Social enterprise development in nonprofits:

Business model as a structural attractor

Tricia Fitzgerald, Jamie Newth, Deborah Shepherd, and Christine Woods

University of Auckland Business School, NZL

ABSTRACT

The disruptive challenges of bringing commercial businesses models and associated processes into nonprofit organizations are often significantly underestimated. This article address the lack of understanding of the development of social enterprise within nonprofits and, specifically, how nonprofits introduce and accommodate a commercial business model into an organization with a social purpose is addressed. Additionally, the article seeks to consider the most significant changes made to accommodate the business model alongside the social purpose. This research provides further clarity on the introduction and accommodation of a social enterprise within an existing nonprofit. Using the concept of the structural attractor, the model offered expands the work of a number of complexity writers into the specific context of social enterprise within a non-profit.

Introduction

With uncertain income available from both governments and the public alongside growing social need, nonprofits are increasingly exploring innovative ways to generate funding and increase financial autonomy (Morris et al., 2007). However, from the extant social enterprise literature, few appear to be commercially successful (Foster & Bradach, 2005; Oster et al., 2004). The disruptive challenges of bringing commercial processes into nonprofit organizations are often significantly underestimated (Kirkman, 2012).

Although many writers reserve the term 'social enterprise' for a stand-alone hybrid organizational model (Battilana & Dorado, 2010; Emerson, 2003), social enterprise units can and do exist within nonprofits (Kerlin, 2010; Young, 2001). With their existing social missions, infrastructure, and networks, nonprofits might be considered useful vehicles within which innovative social enterprises could flourish. However, there is still much to learn to fully understand how, within the context of nonprofits, social enterprises might be successfully generated and sustained. We suggest that complexity theory, as a theoretical lens, can assist in developing this understanding.

This article seeks to address the lack of understanding of the development of social enterprise within nonprofits. Specifically, two research questions are explored. Firstly, how do nonprofits introduce and accommodate a commercial business model into an organization with a social purpose? And secondly, what are the most significant changes made to accommodate the business model?

This article is organized into three parts. We begin by first outlining the theoretical framework used within the research. We then discuss the research method undertaken and briefly outline the case studies. Finally, drawing on the primary findings of business model behavior, we argue that the business model can be usefully perceived as a structural attractor that links the key components of the business, reflecting and generating the co-evolution occurring.

Theoretical background

Social enterprise

As a relatively new academic discipline, the academic literature on social enterprise has grown rapidly in the past 20 years (Battilana & Lee, 2014). Definitions of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship remain overlapping and contradictory, ranging between the use of entrepreneurial means to either generate income or create social change (Brourad & Lavriet, 2010; Defourny & Nyssens, 2008). The most relevant definition for this research is consistent with the earned income approach (Defourny & Nyssens, 2010). That is, social enterprise is 'an organization which has a social, cultural, or environmental mission, that derives a substantial portion of its income from trade, and that reinvests the majority of its profit/surplus in the fulfillment of its mission' (Department of Internal Affairs, 2013: 1). The inherent focus on generating commercial income reflects the interest of nonprofits in using social enterprise primarily as a means to increase their financial self-sufficiency.

The most frequently mentioned feature of social enterprises within the academic literature is their hybridity in balancing both social and commercial objectives (Galaskiewicz & Barringer, 2012; Peattie & Morley, 2008). While the social aims may predominate and generally nonprofits do not normally distribute profit to individual shareholders, the commercial goals are a mechanism to achieve social outcomes and are therefore vital for the organization (Haigh et al., 2015; Trivedi & Stokols, 2011). However, some commentators argue that social and commercial organizational forms may be considered different organizational species (Young et al., 2016. With social enterprises straddling both, sometimes uncomfortably, many possible responses are possible to this duality of logics (Billis, 2010; Dart et al., 2010).

A complexity perspective on social enterprise

There is no commonly accepted overarching definition of complexity. However, for the purposes of this project, Uhl-Bien and Marion (2008) describe complexity as the study of the dynamic behaviors of complexly interacting interdependent, networked, and adaptive agents who are bound in a collective dynamic by common need, and are working under conditions of internal and external pressure, leading to emergent events such as learning and adaptations.

When nonprofits pursue both economic and social value, they are likely to be in a state of continual change and at risk of instability with insufficient resources, powerful external influences and active internal dynamics at play (Alter, 2009; Russell & Duncan, 2007). It is therefore plausible to see evolving organizations with simultaneous social and commercial approaches as complex adaptive systems (Swanson & Zhang, 2011). Complexity, as a theoretical lens, is increasingly adopted to understand these dynamic systems within social entrepreneurship or a developing social enterprise (Rhodes & Donnelly-Cox, 2008; Shepherd & Woods, 2011; Smith et al. 2012). In particular Gibbons and Hazy (2017) directly explore the complexity leadership requirements inherent in the complex value distribution models of 'distributed' social enterprises. In their case, not only was the complexity driven by the scale and distributed nature of the organization, but by the dynamism of its value creation and distribution strategies.

