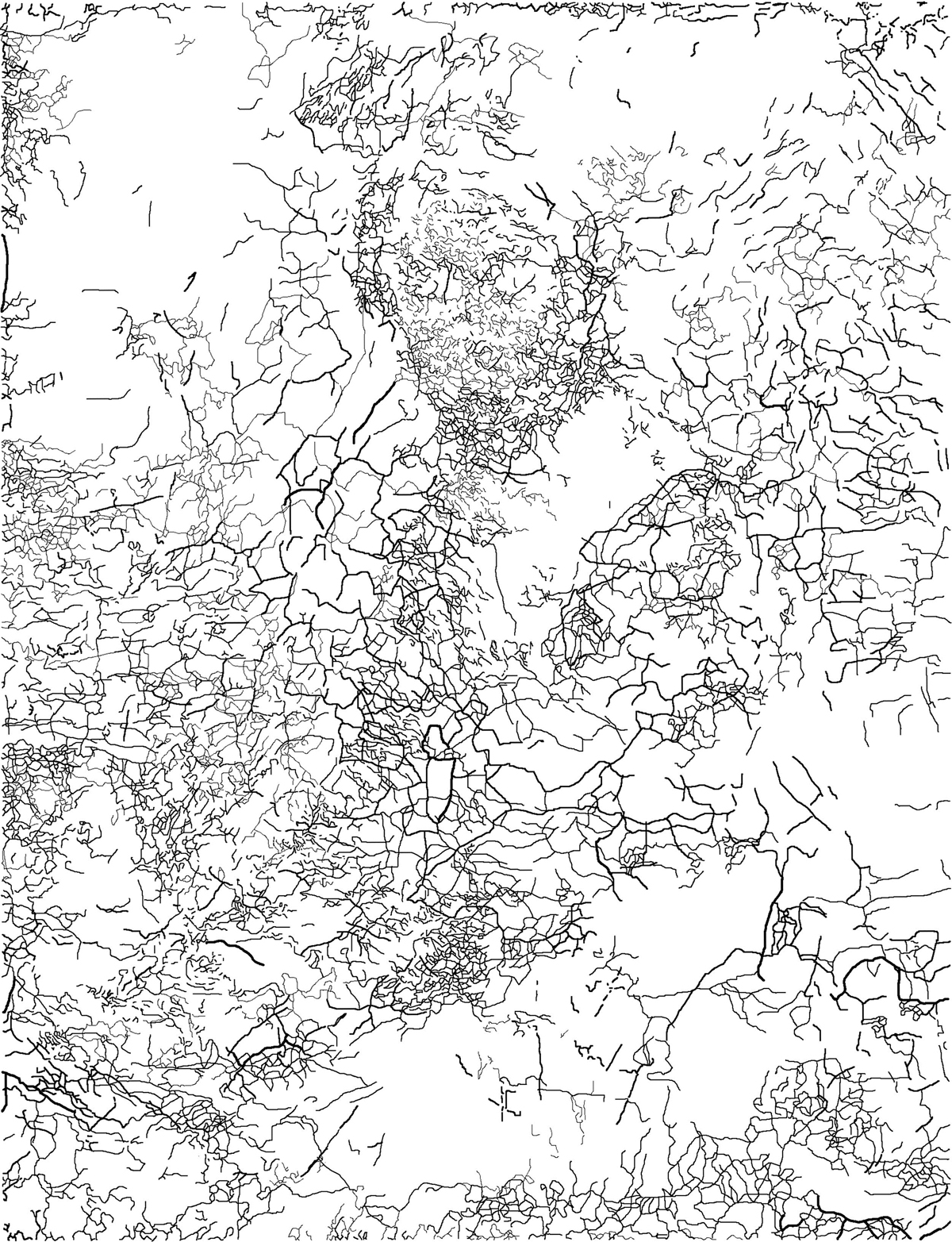

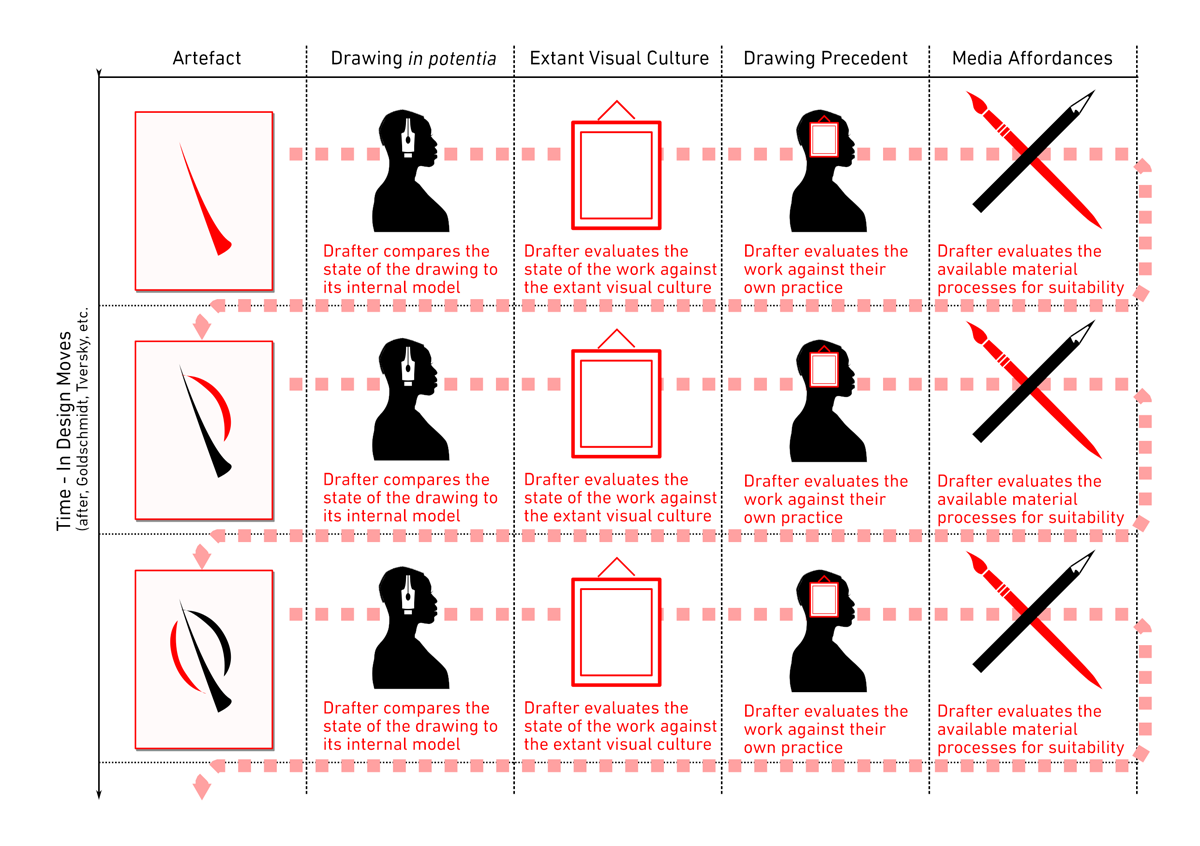

Dynamic Process: The creation of a drawing is nothing if it's not a dynamic process. Drawings are observed to be formed through interplay between different parts of the system; draughtsperson / viewer, material / knowledge, artefact / action. From the developmental drawings of a designer to the gunpowder work of Cai Guo-Qiang drawings are defined by being records of a series of changes of state: an evolution from one state to another, with previous states effecting the possible outcomes of the next (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: The dynamic process of drawing as 'design moves' after Goldschmidt and Tversky.

