Mergers versus Emergers

Structural Change in Health Care Systems

Brenda Zimmerman

McGill University, USA

Kevin Dooley

Arizona State University, USA

Introduction

Mergers and acquisitions accounted for several hundred billion dollars in transactions in the US and Canada in 1999 (Irving Levin Associates, 2000). In the health care sector and in general, they are one of the most popular and influential forms of discretionary business investment (Sirower, 1997). Hospital merger activity peaked in 1997 (Bellandi, 1999). Specifically in the hospital sector, between 1995 and 1997, 169 transactions involving 325 hospitals took place, with a market value of $18 billion. Overall, 713 deals encompassing $21 billion occurred in health care in 1999 in the US. (Irving Levin Associates, 2000). It is estimated that some 10-15 percent of health care organizations have entered into a merger arrangement of some form, with non-profit hospitals being especially active (Connor et al., 1997). Mergers in particular are common, for example, between regional hospitals, or between hospitals and physician groups. Other types of structural change include acquisitions, strategic alliances, networks, coalitions, and sharing of information, technology, and markets.

In current business practice the basic purpose of a merger or acquisition is to improve the sustainability of the corresponding organizations by bringing together resources and knowledge for the benefit of providing improved profit and/or reduced price through reduced cost and/or improved revenue. Resources that are a focal point of mergers include physical assets such as buildings, equipment, and capacity, financial assets such as cash, revenue, and reserves, human assets such as staff and management, operational assets such as business processes and information systems, and market assets such as insurers and consumers. Knowledge, although less tangible, can also be a focal point of a merger. For example, a hospital may be interested in the specialty services that a particular clinic can provide.

In this article we first view hospital mergers and other structural change through the lens of the currently dominant, mechanistic business model of health care, and find that structural change is a rational response to market pressures. We will present a mechanistic model that pinpoints where hospital mergers have focused their attention and why. We next present a biological model inspired by complexity science that illustrates the broader, explorative role that mergers based on the principles of self-organization could have.

MERGERS: A MECHANISTIC VIEW

A prototypical example of a large-scale hospital merger that is considered to be successful is the BJC Health System in St. Louis (Bitoun, 1998). The merger began in 1992 as an affiliation between two teaching hospitals; in 2000 it was a regional system with 14 hospitals, six nursing homes, and a health plan, generating nearly $1.6 billion in revenues and a third of the market. Benefits have included $116 million in savings from operations via consolidation of business processes, support services, and purchasing. There was also increased patient access to highly trained specialists, advanced research, and outreach to more HMO (Health Maintenance Organization)1 patients. Leverage has also improved, as BJC and its 2,000 doctors were bargaining collectively with managed care plans.

There are numerous examples of not-so-successful couplings, however. The merger between UCSF and Stanford research hospitals resulted in a loss of $11 million in the fourth quarter of 1998, and was expected to lose $60 million by the end of 1999. Key problems included lack of involvement of key managers during merger discussions, poor information and reporting systems, and a slumping market. In March 1999, the health care network announced that about 2,000 jobs would be eliminated, about 900 through layoffs.

The research on hospital mergers (Connor et al., 1997) shows that on average, some modest performance improvements in utilization, elimination of duplicated services, and cost saving can be obtained, but the evidence is mixed. Some studies confirm that health care mergers lead to a reduction in cost; others find that mergers reduce variation in demand volume; and some studies support and others refute the proposition that mergers lead to reduced price. In one of the more comprehensive studies, Connor and colleagues examined changes in costs and prices for 3,500 acute care hospitals in the US from 1986 to 1994 and 122 mergers of 244 hospitals. Investigators reported that the mergers, generally beneficial, produced price reductions of 7 percent on average. In markets with high penetration by HMOs mergers produced greater price reductions. Savings were also greater for low-occupancy hospitals, non-teaching hospitals, non-system hospitals, similar-size hospitals, and hospitals with more duplicated services before the merger.

However, the health care industry in North America has many stories of failed mergers, in terms of either the merger failing to achieve the goals intended or the merged entities failing to stay together. Sirower's (1997) study of 300 hospital mergers concluded that few consolidate more than administrative functions. In a 2000 study of 467 multi-hospital systems in the US, 34 percent reported losses from operations compared to 21 percent in 1999. The study showed an increase of “disintegration” of some or all of the merged systems; 41 percent of respondents reported that they were considering or had recently experienced disintegration in their system (Arista Associates & Modern Healthcare, 2000).