One complexity concept useful for explaining some of the changes experienced and/or observed are structural attractors. An attractor is the state towards which a system tends, and can be anything that attracts nearby solutions, including ideas, things, people or practices (Mackenzie, 2005; Tsoukas, 1998. It is termed an 'attractor' because there is at least one stable attractor within the dynamic system of interacting entities and activities, drawing activity towards it, shaping patterns of human interaction and the systems they create (Lythberg, Woods, & Henare, 2015). In complexity terms, an attractor represents an area of phase space, where all possible states of a dynamical system exist, that the system tends to move towards.

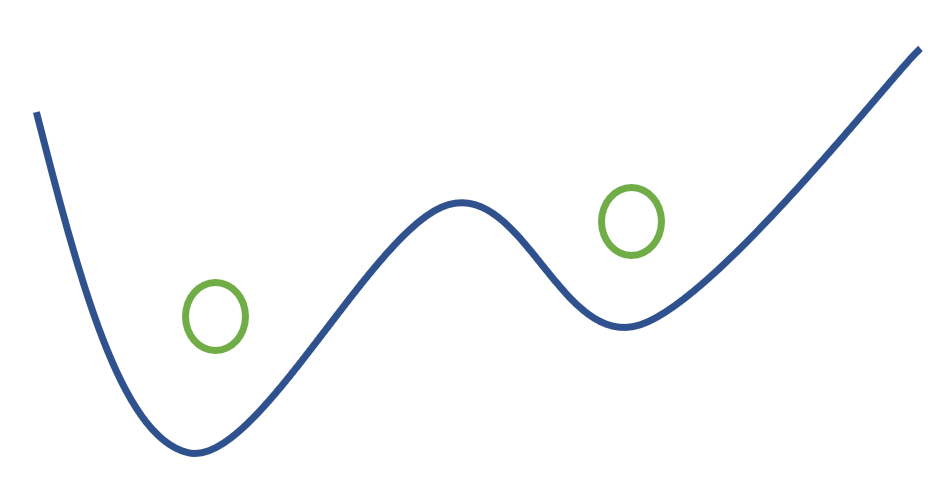

As shown in Figure 1 below, when elements of the system stay close to the attractor, a basin of attraction forms which represent a relative minimum (or maximum depending on sign) energy state surrounded by potential barriers (Hazy & Backström, 2013). If the basin is deep, as depicted on the left of Figure 1, the attractor is likely to be more stable, effectively constrained by stronger barriers and therefore able to withstand change. Resilience refers to the magnitude of a disturbance that can be absorbed before the system changes and moves to another phase state (Folke et al., 2010; Young & Kim, 2015). Complex systems, such as organizations, are sensitive to initial conditions and often oscillate between stability and instability at the edge of chaos (Plowman, Baker, Beck, & Kulkarni, 2007). In simpler organizational terms, basins represent phases of stability and resilience in that it requires greater amounts of disruption to overcome the barriers that form the basin. However, basins also represent situations whereby organizations must overcome barriers and pass through unstable phase states to reach another (stable) basin. An example of this would be a shift to a new business model configuration of a nonprofit towards a commercial social enterprise. A organization (system) operating in a new basin will operate with a structure which represents a different dynamic state and with different barriers, at least one of which separates the new state from the prior one (Hazy, 2008).

Figure 1 is a qualitative illustration of the principles of attractor basins whereby the curve represents potential stability and the circles represent possible states of the system over time.

Figure 1: Attractor Basin (Hazy & Backström, 2013)

Structural attractors are 'structural' in that they reflect the nature, characteristics, synergies and conflicts of the constituent components with multiple interacting attributes and components within the system and are applied by a group of diverse and autonomous individuals (Allen, 2001a, 2001b; Allen, Strathern, & Baldwin, 2007). Hazy (2011: 6) contemplates the example of a warehouse or factory with its characteristics, including location, that both reflect the nature and impact on the dynamics of the business and its eco-system of customers and suppliers, employees. Structural attractors can be manufactured, physical, natural or symbolic (Hazy & Backström, 2013). This research suggests that business models can meet this criteria. For example in a nonprofit organization the business model often embodies and informs organizational identity and culture, the tension between desires to innovate with risk appetite, and the synergy of philanthropic sentiment with mission driven staff, and so on.

Research design and case context

Because theoretical development in social enterprise is still nascent, this research adopted a qualitative approach and an abductive strategy (Daft, 1983) to better understand the complex phenomena involved. A case-based research method was used (Eisenhardt, 1989), as is common in social enterprise research.

With relatively little social enterprise development among nonprofits in New Zealand, the geographic context of the study, three heterogeneous cases were selected to explore whether emerging features and themes were prevalent or unique (Denzin, 2002). The nonprofits included in the research were all well-established, operating for over ten years, and experienced contractors to government. Each nonprofit had been actively developing social enterprises in the previous one to two years prior to the research project and was still in this development process. Variability was sought between the nonprofits across the sector in which they operated, and their length of history. There are no legal frameworks specifically designed for social enterprise in New Zealand and all three cases took the legal form of either a charitable trust or an incorporated society (Department of Internal Affairs, 2013), as can be seen in Table 1 below.

| Social Enterprise | NonProfit sector | Number of staff in social enterprise | total nonprofit staff | Legal Form | Social Enterprise Structure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Merge Café | Social development | 5 | 300 | Charitable trust | Part of homeless service |

| Ako Books | Early childhood education | 9 | 500 | Charitable trust | Separate organization |

| Changeability | Mental health | 9 | 120 | Incorporated society | Division |

Table 1: Case overview

In four time periods over an eighteen month period, a total of 54 individual interviews and focus group discussions were conducted alongside key document analysis across the three organizations to develop an in-depth account of each case (Bryman, 2003). Codes were developed in an iterative manner from the data directly in addition to theory. The analysis included the exploration of key concepts drawn from the literature on complexity and business models, and compared and contrasted them with research participants' narratives.