Ostensive: One of the primary functions of drawings is there ability to be perceived as themselves. That a drawing can be seen is obvious. That a drawing can be seen as having an existence 'apart' from the draughtsperson, yet be of them: dependent on the drafter, sensitive to the initial conditions, of a culture yet distinct from it: are commonly observed characteristics of a drawing10.

Downward Causation: As a designer this is a function of drawing as emergence that is both most apparent and most useful. Drawings make change in the systems that supported their emergence. A drawing can instigate the process of materialization (from a website to a skyscraper). But even drawings never intended to act as a 'paper model' (after Norman & Baynes, 2013) of the world make change in the author (for sure) and in potential for making future drawings. Having made a drawing the author cannot unmake the knowledge of the drawing in making future work: the drawing they made has a causal effect on them.

Charting emergent drawing

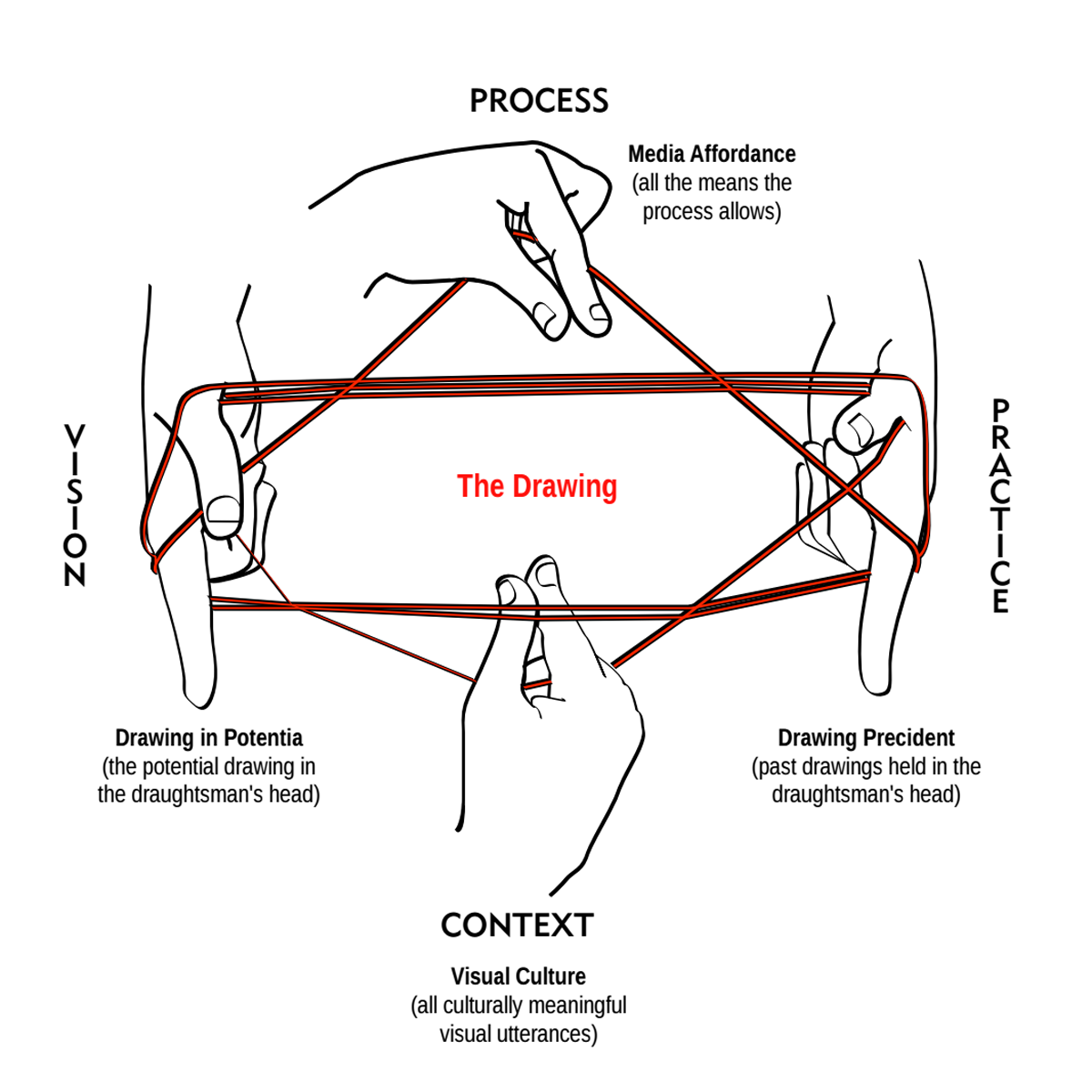

There are a number of ways of visualizing drawing as a complex system, producing emergent artefacts, but most don’t really capture the dynamism of the system. As a professional visualizer I’ve tried to consider an appropriate visual metaphor for drawing status on the razor's edge of emergence (after Waldrop, 1992)11.

As an aid to understanding the variable factors that dominate a drawing, and the ways that they interact and effect one another, I would ask you to consider the Cat's Cradle game as a suitable visualization of drawing as complex and emergent. In this game one or more participants dynamically form patterns of string by reflexively adjusting a simple set of governing parameters (fingers and the finger's position relative to one another).

Despite the small number of variables at play (number of fingers, number of hands and their position) the resultant patterns show evolution, intricacy and variation. Each product is identifiable as distinct from the next, each pattern jumps into existence where there was previously nothing but string.

In this visualization the drawing is the string and the individual hands in play may be thought of as:

- The Drawing in potentia;

- The Media Affordances;

- The Drawing Precedent, and;

- The extant Visual Culture.

Figure 7: As the elements of the Cat’s Cradle of Drawing change the drawing changes – but it is still the child of elements