With such potential for a disastrous outcome and such a marginal probability of success, why do health care organizations merge? Mergers and other forms of structural change are adaptations; the perspective of the current paradigm, however, may limit the repertoire of changes considered (Kuhn, 1970). Therefore we argue that the best way to understand the answer to the question “Why merge?” is to examine that question through the “lens” that mimics the manner in which most modern health care managers and executives view their business.

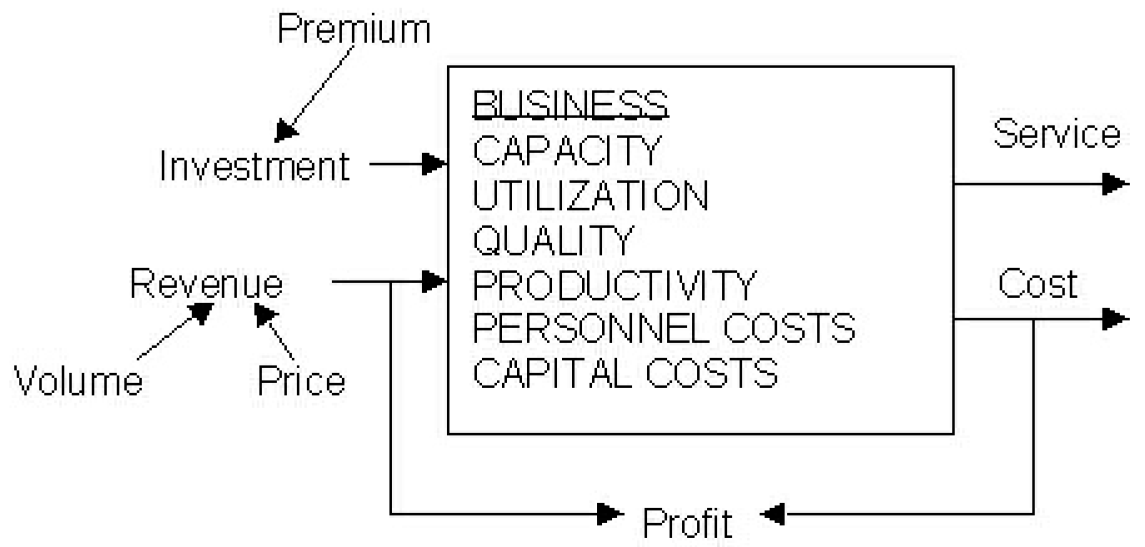

Within a reductionist scientific management paradigm, the system is conceptualized as a “machine”—something that takes inputs and transforms them in some manner into outputs. Such a model is depicted in Figure 1. Revenue either from consumers or investors flows into the health care system and is used to produce services. The operation of the business results in a particular level of costs. Costs and revenues combine to determine profit. Even in a non-profit setting, the tradeoff of costs and revenues is crucial for survival. Non-profit hospitals usually need at least a breakeven bottom line in order to thrive. Revenues from consumers are dependent on the volume of services demanded and the price charged. There are more complex, economic linkages between cost, price, and volume not depicted here. Profits may be taken or may (in part or whole) be reinvested in the system. Service outcomes are determined by the quality, productivity, capacity, utilization, and cost of the clinical and business processes that make up the organization. Overall costs are determined by the variable costs of running these processes, and by the fixed costs associated with personnel, capital equipment, and physical plant.

Figure 1 A mechanistic model of a health care business

Seen through such a lens, mergers and other structural changes are a rational response to changes in the environment; namely, pressures to reduce price while maintaining breadth of coverage and quality of service. These pressures are coming from many sources, including purchasers of health care such as major employers and business coalitions (Campbell, 1997), the government and HMOs through reduced compensation and increased capitation, and the ever-increasing cost of pharmaceuticals (Iglehart, 1999). As the margin between cost and revenue decreases, costs must be reduced (or revenues increased) in order to maintain viability. Competition exists because of the still lucrative potential of the industry, luring investors and thus organizations into the market.

To some extent, health care organizations have already picked the “low-hanging fruit” that has led to improvement in the quality and productivity of their clinical and business processes. Quality has been the focus of TQM efforts in which hospitals have widely engaged since the 1980s (Westphal et al., 1997). Productivity improvement has mainly been targeted through the use of technology, especially information technology. Now that quality and productivity improvements are harder to realize, the question remains of how to reduce costs and thus maintain profit (or in the case of non-profits, minimize the risk of a deficit), since market pressures do not appear to allow either an increase in price or demand volume. Quality and productivity improvement efforts produced some cost reductions; mergers are the next logical step.

Once again, as seen through the lens of the mechanistic model, a merger can attain the following benefits (Lynk, 1995):

- Capacity can be “right-sized” (increased or decreased), according to market needs.