Because nonprofits are developing social enterprises with a commercial focus, a business model framework was considered useful to better understand the nature of that which was being imported into the nonprofit. The business model outlines the logic of core business operations and strategies, and therefore enables the examination of commercial business development over time (McGrath, 2010; Osterwalder et al., 2005). Osterwalder's Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder et al., 2010) was used as a mediating artefact upon which the research interviews were based. The Business Model Canvas comprises key internal and controllable features of the business architecture: customer segments, customer relationships, channels for reaching customers, value proposition(s), key activities, resources and partners delivering customer value, revenue streams and the cost structure. These components enable business models to be compared across organizations and across time, which may help to advance social enterprise theory (Morris et al., 2005; Perrini & Vurro, 2006).

Themes were explored through the data collected at each time point in conjunction with extant literature and then tested finally with research participants to ensure the researcher's conclusions resonated with the participants' viewpoints. Each of the three illustrative cases will be briefly described to provide contextual background.

Case outlines

Changeability

Changeability is a social enterprise within a well-resourced 20+ year-old regional mental health agency, 'Connect Supporting Recovery' (Connect). Connect employs 120 full time staff operating across ten sites. Leaders sought possibilities for income generation to increase organizational financial sustainability.

Involving all Connect staff, the idea of a corporate consultancy emerged, based on a tool developed and used internally to encourage client readiness for change. While the existing tool had a strong theoretical base, it was adapted and rigorously tested for corporate use. Funded by Connect reserves, the consultancy offered the marketplace a tool and expertise that could help individuals, teams and organizations move successfully through change. The consultancy provided workshops and training to organizations undergoing changes in role, structure, process, or technology. The service aimed to strengthen their customers' existing change strategies and provide practical management recommendations. As a division, the consultancy was separately branded but shared Connect's internal resources, such as reception and management.

With a commercial advisory board to support the consultancy, a commercial manager was recruited to Connect to imbue commercial skills and acumen within the organization but continued to be strongly connected to Connect through internal appointments and their commitment to Connect's values.

During the period of this study, the consultancy did not provide additional revenue to Connect, however, it was seen to bring Connect multiple benefits, including leading internal change and developing financial awareness and entrepreneurship within Connect and doing preventative work in the wider business community.

Merge Café

Merge Café is a social enterprise that is part of a large regional church-based social development agency, Lifewise. "Turning lives around" is the articulated purpose of this 160-year-old agency that employs over 300 staff. For eighty years a soup kitchen for homeless people had operated in a large central city hall, but in 2008, with staff support, newly appointed managers decided to try something different, and in 2010, a café was leased in a central city street. In addition to providing good food at reasonable prices and the opportunity for integrating homeless people with other members of the community, the café also aimed to attract homeless people to its attached social work support services that worked closely with a large range of community agencies.

Unlike the soup kitchen, where food was free, a small charge was made for basic meals. This change was seen as compatible with the Lifewise core values of encouraging interdependence, community and connectedness. Counter food was also offered at just below market rates for the local business and residential population. During the research period, the café was contributing around 40% of its costs and remained heavily subsidized by Lifewise and its funders.

Café expertise was brought into the organization to assist and train the service manager, a highly experienced mental health social worker. He found that managing Merge required a very different approach than his more autonomous social work team. Trying to combine the different business models and at times competing approaches resulted in the two parts of the homeless service operating more separately than initially envisaged by senior decision makers within Lifewise. Some tensions emerged between those supporting traditional social work approaches (some staff and managers) and those seeking a self-funding café (some managers and consultants). Some social workers have seen the rise in Merge meal pricing as too high for the homeless population but also too low for the general population. Questions of how much financial contribution the café should generate for Lifewise and how commercially focused the café ought to be were keenly debated.

Ako Books

Ako Books is a social enterprise established by a large but financially stretched 75-year-old parent-led early childhood organization, Playcenter, that has sought to create social change through education, empowering both adults and children to play, learn and grow together. This national service supported over 15,000 children from birth to school age in 490 centers. Playcenter started to publish books in 1974 primarily for members through a dedicated volunteer management committee, but with declining volunteer support and after extensive internal consultation, Playcenter agreed to establish a subsidiary to raise money for its owners, and a publishing social enterprise emerged.

The publisher shared many Playcenter values, including the importance of community along with minimizing rules and bureaucracy. However, Ako Books also sought rapid commercial decisions and supported the idea of structural separation from Playcenter.

Following a rebranding exercise, Ako Books underwent a further restructure, employing new people with commercial experience to design fresh service systems with a stronger customer focus. However, due to resource constraints, break-even was not reached in the research period. Generating sales, and therefore cash flow presented the greatest challenge to survival for the social enterprise.