Flexing of any of the fingers (parameters) simultaneously changes the pattern (the drawing) and causes changes in the position of the other fingers (in this case the conditions contributing to the drawing's creation). This is exactly what we see in the world of drawing. The nature of the work is dependent on its constituting elements and conditions the work is constructed from12. And once made, the work feeds back changes the draughtsperson, the initial dependencies and the work that follows it.

The four elements

The Drawing in potentia is the idea of the completed work in the drafter's mind as they work. The conceptual intention without a present physical manifestation. This may be as vague as a notion for a work, a structural as a formal process of ideation (e.g., a designer's rough) or as tightly devised as an extensive program of future media manipulation (e.g., a fine artists practice), but until the work is materialized it exists entirely in potentia. As noted above the work that comes into existence (in esse) is rarely the same as it was in potentia. This quality of dynamic evolution through drawing, while still being recognizably of the same lineage at the end, is characteristic of emergence.

The drawing in potenia exists as a kind of imagined doppelgänger of the drawing in esse. The draughtsperson will be considering the qualities of the other three elements as they make decisions over the actions they take, and in their internal modelling of future actions. Suwa and Tversky note this process in action: "sketches serve as a 'perceptual interface' through which one can discover non-visual functional relations underlying the visual features" (Suwa & Tversky, 1997: 401). Norman (2010: 19) talks about visual modelling of "... certain core aspects of future reality which cannot effectively be modelled in language or number"13.

The 'affordance' in Media Affordance is a term borrowed; originally from Psychology and laterally from Human Computer Interaction (HCI); commonly though not originally, through the work of researcher Donald Norman and his work on the ways in which humans engage with the physical world around them. In turn Norman borrowed the concept from an earlier psychologist J.J. Gibson who defined the concept of an affordance around the human ability to see a range of possibilities latent in the environment.

To a draftsman a specified combination of media and tool will offer a specific affordance: operations that might viably be enacted with this tool. This is entirely different from tradition. While tradition informs the drafter about possible applications, artists and designers are by their nature curious and experimental. In this way we see someone, like the fine artist Jordan Mackenzie, do something unexpected with graphite and a surface and this way the possibilities afforded by the media expands.