- Through consolidation and capacity reconfiguration, utilization rates can increase.

- Other cost advantages can be obtained through consolidation of clinical and business processes, taking advantage of economies of scale.

- Erosion of prices leads directly to erosion of profit. In order to maintain some control over prices, health care systems have sought to increase in size.

- Closing down certain facilities and opening up others is considered a logical means to maintain maximum volume of demand, especially in areas where population densities are rapidly changing.

- Lynk's (1995) study documented merger savings achieved by reduced variation in service demand by pooling services.

- Especially in acquisition situations, a premium price may be paid that serves as an influx of cash (investment) into the organization.

How did this economic view of merger necessity take hold in the health care sector? In large part it is a result of a change in ideology vis-à-vis government's role that was established by the early 1980s in the UK, the US, and to a lesser extent Canada and other western countries (Estes & Alford, 1990; Kitchener, 2000). The ideology has two main tenets: first the primacy of the market to justify government spending; and second the concept of individualism suggesting the need for significantly less government. This played out in the health care sector by redefining health as an economic good and promoting professional managers as opposed to clinicians to lead health care organizations (Kitchener, 2000). Professionally trained managers in the early 1980s, and to quite an extent today, are trained in models of transaction cost analysis and other efficiency approaches. Analysis of the health care sector from this perspective leads to a logical conclusion of the economic necessity of mergers. Although economic necessity is often cited as the rationale for a merger, some researchers have argued that the increased attention to mergers and joint ventures may be as much a fashion trend as anything else (Kogut, 1988). There is also evidence that mergers are undertaken to increase the senior management's team control over an industry (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983).

In a broader context, mergers in health care do not question the legitimacy of the mechanistic model, nor of the basic assumptions of “existence” behind the mechanistic model; there is no questioning of health care fundamentals (Christensen et al., 2000). Mergers are not intended to challenge who delivers health care, how it is delivered, or what health care is primarily about. The expectations of mergers are to “save health care” as if the real issue is how to keep the system the same with less money. In other words, mergers can be seen as an adaptive response to maintain the status quo.

A COMPLEXITY PERSPECTIVE ON MERGERS

Complex systems are highly historical; the best way to understand the present is to examine the past. History shapes individual and organizational schema (mental models, or “world-view”) and schema in turn constrain what is seen and not seen, what is important and what is not. By understanding history, we can see how current participants might view the world around them.

The history of modern health care, as practiced in the twentieth century, is primarily a story about hospitals and doctors. Doctors showed that through careful application of the scientific method, disease and illness could be treated in a rational and consistent manner. So successful was this model that a health care system defined by the presence and authority of doctors and hospitals quickly became dominant. Vogel (1980) commented, “The contemporary hospital has assumed different forms in different places, but it is a product of a modern medicine in a modern society.” The hospital organization was influenced by the same modes of thought and action (reductionism, determinism, separation of knowing from doing, bureaucratic hierarchical management structures) that affected all business enterprises during the (early) twentieth century (Dowd & Tilson, 1998).

Reductionism is the belief that systems can be best understood, and optimized, through depicting a system by its parts and describing and optimizing the parts. Reductionism enacts itself in modern health care in some of the following patterns:

- Physicians as independent contractors.

- Disease/parts specializations as more prestigious than generalists.

- Hospitals as fortresses: Knowledge kept inside, patients have to come to hospital.

- Hospitals as stand-alone entities—“in” communities but not “of” communities.

Health care is different from other industries, however, because of the very nature of its business, being a steward of human life. Early on doctors were rigorous in their self-monitoring and self-legitimation (Peirce, 2000). Licensing procedures were implemented and medical science knowledge institutionalized within medical schools and their training regimens. New doctors were required to go through extensive in-field mentoring with the elders of the discipline. This further reinforced the beliefs and norms of the discipline of health care as health science. As Walls and McDaniel (2000) relate, the professional disciplines of health care “inculcated students with certain attitudes and values that influenced their behavior … Healthcare organizations are often considered to be the premier example of professional organizations. However, they are unique in that they house several sets of professionals (disciplines) within one organization.”

The hospital is both embedded in and representative of our society, but also somewhat disconnected. The concept of reductionism so dominates thinking that the hospital itself separates from the rest of society. Recently there has been increased awareness among hospital clinicians of the broad determinants of health. The impetus for this broadening perspective—to show the embeddedness of economic, social, psychological, spiritual, and physical health at all scales (individual, family, society)—did not originate from the hospital/health care sector. The hospital has become the epitome of the lack of connectedness that is indicative in other elements of our society. Ironically, the more we become connected, the more disconnected we also become.