Findings

Business model capabilities

A number of elements of the business model across the cases were relatively undemanding for the nonprofit and therefore deepened, stabilized and entrenched the structural attractor, as can be seen in Table 2. These activities were not significantly different to operationalizing a social service. Generating and testing the value proposition, and identifying customer segments, the type of desired customer relationships and the key activities required for the business were all achieved and stayed relatively stable over the research period. Partnerships morphed over time but the nonprofits in this research had little trouble in forming and nurturing pivotal relationships. Participants in all cases spoke of an intense focus on containing costs.

| First order concepts from data | Second order theoretical themes | Aggregated Dimension |

|---|---|---|

| Activities are clear | Business model – capabilities | Business model is a structural attractor |

| Defining customer segments | ||

| Developing customer relationships and responsiveness | ||

| Testing and refining the value proposition | ||

| Building partnerships | ||

| Controlling costs | ||

| Getting the business model right | ||

| Communicating with and engaging customers | Business model – capability challenges | |

| Costing and pricing the product | ||

| Generating revenue | ||

| We have a hard business model | ||

| Acquiring the skills needed (e.g., sales and marketing) | ||

| Working with uncertainty, risk and failure |

Table 2: Business model as structural attractor dimension

Merge formally acknowledged the broadening of its customer segments as it had envisaged to include the working poor and people at risk of homelessness during the research period. They wanted to work at the preventative end of homelessness and with people who wanted to turn their lives around.

All of the social enterprises understood the importance of offering something valued by the customer and each tested their value propositions in different ways. Changeability took one year to develop and test their offer. Merge tested their homeless customers' acceptance of having to pay a small amount in small experiments and their leased premises allowed flexibility in service provision. Ako Books had already tested demand for their offering as a small Playcenter division. Value propositions therefore remained largely stable, although there were some important changes. Merge began to develop a catering service within the café, aiming to sell to corporates who wanted to demonstrate corporate social responsibility, but initially sold internally and to key supporter organizations. Changeability realized over time that their mental-health expertise was valuable for some clients and so added that to their value proposition.

Accustomed to collaboration, each social enterprise continued to develop both informal and formal partnerships throughout the research period. Merge developed several partnerships with residential and other relevant providers during the research period, in addition to their large group of existing community, government and funding partners. Changeability's management prided itself on its ability to form resilient relationships, and formed a strong partnership with a significant corporate customer, started developing links with other change consultancies, liaised with the Global Women's Network and saw key contractors as partners. Ako Books worked hard on developing positive relationships with their authors, and developed relationships, if not partnerships, with some large businesses and their customer base connected to Playcenter.