This change of concept in our cultural frame’s understanding of drawing demonstrates emergent qualities: with a novel form of drawing being at one and the same time recognizably a drawing and yet redefining our notion of what drawing is (novel, coherent, existing on a global level, dynamically evolving, ostensive and downwardly causal).

Drawing Precedent is the personal historic process knowledge actively informing the draftsman while they work: both embodied kinaesthetic learning and codified practice knowledge. This is a different class of knowledge than the sort of declarative knowledge that typifies theoretical studies of drawing. The Drawing Precedent is justified through a personal (often physical) experience (a Doxastic Justification rather than Propositional Justification). This form of knowledge is often tacit, formed by internally generated heuristics, and explicitly held in mind as Practice while working (Brew et al., 2011).

Goldschmidt conjectured that sketches give access to various mental images. figural or conceptual, that may potentially trigger ideas in the current design problem. (Suwa & Tversky, 1997: 386)

Lines and marks can be used to represent nascent ideas and perceptions that can then be inspected, extended, and revised. (Brew et al., 2017: 51)

This combination of personal knowledge, physical capability and practice heuristics forms one of the common forms of sensitivity to initial conditions in drawing: closely linked to what Suwa and Tversky called, in Architectural drawing, 'background knowledge'.

Facilitation by external representation derives, not just from its external existence, but from the interaction between the representation and the cognitive processes of interpreting it. (Suwa & Tversky, 1997: 386)

Background knowledge in the domain of architectural design includes (a) domain knowledge about structures and materials for fulfilling certain functions, and spatial arrangements; (b) standards for doing the aesthetic and preferential evaluations for their own design decisions; and (c) knowledge about the relevance and influence of the architectural designs to/from the social contexts, and the environments in which the architecture is built. (Suwa & Tversky, 1997: 389)

The Drawing Precedent is distinct from the Visual Culture in that while the Visual Culture will, at some time, have informed and directed the drafter's practice this information will be seen as belonging to an external field of reference and connotation, whereas the Drawing Precedent is something held as personal because it exists as a recalled memory of physical action. In this way it feels personal and authentic.

Visual Culture is, by contrast, the environment in which the work grows. Not necessarily as a connected part of a system of signification and consequently dependent on that system for its ability to act (e.g., an illustration). But, including the non-figurative, conceptual or abstracted work, which is defined in contention or opposition to the system of signification. As the biologist and systems theorist Humberto Manturana would note, any element that contributes to or is acted on by a system is a part of the system (Maturana & Varela, 1992: 135). In systems terms a drawing is part of the greater visual cultural system when it acts on or is acted on by the visual cultural system14.

Also embedded within the Visual Cultural is the observer (and the observer has a role to play in the drawing). Within this context even the drafter's Drawing Precedent becomes recast through the operation of the visual cultural system, informing the reception of the current work in relation to both the history of the field and towards the previous work of the draftsman.

In the Cat’s Cradle metaphor, as soon as this idea is manifest (drawn) the fingers of the Drawing in Potentia hand flex and in flexing change the pattern. The new drawing changes the possibilities inherent in the Media Affordances; changing the drafter’s personal Drawing Precedent; and making changes to the Visual Culture through the addition of this new work. The pattern (drawing) made in this instance changes the elements that have made it in the first place, and while the fingers may attempt to form the same pattern again they never can; because the pattern has changed them.

Conclusion

Using complexity and emergence as a model of drawing offers a way of understanding the practice that opens the black box, while supporting the experience drafter’s of their drawing practice. Framing drawing as something more than a personal endeavor disconnected from the world it inhabits. Drawing, if it is to be understood, needs to be seen as an activity that happens simultaneously inside the heads of all the participants of the drawing and in the world between them. Its power to operate being the emergent effect of the interaction of something more than the sum of the elements contributing to the work.