The discipline of health science directs the unconscious way in which physicians define science, health, and their work, which in turn shapes their institutions. Hospitals reflect the science of the physicians, an inward focus or focus on the parts and the mystery of the parts, which is not accessible to others. Hence patients become more ignorant of health as they enter the hospital because they (complicitly) abandon the notions of connectedness and systems thinking to worship at the science of the “parts.” “Fixing the parts will fix the whole” is the mantra of those working in hospitals, of the hospitals themselves, and of the patients who use the hospitals.

In a larger context, this also reflects the objective science notion of positivism, which is dominant in health science. The researcher can be outside of the system and manipulate it without being “of” the system.

Medical approaches to health and the hospitalization of health care exemplify this assumption. Many individuals feel that this is “good science” and are highly suspect of subjective data, context-specific solutions (pejoratively called anecdotal evidence), and so on.

Seen in this light, mergers and other structural changes represent a further entrenchment of the status quo assumptions. How long can this reasoning go unchallenged? As health care broadens (as it has) to include more of an emphasis on prevention and wellness, embeddedness will (and must) be re-established. A move toward embeddedness and away from isolation is also observed as “health science” knowledge becomes more widely accessible by consumers through the internet, thus shifting the basic business model of modern health care.

The paradigm of health care is also shifting in some segments of the system. Recent studies of women, the major users of the health care system, indicate that women's view of health is much more relationship based than “parts” based (Reed et al., 2000). Relationships are not seen as a mere component of health but as the key determinant of health and wellbeing. From this perspective, the current health care system, which is built on concepts of autonomy and independence (both clinically and professionally), would also need to change. A relationship-focused concept of health requires a health care system that both values and utilizes relationships as central to the work. Rather than individuals or even individuals and their environmental system, as seen in the social ecology literature, the primary agents of a relational being health care system are relationships of all kinds (Reed et al., 2000)

Consider the following provocative proposition. As the health care system naturally evolves away from a paradigm of isolation to a paradigm of embeddedness, this diminishes the perceived and/or real power of hospitals. In order to deal with this loss of power, they look to other forms of legitimacy. What is the overwhelming characteristic of the huge majority of structural changes that have taken place? They are all about one thing: size. Mergers and other structural changes primarily focus on being bigger—since this is the best way to do what you are already doing better—rather than changing the nature of health care delivery. Hence we could view it as avoidance behavior, which will likely have limited impact. In fact, our previous discussions demonstrate that structural changes in health care have excelled at maintaining the status quo in all but some administrative functions.

So in summary, mergers and structural changes are about maintaining the status quo of reductionism or economies of scale, but in a thin sense rather than a deepening sense of the connectedness of health, environments, and individuals. Alternatively, a complexity perspective on the situation would focus on relationships, connections, rules of interaction, and mental models.

EMERGERS: SYNERGY AS AN EMERGENT PHENOMENON

Modern managers often view synergy as something that is deterministic, and thus can be created and managed. This is not wrong: Synergy can be deterministic in the sense that it is an outcome for which actions can be selected, planned, and executed. That is not the only type of synergy that is possible, however. Consider the definitions of the words emergence and synergy (from Merriam-Webster's online dictionary):

Synergy: “a mutually advantageous conjunction or compatibility of distinct business participants or elements (as resources or efforts).” Emergence: “the act of becoming manifest, coming out into view, rising from an obscure or inferior position or condition, or coming into being through evolution.”

Mergers and other structural changes are supposed to create synergy, but more often than not they fail to meet the requirements of the definition. They are not necessarily between distinctly different participants, and they are not always mutually advantageous; rather, it is typical for almost identical participants (e.g., hospitals) to merge and/or for one partner in the structural change to see much more advantage than the other.

We can have intended or emergent synergies just as we can have intended or emergent strategies (Mintzberg, 1987). In spite of best intentions, synergies are often not realized in mergers in all industries (Sirower, 1997). From a complexity science perspective, the unrealized intentions are often due to hidden attractor patterns. Implicit mental models or interpretive schema maintain the status quo even when the stated intentions are to change. Using the same logic, emergent synergies can be created when different mental models interact and individuals or groups start to see how they carry a mindset that affects what they see, how they see, and therefore what changes are really viable.