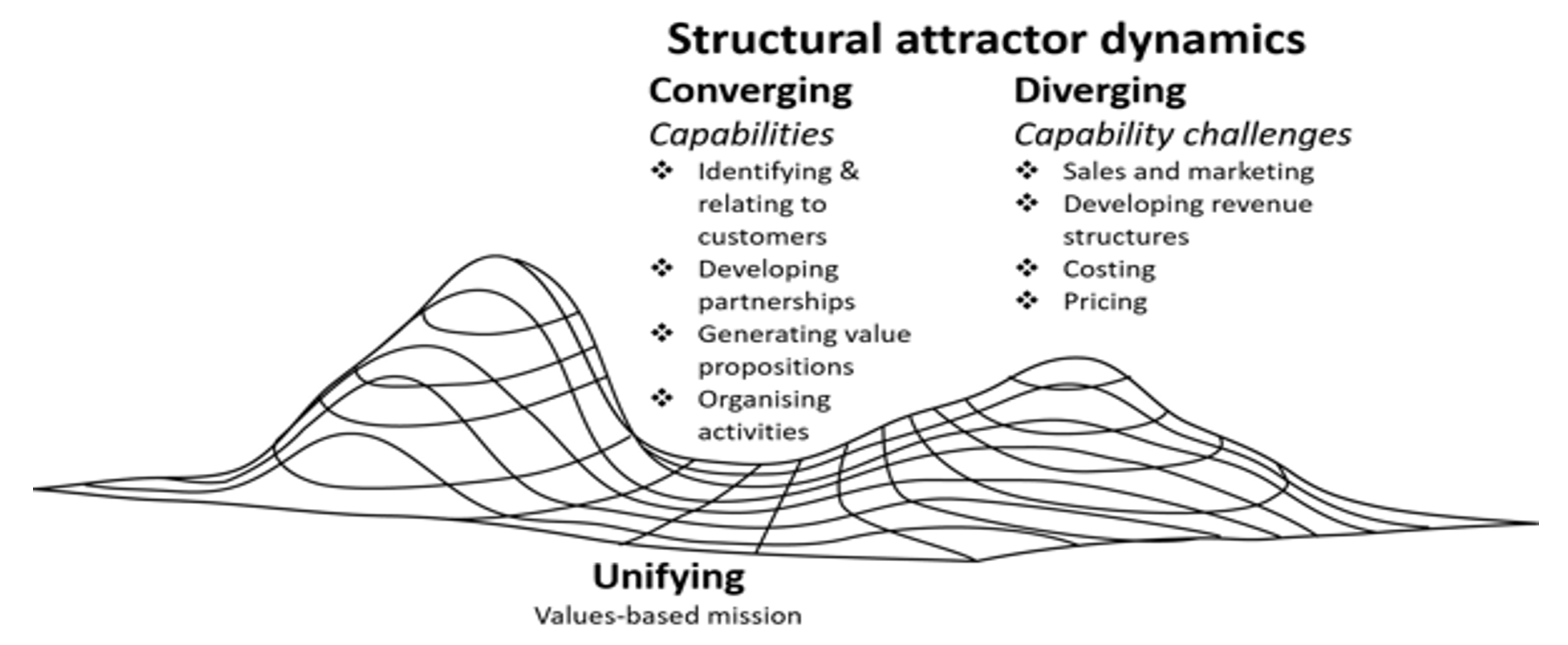

Column one of Table 2 summarize the data drawn from participants reflections on imperatives and challenges regarding the development of social enterprise business models in their respective organizations. Analysis and synthesis of these findings generate the second order theoretical themes and are the bases for the categorization of divergent and convergent dynamics depicted in Figure 2. Divergence was introduced to the system as commercial activities were tackled and commercial personnel introduced. Divergent activities comprised business model activities that were not traditionally necessary in a nonprofit and therefore required new and different skills. Unsurprisingly, these aspects of the business model were the sources of greatest challenge in all of the cases. There were some areas of commercial skill that were in short supply, and to some degree these destabilized the new social enterprise, making it easier to move towards or back to another attractor, such as a purer social or commercial business model, depending on the nonprofit's conscious or unconscious inclinations. For example, at Merge Café the necessary restructuring to hire commercial personnel and the development of new operating systems pushed the organization to a much less stable place outside their native capabilities and lead to distress from social workers regarding staffing changes and the new pricing structures that were implemented. Likewise at Ako Books, the restructuring of staff out of established roles and the implementation of new commercial processes created significant instability. These divergent activities were intentional efforts to push the organizations toward new business models with the desire that these ultimately become stable structural attractors. However, the instability that was experienced in the organizations as a result was significant and challenging for leaders and staff, and the lack of commercial capabilities prevented them from settling into a new stable attractor at the speed that was intended. Instability therefore lingered far longer than anticipated.

New skills and knowledge were needed, especially in the areas of sales and marketing, pricing and costing. For example, Merge Café hired a hospitality consultant, enabling a greater focus on customer service, communication channels, sales, and costing and pricing. Changeability had access to commercial skills through its Advisory Group, some of whom had experience with start-ups, change management, and human resource management. Ako Books employed staff with more general commercial backgrounds to develop the website, costing and selling systems needed, and later contemplated, then acquired, publishing skills on the board.

Finding the right price for the market and costing individual services and products were new challenges for all the nonprofits that tended to cost whole programmes rather than individual products or services. Merge Café increased the price of meals for the homeless from three to four dollars, streamlined their expenditure and struggled to identify how to stagger prices for different customer groups. Ako Books rationalized their prices and decreased the discounts given to different customer segments. Changeability experimented with charging a commission from contractor services and debated pricing approaches in comparison to employing staff, and there were differences in views as to the level of pricing appropriate for the market.

Commercial logics

Each case reported that the specific business model they built was a difficult one and that an easier business model might have been found. Café management thought it could have been easier to have started a brand new café if they were clear it was to operate as a business from the beginning.

Similarly, Ako Books board members found changing from the nonprofit operation to a commercial business difficult, especially changing the mind-sets of existing staff. The Changeability manager thought it would have been easier to have bought an existing business or start with a product or market that they were already familiar with. The three nonprofits were eager to optimize the business model to achieve as much commercial income as possible in addition to progressing their mission.

In summary, some components of the business were relatively easy to develop for all the nonprofits. In particular, identifying value propositions, customer segments, desired customer relationships, planning and operationalizing key activities, and developing partnerships were all achievable within the organizations' capacity. Furthermore, the three case studies were all skilled service providers in their area and demonstrated entrepreneurialism and experimental approaches with the social enterprise. Most challenging were those business model components that were new to the nonprofit. Engaging with scattered customers who had many choices of service, developing effective marketing channels, costing and pricing services competitively and managing higher levels of uncertainty required skill and processes that were not usually required.

Each business model had its own challenges, but a number of challenges were shared by all. Developing a range of new skills and new logics in a new sector, in which there was greater short-term uncertainty than experienced within the nonprofit, may have made any business model challenging. The mission of the organizations studied here did not change. The fundamental dimension that was shifting in the creation of the new business models they sought to create, which is the source of the divergent activities, relates to their relationship with value. In simple terms the new (divergent) practices of social enterprise business models sought to capture more of the value that was being created by the organizations. The use of structural attractors as a lens in social enterprise research, and social entrepreneurship research more broadly, could make use of this distinction (cf. Gibbons & Hazy, 2017). That is, it's not just a shift from old practices to new practices in new business model development that creates instability per se, rather it is when those practices challenge fundamental beliefs about how the organization operates. In these cases, it was the shift from solely creating value for others to seeking to capture more of that value to create financial independence or sustainability, or to fund other on-mission activity.