For the drafter this suggests that personal practice can usefully be extended, refined and revitalized by making changes to those things in the world that are amenable to personal change: the cultural framework the drawing operates in, a change of media and novel sources of inspiration are all well understood as ways of enriching existing practice. For the visual culture theoreticians it suggests limits to the insight that theoretical positions can have when divorced from practice: the work will continue to surprise us. The paper points out that nature of the underlying processes means that while we cannot predict the form the change will take. The work produced will, like our children, still carry our stamp; and like a child, will be something completely new, wonderful and beyond us.

Footnotes

References

Adams, D. (1989). The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, ISBN 9780345391810 (1995).

Alexander, V.N. (2011). The Biologist's Mistress: Rethinking Self-Organization in Art, Literature, and Nature, ISBN 9780984216550.

Brew, A., Kantrowitz, A. and Fava, M. (2011). "Thinking through drawing: Practice into knowledge," in Proceedings of an Interdisciplinary Symposium on Drawing, Cognition and Education, pp. 123-125, link.

Brooks, M. (2009). "Drawing, visualization and young children's exploration of 'big ideas'," International Journal of Science Education, ISSN 0950-0693, 31(3,1): 319-341.

Cilliers, P. (1998). Complexity and Postmodernism: Understanding Complex Systems, ISBN 9780415152860.

Chan, S. (2001). "Complex Adaptive Systems," in ESD.83 Research Seminar in Engineering Systems, MIT, link.

Corning, P.A. (2002). "The re-emergence of 'emergence': A venerable concept in search of a theory," Complexity, ISSN 1076-2787, 7(6): 18-30.

Dennett, D.C. (1989). The Intentional Stance, ISBN 9780262540537.

Dennett, D.C. (2003). "Who's on first? Heterophenomenology explained," Journal of Consciousness Studies, ISSN 1355-8250, 10(9-10): 19-30, link.

Downs, S., Marshall, R., Sawdon, P., Selby, A, and Tormey, J. (eds.) (2008). Drawing Now: Between the Lines of Contemporary Art, ISBN 9781845115333.

Gell-Mann, M. (1994). "Complex adaptive systems," in G. Cowan, D. Pines, and D. Meltzer (eds.), Complexity: Metaphors, Models, and Reality, ISBN 9780201626063.

Goldschmidt, G. (1991). "The dialectics of sketching," Creativity Research Journal, ISSN 1040-0419, 4(2): 123-143.

Goldschmidt, G. (1994). "On visual design thinking: the vis kids of architecture," Design Studies, ISSN 0747-9360, 15(2): 158-174.

Goldschmidt, G. (2003). "The backtalk of self-generated sketches," Design Issues, ISSN 0747-9360, 19(1): 72-88, link.

Goldstein, J. (1999). "Emergence as a construct: History and issues," Emergence, ISBN 1521-3250, 1(1): 49-72.

Goel, V. (1995). Sketches of Thought, ISBN 9780262071635.

Hall, E. (2008). "My brain printed it out! Drawing, communication, and young children: A discussion," presented at the British Educational Research Association Annual Conference, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, 3-6 September, link.

Harty, D. (2015). "Trailing temporal trace," Drawing Ambiguity: Beside the Lines of Contemporary Art, ISBN 9781784530693, pp. 51-65.

Holland, J.H. (2000). Emergence: From Chaos to Order, ISBN 9780738201429.

Ishii, H., Kobayashi, M. and Grudin, J. (1993). "Integration of interpersonal space and shared workspace: ClearBoard design and experiments," ACM Transactions on Information Systems, ISSN 1046-8188, 11(4): 349-375.

Kandinsky, W. and Max B. (1963). Essays über Kunst und Künstler, ISBN 9783716501818.