Mintzberg and Glouberman (2000) argue that it is more difficult in health care than in other industries to reveal and change mindsets. Because of the high level of specialization within medicine, mindsets are divided and become a major roadblock to change. They point out two aspects of health care that indicate latent potential for integration and hence synergies. First, health care workers—whether doctors, nurses, administrators, or trustees—are drawn to health care for similar reasons. There is a shared overall sense of altruism or purpose as well as a desire to advance knowledge and an interest or ability to deal with crises or urgent care situations. Mintzberg and Glouberman also argue that although the sharing of perspectives and cooperation is rare at an institutional level in health care, there is evidence that cooperation and mutual adjustment are the norm in many aspects of the clinical world. Informal communication and cooperation are crucial in many clinical contexts. So this suggests a more optimistic picture for health care systems. There is both a purpose dimension and a skill set that can be drawn on to enhance synergies in mergers and radically alter the way health care is defined and delivered.

That said, the type of synergy that is created by most mergers and other structural changes is via economies of scale, a concept that only has meaning in the context of continuing to do the same things that one is already doing. This deterministic synergy is about maintaining the current business model, but performing better within it. Thus deterministic synergy is aimed at exploiting existing knowledge, assumptions, and values.

If we allow the possibility that the modern health care system and its associated business model are either primed for evolution to some other more effective form, or inferior to other possible configurations, then it is possible to entertain the notion of emergent synergy. Since the word merger is so often used to define the activities that lead to what we have referred to as deterministic synergy, we would like to introduce a new term that defines the activities that lead to what we define as emergent synergy: emerger.

An emerger is the act of two or more organizations coming together for the purpose of allowing synergy to evolve naturally from within. Emergent synergy comes about through the processes of self-organization, which is (Goldstein, in Zimmerman et al., 1998) “a process . . . whereby new emergent structures, patterns, and properties arise without being externally imposed on the system.” Self-organization occurs through the aggregation of local agents operating in local environments with local information; in other words, self-organization is about organization from the bottom up as opposed to the top down. Key to self-organization is seeing it as a pattern of relationships rather than a pattern of parts. The connections and connectedness are the primary source of self-organizing capacity. Emergent patterns cannot be predicted ahead of time; the system must be allowed to evolve and such patterns will become known over time. Emergent patterns also have a scalar quality in that what happens at the local level is seen also at the global level. The patterns repeat at all scales, not to create exact replicas but to create an overall coherence.

Now, consider how a manager might think about mergers and synergy if in fact their mental model of the business of health care was organic as opposed to mechanistic. First, we note that the conventional merger focus—resources—is still also a component of the complexity perspective. In an emerger, however, we allow for synergy through resource aggregation to evolve in a somewhat unpredictable fashion over time. This is common in business in general, but very uncommon in health care.

For example, while IBM's acquisition of Lotus could be construed as an acquisition of the (then lucrative) Lotus Notes product, it really was an acquisition of core competencies in the area of corporate intranet software. IBM cannot predict exactly what will come of the coupling between expertise in corporate intranets and its own core competencies, but it has bet that something valuable will emerge. Even more indicative is the (e)merger between AOL and Time Warner. While neither is sure how the next five years of convergence between telephony, cable, the internet, and entertainment will end up, they are betting that synergies between content providers and access providers will emerge.

In both cases we see diversity in the coupling partners. IBM has expertise in hardware that couples with Lotus's expertise in software. AOL's internet and electronic networking skills are in contrast to Time Warner's print media skills. Different industry backgrounds provide an opportunity to challenge status quo assumptions and to co-create new industries. In most health care mergers in the US and Canada the differences between coupling partners are relatively minor and hence existing assumptions about health care remain unchallenged—and frequently unnoticed.

A complexity model also emphasizes the connectivity between agents, as a means to facilitate the flow of resources and knowledge (Walls & McDaniel, 2000). Such a perspective perhaps shifts emphasis away from mergers and acquisitions per se, and toward networks and coalitions. Cooperative and collaborative agreements between organizations may provide many of the synergistic benefits of a more complete coupling, but may be much less risky (Eisenhardt & Galunic, 2000).

Geriatric health care tends to show more of this web-like cooperation. Geriatric health issues frequently require social and environmental factors to be addressed as well as acute and chronic physical health need. Doctors and nurses frequently consult with families or support agencies to identify various means of supporting a senior's multifaceted needs.

As more and more of our health care needs are multi-dimensional such as geriatrics, the need for more and more cooperative modes of interacting at all levels in the system will grow (Mintzberg & Glouberman, 2000). This emphasis on connectivity also leads to creativity concerning who is connected to whom. For example, conventional mergers and acquisitions consider coupling between business entities; the complexity perspective reminds us that couplings between business entities (such as hospitals or HMOs) and other entities, such as government agencies, community groups, and even technology companies, can be equally important.