Discussion

As the business model reduces the complexity of core social enterprise activities (Maguire, 2011), it offers convergence dynamics or stabilizing and clarifying context for the organization (Goldstein et al., 2009). If the structural attractor basin is perceived as a valley, some features of the business model deepen the attractor corral, making it harder to move away from it. In contrast, divergence refers to the generative dynamics that draw the attractor and organization in a different direction (Goldstein et al., 2009). Underlying both and holding the attractor in place are some unifying dynamics (see Figure 2). Those unifying dynamics are understood as the fundamental values and purpose of the organization, but as Gibbons and Hazy (2017) discuss in some detail, it is ultimately the relationship with the communities that the organizations exist to serve that drives unifying behavior. For example, at Merge Café although social workers held on traditional ideals of feeding people for free, the values of the organization and their relationship with their homeless customers were of reciprocity and mutual exchange. In this context price increases and commercial hospitality practices are challenging, but do not ultimately violate those underlying values.

In each of the cases there were some components of the business model that were similar to nonprofit service development. They were therefore relatively straightforward in their implementation, requiring the least amount of change. Other components required new areas of skill, were more challenging in implementation and changed more frequently during the research period.

Figure 2: Business model as a structural attractor (adapted from Allen, 2001b; Goldstein, Hazy, Silberstang et al., 2009; Hazy, 2011; Young & Kim, 2015)

Figure 4 is an illustrative, qualitative depiction of the relative stability and instability created by convergent and divergent capabilities. The figure illustrates the attractor basin in the center of the landscape where the organization is most stable. The mound to the right represents the unstable position of the organizations as the attempt to transition towards a new attractor.

The business model, as a structural attractor, represents a reduced set of business activities from all possible alternatives that appear to work together synergistically. Its components (value proposition, customer channels, and so on) interact in a complementary way to shape the social enterprise, and they stimulate positive or negative feedback to support or challenge the viability of the business, resulting in further adaptations made by the personnel involved. For example, testing the value proposition stimulates activity and decisions for future communication channels or revenue streams.

As is outlined in relevant complexity literature (Goldstein et al., 2009; Hazy, 2011), there were unifying dynamics occurring at the same time. In particular, the values-based mission of the social enterprise, closely aligned with that of the nonprofit parent, acted to balance the divergence and convergence dynamics involved in generating a legitimate social enterprise. For example, while Ako Books had a strong drive to make profit, and legal separation enabled more rapid business decisions than was possible in their parent organization, they remained committed to publishing books that supported Playcenter philosophy on parenting and play. Similarly, Lifewise's commitment to community integration for homeless people and Changeability's drive to improve mental wellness in the wider community motivated the development of new skills that were difficult to acquire in a nonprofit environment.

The values-based mission acted as an 'anchor' for the enterprise, supporting reconciliation of the capabilities both possessed and needed. Embedding the social enterprise activity into the mission of the parent organization increased legitimacy and active support for the new income-generating endeavor. Purpose and profit aligned were more attractive to the nonprofit and its personnel than if undertaken separately.

Conclusions and limitations

Nonprofits are critical to the growth of the social enterprise sector and yet relatively little is known about the development of these hybrid organizations within this context. This research provides further insight on the introduction and accommodation of a social enterprise within a nonprofit. Using the structural attractor concept, the model expands the work of a number of complexity writers into the specific context of social enterprise within a nonprofit (Allen et al., 2011; Goldstein et al., 2008; Hazy, 2011). The challenges of social enterprise development in nonprofits is discussed with writers on social enterprise and nonprofits (Billis, 2010; Dees, 2012; Young & Kim, 2015) in complexity theory terms. Specifically, this theoretical contribution also increases practitioner understanding of the introduction and accommodation process by outlining the commonalities the nonprofits experienced in their management of the social enterprise's business model.

Combining complexity theory with business models has resulted in a conclusion that the business model can act as a structural attractor, linking the key components conceptually and helping to both generate and reflect the characteristics and capabilities of the social enterprise (Allen et al., 2007; Surie & Singh, 2013). The business model identifies, reflects and aligns the core components of the business and drawing activity towards it, as learning within the social enterprise occurs. There are some business model components that are easier to execute than others, deepening the attractor basin. Identifying and relating to customers or organizing activities, for example, were part of core business for all three nonprofits and therefore there was existing internal competency, aligning these aspects of the business with the larger organization. If new capabilities most required by commercial business models in nonprofits are not provided, this can make the attractor basin shallower and therefore less stable. These include sales and marketing, costing and pricing individual goods and services, general commercial and sectoral expertise and management of higher levels of uncertainty. The novelty of these skills required changes in personnel, internal systems and approaches that stretched the capability of the social enterprise and wider organization in all three cases. In particular in Ako Books and Merge Café, this extended to significant restructured and the creation of entirely new operational systems. The values-based mission acts as an anchor that unifies these and reminds the system of the essential social purpose for which the commercial activity exists. With some supporting empirical data, seeing the business model as a structural attractor contributes to the academic conversation around this topic. For example, raising the price of food for the homeless by one dollar was seen in the context of the perceived importance of reciprocity.

Theory surrounding the complexity concept of structural attractors is still at an early stage of development and further research is needed on how many might co-exist in an organizational setting such as nonprofits, how they interact, and how their qualities might be presented visually.