Kantrowitz, A., Fava, M. and Brew, A. (2017). "Drawing together research and pedagogy," Art Education, ISSN 0004-3125, 70(3): 50-60.

Kauffman, S. (1995). At Home in the Universe: The Search for the Laws of Self-Organization and Complexity, ISBN 9780195111309.

Keller, R. (1995). On Language Change: The Invisible Hand in Language, ISBN 9780415076722.

Krippendorf, K. (1969). "Values, modes and domains of inquiry into communication," Journal of Communication, ISSN 0021-9916, 19(2): 105-133.

Laughlin, R.B. (2014). "Physics, emergence, and the connectome," Neuron, ISSN 0896-6273, 83(6): 1253-1255, link.

Lawson, B. (2004). "Schemata, gambits and precedent: some factors in design expertise," Design Studies, ISSN 0142-694X, 25(5): 443-457.

McManus, I.C. Chamberlain, R., Loo, P.-W., Rankin, Q., Riley, H. and Brunswick, N. (2010). "Art students who cannot draw: Exploring the relations between drawing ability, visual memory, accuracy of copying, and dyslexia," Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, ISSN , 4(1): 18-30 link.

Magnani, L. (2013). "Thinking through drawing: Diagram constructions as epistemic mediators in geometrical discovery," The Knowledge Engineering Review, ISSN 0269-8889, 28(3): 303-326 link.

Maturana, H.R. and Varela, F.J. (1992). The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding, ISBN 9780877736424.

Norman, D. (1999). "Affordance, conventions, and design," Interactions, ISSN 1072-5520, 6(3): 38-43.

Norman, E. (2010). "Models of change: The impact of 'designerly thinking' on people's lives and the environment... Ken Baynes" Design and Technology Education: An International Journal, 14(2): 3-7, link.

Norman, E. and Baynes, K. (2013). "Modelling and designerly thinking: STEM to STEAM," TRACEY / Thinking Through Drawing Seminar, link.

Rollins, J.A. (2005). "Tell me about it: Drawing as a communication tool for children with cancer," Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, ISSN 1043-4542, 22(4): 203-221.

Ruskin, J. (1971). The Elements of Drawing, ISBN 9780486227306.

Russell, B. (1992). The Analysis of Matter, ISBN 9781614277217.

Schenk, P. (1991). "The role of drawing in the graphic design process," Design Studies, ISSN 0142-694X, 12(3): 168-181.

Schenk, P. (2016). Drawing in the Design Process: Characterizing Industrial and Educational Practice, ISBN 9781783206797.

Schön, D.A. (1984). The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action, ISBN 9780465068784.

Sun, L., Xiang, W., Chai, C., Yang, Z. and Zhang, K. (2014). "Designers' perception during sketching: An examination of Creative Segment theory using eye movements," Design Studies, ISSN 0142-694X, 35(6): 593-613.

Suwa, M. and Tversky, B. (1997). "What do architects and students perceive in their design sketches. A protocol analysis," Design Studies, ISSN 0142-694X, 18(4): 385-403.

Suwa, M., Gero, J. and Purcell, T. (2000). "Unexpected discoveries and S-invention of design requirements: important vehicles for a design process," Design Studies, ISSN 0142-694X, 21(6): 539-567.

Vasari, M.G. (1906). Le Vite de' Piu Eccellenti Pittori, Scultori, E Architettori, ISBN 9782012690639.

Waldrop, M.M. (1992). Complexity: Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos, ISBN 9780671767891.

Wheeler, W. (2006). The Whole Creature: Complexity, Biosemiotics and the Evolution of Culture, ISBN 9781905007301.

Whitt, R.S. and Schultze, S.J. (2009). "The new 'emergence economics' of innovation and growth, and what it means for communications policy," Journal on Telecommunications and High Technology Law, ISSN 1543-8899, 7(217), link.

Wolfram, S. (2002). Cellular Automata and Complexity: Collected Papers, ISBN 9780201626643.