A complexity model suggests that during an emerger there could be consideration of different types of “fitness measures”; what might have defined “success” for the organizations prior to the emerger may not be relevant after it. For example, health care before the twentieth century emphasized three components of health: physiological, psychological, and spiritual (Starr, 1982). Today's dominant fitness measures in the health care sector only consider the physiological; the psychological is informally wholly the responsibility of the nursing profession, even if formally it is the realm of the psychiatrist or psychologist. The other aspects of relationship health—social, spiritual, or community—are rarely considered to be part of the focus of health care in the hospital-centric health care system.

Finally, a complexity perspective positions us to question the schema that agents possess, and this in turn may raise questions about the boundaries of the existing systems, and even existing assumptions. For example, an emerger might question the following types of assumptions:

- Hospitals and doctors are the primary source of health care.

- Find the organization structure that works and stick with it.

- Physicians should be key decision makers in the allocation of resources.

- The “scientification” of health care has limitless potential.

- Health care needs to be “provided,” implying the need for a distinction between “providers” and “consumers.”

- Extension of life should occur at all costs.

- Health care and other government functions such as policing, fire fighting, and environmental safety represent separate missions.

- Health is primarily about the human body.

- Health is best achieved by improving the health of human organs.

All of these assumptions have been challenged in pockets of the broader health care system. But because they don't fall under the normal schema, they are often not “seen” as health care or are dismissed as less relevant to the “real work” of health care.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we believe that emergers and the subsequent emergent synergy that evolves could provide two significant benefits. First, these emergers could focus on more than merely reducing costs. While mergers and acquisitions in other industries often focus on innovating new lines of business in an adaptive and emergent fashion (Carey, 2000), we see very little innovation of that sort within health care; what there is often either comes from outside of the industry's usual participants, or is at the fringes of legitimacy within the industry. Meditation and acupuncture, which are now considered to be more mainstream health care approaches (White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy, 2002), were not only not initiated by health care professionals but also were for many years dismissed as “non-scientific” and by extension of little value in improving health (Angell & Kassirer, 1998).

Second, emergers could be used to innovate radically different configurations of our health care system. Revisiting the differences that we outlined at the beginning of the article between the traditional and complexity perspectives yields some insights about both the expectation and the execution of mergers. Table 1 highlights some of the implications of the complexity perspective. The last column raises questions about whether mergers are an appropriate response to the current challenges in the health care industry. One of the most significant contributions of complexity science here is not prescriptive but descriptive. The real power is its ability to shine a light on how things are really happening rather than how we would like them to happen. It forces us to relinquish some of our illusions. Given the huge amount of resources that are invested in mergers in health care each year, it seems prudent to step back and ask which issues can really be solved by mergers and which can be hindered by them. It asks us to pay attention to factors that under a traditional lens are deemed to be less important.

| TRADITIONAL PERSPECTIVE | COMPLEXITY PERSPECTIVE | IMPLICATIONS OF CHANGING PERSPECTIVE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nature of synergy | Synergy can be deliberately created—it is deterministic | Synergy is an emergent phenomenon | Focuses attention on the emergent synergies to enhance them |

| Source of control | Mergers can increase control over the market by expanding the boundaries of the organization | The environment is not a separate entity or space and hence cannot be controlled by expanding the boundaries The environment is a changing function created by the players themselves | Expands peripheral vision to include other systems and industries that are interacting and shaping health care systems |

| Role of history | Mergers are necessary to deal with changing complex environments Existing organizations can and must be replaced by a new designed organization | Organizations are highly impacted by their history—time is irreversible Paradoxically, history cannot predict the future and yet acts as both enabler and constraint | Implies an important role for awareness of the local histories in an organization and culture, but not as a predictor of future outcomes |

| Nature of organizations | Mergers can be “designed”—by implication, an outside view of the system | Mergers are not “designable” per se—one cannot be outside a complex system and manipulate it to perform in predictable ways | Changes the expectations of predictability Expecting unpredictability is a preparedness strategy |

| Creation and novelty of innovation | Mergers can increase the potential for innovation through knowledge creation | The central source of knowledge creation is in the relationships of an organization | Mergers can diminish the potential for knowledge creation by breaking apart relationships Patching may be more useful |

| Critical costs | Mergers can decrease costs through reduced duplication | The most significant costs in knowledge creation cannot be elimination through reduction of duplication—only the costs that are most clearly mechanistic can easily be reduced in mergers | Outsourcing may be more effective than mergers for the more “mechanistic” costs in a system. For knowledge creation, the nature of relationships and connectedness are key |

Table 1 Revisiting the two views of mergers

In this article we have explored the impact of changing the mindset or metaphor of health care from a machine, based on Newtonian science, to a biological living being, based on complexity science. In particular, we have looked at how the two mindsets alter the expectations and executions of mergers and system formations.