While offering a fresh examination of how nonprofits develop social enterprises, this study is subject to several limitations. The focus on organizations in one country means that the findings need verification in other contexts. And the small sample size means the research is exploratory in nature. Future studies could focus on a more heterogeneous selection of nonprofits, including smaller and very large organizations to see if the findings remain consistent across a wider range of organizations. Seeking only an internal perspective of the social enterprise development, the research largely ignored the wider environment, including the views of funders, customers and clients, and did not fully address the competitive environment.

References

Allen, P.M. (2001a). "A complex systems approach to learning in adaptive networks," International Journal of Innovation Management, ISSN 1363-9196, 5(2): 149.

Allen, P.M. (2001b). "What is complexity science? Knowledge of the limits to knowledge," Emergence, ISSN 1521-3250, 3(1): 24-42.

Allen, P.M., Maguire, S. and McKelvey, B. (eds.) (2011). The SAGE Handbook of Complexity and Management, ISBN 9781847875693.

Allen, P.M., Strathern, M. and Baldwin, J. (2007). "Complexity and the limits to learning," Journal of Evolutionary Economics, ISSN 0936-9937, 17(4): 401-431.

Alter, K. (2009). "The four lenses strategic framework: Toward an integrated social enterprise methodology," link.

Battilana, J. and Dorado, S. (2010). "Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations," Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, ISSN 0001-4273, 53: 1419-1440.

Battilana, J. and Lee, M. (2014). "Advancing research on hybrid organizing: Insights from the study of social enterprises," The Academy of Management Annals, ISSN 1941-6520, 8(1): 397.

Billis, D. (ed.) (2010). Hybrid Organizations and the Third Sector: Challenges for Practice, Theory and Policy, ISBN 9780230234635.

Brourad, F. and Lavriet, S. (2010). "Essay of clarifications and definitions of the related concepts of social enterprise, social entrepreneur and social entrepreneurship," in A. Fayolle & H. Matlay (eds.), Handbook of Research on Social Entrepreneurship, ISBN 9781848444270.

Bryman, A. and Bell, E. (2003). Business Research Methods, ISBN 9780199259380.

Daft, R. (1983). "Learning the craft of organizational research," The Academy of Management Review, ISSN 0363-7425, 8(4): 539.

Dart, R., Clow, E. and Armstrong, A. (2010). "Meaningful difficulties in the mapping of social enterprises," Social Enterprise Journal, ISSN 1750-8614, 6(3): 186-193.

Dees, J.G. (2012). "A tale of two cultures: charity, problem solving, and the future of social entrepreneurship," Journal of Business Ethics, ISSN 0167-4544, 111(3): 321-334.

Defourny, J. and Nyssens, M. (2008). "Social enterprise in Europe: recent trends and developments," Social Enterprise Journal, ISSN 1750-8614, 4(3): 202.

Defourny, J. and Nyssens, M. (2010). "Conceptions of social enterprise and social entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and divergences," Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, ISSN 1942-0676, 1(1): 32-53.

Denzin, N.K. (2002). "The interpretive process," in A.M. Huberman & M.B. Miles (eds.), The Qualitative Researcher's Companion, ISBN 9780761911913, pp. 349-366.

Department of Internal Affairs (2013). Mapping social enterprises in New Zealand: Results of the 2012 social enterprise survey, link.

Eisenhardt, K. (1989). "Building theories from case study research," The Academy of Management Review, ISSN 0363-7425, 14(4): 532.

Emerson, J. (2003). "The blending value proposition: Integrating social and financial returns," California Management Review, ISSN 0008-1256, 45(4): 35.

Folke, C., Carpenter, S.R., Walker, B., Scheffer, M., Chapin, T. and Rockström, J. (2010). "Resilience thinking: Integrating resilience, adaptability and transformability," Ecology and Society, ISSN 1708-3087, 15(4).

Foster, W. and Bradach, J. (2005). "Should nonprofits seek profits?" Harvard Business Review, ISSN 0017-8012, 83(2): 92.

Galaskiewicz, J. and Barringer, S.N. (2012). "Social enterprises and social categories," in Y. Hasenfeld & B. Gidron (eds.), Social Enterprises: An Organizational Perspective, ISBN 9781137035301, pp. 47-70.

Gibbons J. and Hazy J.K (2017). "Leading a large-scale distributed social enterprise: How the leadership culture at Goodwill Industries® creates and distributes value in communities," Nonprofit Management and Leadership, ISSN 1048-6682, 27(3): 299-316.

Goldstein, J., Hazy, J.K. and Silberstang, J. (2008). "Complexity and social entrepreneurship: A fortuitous meeting," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 10(3): 9-24.

Goldstein, J., Hazy, J.K. and Silberstang, J. (eds.) (2009). Complexity Science and Social Entrepreneurship: Adding Social Value through Systems Thinking, ISBN 9780984216406.

Haigh, N., Walker, J., Bacq, S., & Kickul, J. (2015). "Hybrid organizations: Origins, strategies, impacts, and implications," California Management Review, ISSN 0008-1256, 57(3): 5-12.

Hazy, J.K. (2008). "Toward a theory of leadership in complex systems: Computational modeling explorations," Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, ISSN 1090-0578, 12(3): 281.