Hospitals and the focus on health science will not disappear overnight, nor should they necessarily ever disappear. However, we believe that the hospital-centric model, which is the basis for most mergers in the US health care system as in many other countries, is a limiting model. Hospitals and health science radically increased our life span and physical health in the last 100 years. But the returns now to health, life span, and wellbeing are at a stage of diminishing marginal returns. It costs more and more to gain less and less.

The entire [health care] industry has been reshaped by cost-driven mergers and acquisitions. Yet in the last several years, health care costs have continued to escalate at rates in excess of general inflation. (Wasserstein, 1998: 451)

What is needed now is something as radical as the notion of hospitals was at their inception. We believe that a biological approach to system formation inspired by complexity science has the potential to provide us with the appropriate questions to ask, the influential patterns to observe, and insights into how we need to change both our expectations and executions of mergers so that they truly are “emergers.”

To paraphrase Albert Einstein, one cannot solve a problem with the same mindset that created the problem. Mergers, as they are traditionally conceived of in health care, run the risk of trying to solve the problems of health care with the same mental constructs and assumptions that created the problems.

NOTE

- HMOs (Health Maintenance Organizations) are vertically integrated insurance and health care providers including hospitals, clinics, and physician practices. Individuals pay annual fees, either directly or through their employers, to belong to an HMO that then determines which procedures are covered, at what rate, and in which facilities.

References

Angell, M. & Kassirer, J. P (1998) “Alternative medicine: The risks of untested and unregulated remedies,” New England Journal of Medicine, 339: 839-41.

Arista Associates & Modern Healthcare (2000) Survey of Integrated Delivery Systems, http://www.aristaassociates.com/2000IDSSurvey_files/.

Barber, J., Koch, K., Parente, D., Mark, J., & Davis, K. (1998) “Evolution of an integrated health system: A life cycle framework,” Journal of Healthcare Management, 43(4): 359-77.

Baskin, K., Goldstein, J., & Lindberg, C. (2000) “Merging, demerging, and emerging and the Deaconess Billings Clinic,” The Physician Executive, May-June: 20-5.

Becker, C. (2000) “Meet the new boss,” Modern Healthcare, July 10: 3.

Bellandi, D. (1999) “Relax, deal pace slowing,” Modern Healthcare, 29(1): 23.

Bitoun, B. M. (1998) “Size does matter,” Hospital and Health Networks, 72(12): 28-36.

Bradshaw, P, Hayday, B., Armstrong, R., Rykert, L. & and Stoops, B. (1998) “An emergent cellular model for governance,” paper presented at the ARNOVA Conference, Seattle.

Campbell, S. (1997) “Pressure from purchasers is driving merger and acquisition activity in health care,” Health Care Strategic Management, 15(12): 17.

Carey, M. (moderator) (2000) “A CEO roundtable on making mergers succeed,” Harvard Business Review, May-June: 145-54.

Christensen, C., Bohmer, R. & Kenagy, J. (2000) “Will disruptive technologies cure health care?,” Harvard Business Review, Sept-Oct: 102-12.

Connor, R. A., Feldman, R. D., Dowd, B. E., & Radcliff, T. A. (1997) “Which types of hospital mergers save consumers money?,” Health Affairs, 16(6): 62-74.

Denis, J., Lamothe, L. & Langley, A. (2000) “The dynamics of collective leadership and strategic change in pluralistic organizations,” working paper, Center for the Analysis of Public Policy.

DiMaggio, J. & Powell, W. (1983) “The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields,” American Sociological Review, 48: 147-60.

Dooley, K. (1997) “A complex adaptive systems model of organization change,” Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, & Life Science, 1(1): 69-97.

Dooley, K., Durfee, W., Shinde, M., & Anderson, J. (2000) “A river runs between us: Legitimate roles and enacted practices in cross-functional product development teams,” Advances in Interdisciplinary Studies of Work Teams: Product Development Teams, 5: 283-302.

Dooley, K. & Zimmerman, B. (2002) “Exploring structural changes in health care through the metaphor of marriage,” working paper, Arizona State University.

Dowd, S. & Tilson, E. (1998) “Health care's future? Look to the past,” Hospital Management Quarterly, August: 1-7.

Eisenhardt, K. & Galunic, D. C. (2000) “Coevolving: At last, a way to make synergies work,” Harvard Business Review, Jan-Feb: 91-102.

Estes, C. & Alford, R. (1990) “Systematic crisis and the nonprofit sector: Toward a political economy of the nonprofit health and social services sector,” Theory and Society, 19: 173-98.

Goldstein, J. (1994) The Unshackled Organization, Portland, OR: Productivity Press.

Goold, M. & Campbell, A. (1998) “Desperately seeking synergy,” Harvard Business Review, Sept-Oct: 131-43.

Guastello, S. (1995) Chaos, Catastrophe, and Human Affairs, Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gulati, R. (1998) “Alliances and networks,” Strategic Management Journal, 19: 293-317.

Handy, C. (1996) Beyond Certainty: The Changing Worlds of Organizations, Boston: Harvard Business School.

Iglehart, J. (1999) “The American health care system: expenditures,” New England Journal of Medicine, 340(1): 70-6.

Irving Levin Associates (1999) Physician Medical Group Acquisition Report (PMGAR), New Canaan, CN.

Kirchheimer, B. (2000) “Sidestepping the altar,” Modern Healthcare, April 4: 2-14.

Kitchener, M. (2000) “The competing bases of legitimacy in professional bureaucracies: Antecedents, processes and outcomes of academic health centre mergers,” working paper prepared for Commonwealth Fund, Harkness Research Fellows' Final Reporting Seminar, Los Angeles, June 23.

Kogut, B. (1988) “Joint ventures: Theoretical and empirical perspectives,” Strategic Management Journal, 9: 319-32.

Kuhn, T. S. (1970) The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Larsson, R. & Finkelstein, S. (1999) “Integrating strategic, organizational and human resource perspectives on mergers and acquisitions; a case survey of synergy realization,” Organization Science, 10(1): 1-26.

Lewin, R. (1994) Complexity: Life at the Edge of Chaos, New York: Macmillan.

Lynk, W .J. (1995) “Nonprofit hospital mergers and the exercise of market power,” Journal of Law and Economics, 38(2): 437-61.

March, J. G. (1994) A Primer on Decision-Making, New York: Free Press.

McKelvey, B. (1997) “Quasi-natural organization science,” Organization Science, 8: 351-80.

Mintzberg, H. (1987) “Crafting strategy,” Harvard Business Review, Jul-Aug: 66-75.

Mintzberg, H & Glouberman, S. (2000) “Managing the care of health and the cure of disease: Part I and II,” Healthcare Management Review, 26(1): 56-69.

Peirce, J. (2000) “The paradox of physicians and administrators in health care organizations,” Health Care Management Review, 25(1): 7-28.

Reed, K., Kasle, S., & Wilhelm, M. (2000), “Parallel and shifting paradigms: Implications of women's understanding of health and well being,” working paper, Arizona Health Sciences Center/University of Arizona.

Regine, B. (1999) The Hunterdon Medical Center: Critical Mass and the Emergence of the Goddess, Dallas, TX: VHA..

Rosenberg, C. (1987) The Care of Strangers: The Rise of America's Hospital System, New York: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Scott, W.R. & Backman, E. (1990) “Institutional theory and the medical care sector,” in S. Mick (ed.), Innovations in Health Care Delivery: Insights from Organizational Theory, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass: 20-52.

Sirower, M. (1997) The Synergy Trap: How Companies Lose the Acquisition Game, New York: Free Press.

Stacey, R. (1992) Managing the Unknowable, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Starr, P. (1982) The Social Transformation of American Medicine, New York: Basic Books.

Vecchione, A. (1997) “Changing hospital landscape driving growth in integration,” Drug Topics, 141(20): 64.

Vogel, M. (1980) The Invention of the Modern Hospital, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Walls, M. & McDaniel, R. (2000) “Mergers and acquisitions in professional organizations: A complex adaptive systems approach,” working paper, Austin, TX: University of Texas.

Wasserstein, B. (1998) Big Deal: The Battle for Control of America's Leading Corporations, New York: Warner Books.

Westphal, J., Gulati, R., & Shortell, S. (1997) “Customization or conformity? Institutional and network perspective on the content and consequences of TQM adoption,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 42: 366-94.

White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy (2002) Final Report, Chapter 2, Washington, D.C., March.

Wicks, E. K., Meyer, J. A., & Carlyn, M. (1998) “Assessing the early impact of hospital mergers: An analysis of the St. Louis and Philadelphia markets,” http://www.ndpolicy.com/esresearch/Documents/mergersum.html.

Zimmerman, B. (1998) “Improving performance through coevolution with the environment,” in D. Ripley (ed.), Performance Interventions: The Process, Systems and Total Organization Level, Washington: ISPI: 455-77.

Zimmerman, B., Lindberg, C., & Plsek, P (1998) Edgeware, Irving, TX: VHA.