Hazy, J.K. (2011). "More than a metaphor: Complexity and the new rules of management," in P. Allen, S. Maguire & B. McKelvey (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Complexity and Management, ISBN 9781847875693, pp. 524-540.

Hazy, J.K. and Backström, T. (2013). "Human interaction dynamics (HID): Foundations, definitions, and directions," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 15(4): 91-111.

Kerlin, J. (2010). "A comparative analysis of the global emergence of social enterprise," Voluntas, ISSN 0957-8765, 21(2): 162-179.

Kirkman, D. (2012). "Social enterprises: An multi-level framework of the innovation adoption process," Innovation: Management, Policy & Practice, ISSN 1447-9338, 14(1): 143.

Lythberg, B.J., Woods, C. and Henare, M. (2015). "The Maori marae as a structural attractor," Academy of Management Proceedings, ISSN 0065-0668, 1: 15398.

Mackenzie, A. (2005). "The problem of the attractor: A singular generality between sciences and social theory," Theory, Culture & Society, ISSN 0263-2764, 22(5): 45.

Maguire, S. (2011). "Constructing and appreciating complexity," in P. Allen, S. Maguire & B. McKelvey (eds.), The Sage Handbook of Complexity and Management, ISBN 9781784021290, pp. 79-93.

McGrath, R.G. (2010). "Business models: A discovery driven approach," Long Range Planning, ISSN 0024-6301, 43(2-3): 247-261.

Morris, M.H., Coombes, S., Schindehutte, M. and Allen, J. (2007). "Antecedents and outcomes of entrepreneurial and market orientations in a non-profit context: Theoretical and empirical insights," Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, ISSN 1548-0518, 13(4): 12.

Morris, M.H., Schindehutte, M., & Allen, J. (2005). "The entrepreneur's business model: toward a unified perspective," Journal of Business Research, ISSN 0148-2963, 58(6): 726.

Oster, S.M., Massarsky, C.W. and Beinhacker, S.L. (eds.) (2004). Generating and Sustaining Nonprofit Earned Income: A Guide to Successful Enterprise Strategies, ISBN 9780787972387.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. and Clark, T. (2010). Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers, ISBN 9780470901038.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y. and Tucci, C.L. (2005). "Clarifying business models: Origins, present, and future of the concept," Communications of the Association for Information Systems, ISSN 1529-3181, 16: 1.

Peattie, K. and Morley, A. (2008). "Eight paradoxes of the social enterprise research agenda," Social Enterprise Journal, ISSN 1750-8614, 4(2): 91-107.

Perrini, F. and Vurro, C. (2006). "Social entrepreneurship: Innovation and social change across theory and practice," in J. Mair, J. Robinson, & K. Hockerts (eds.), Social Entrepreneurship, ISBN 9781403996640, pp. 55-86.

Plowman, D.A., Baker, L., Beck, T.E. and Kulkarni, M. (2007). "Radical change accidentally: The emergence and amplification of small change," Academy of Management Journal, ISSN 0001-4273, 50(3): 515.

Rhodes, M.L. and Donnelly-Cox, G. (2008). "Social entrepreneurship as a performance landscape: The case of 'Front Line'," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 10(3): 35-50.

Russell, L. and Duncan, S. (2007). "Social enterprise in practice: Developmental stories from the voluntary and community sectors," link.

Shepherd, D. and Woods, C. (2011). "Developing digital citizenship for digital tots: Hector's World Limited," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 13(3): 1-20.

Smith, W.K., Besharov, M.L., Wessels, A.K. and Chertok, M. (2012). "A paradoxical leadership model for social entrepreneurs: Challenges, leadership skills, and pedagogical tools for managing social and commercial demands," Academy of Management Learning & Education, ISSN 1537-260X, 11(3): 463-478.

Surie, G. and Singh, H. (2013). "A theory of the emergence of organizational form: The dynamics of cross-border knowledge production by Indian firms," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 15(4): 37-75.

Swanson, L.A. and Zhang, D.D. (2011). "Complexity theory and the social entrepreneurship zone," Emergence: Complexity & Organization, ISSN 1521-3250, 13(3): 39-56.

Trivedi, C. and Stokols, D. (2011). "Social enterprises and corporate enterprises: Fundamental differences and defining features," Journal of Entrepreneurship, ISSN 0971-3557, 20(1): 1-32.

Tsoukas, H. (1998). "Introduction: Chaos, complexity and organization theory," Organization, ISSN 1350-5084, 5(3): 291-313.

Uhl-Bien, M. and Marion, R. (2008). Complexity Leadership, ISBN 9781593117955.

Young, D.R. (2001). "Organizational identity in nonprofit organizations: Strategic and structural implications," Nonprofit Management & Leadership, ISSN 1048-6682, 12(2): 139.

Young, D.R. and Kim, C. (2015). "Can social enterprises remain sustainable and mission-focused? Applying resiliency theory," Social Enterprise Journal, ISSN 1750-8614, 11(3): 233-259.

Young, D.R., Searing, E.A.M., Brewer, C.V. and Edward Elgar, P. (2016). The Social Enterprise Zoo: A Guide for Perplexed Scholars, Entrepreneurs, Philanthropists, Leaders, Investors and Policymakers, ISBN 9781784716066.