Complexity, Society, and Everyday Life

Pedro Sotolongo

Instituto de Filosofia, CUB

Introduction

It is hardly debatable that contemporary societies are much more than the simple sum of their parts, or that their development unfolds from the dynamics of their own characteristics. Neither can one hold that the future of societies can be predicted, in so far as apparently insignificant and casual events can have very strong influence on future ones. We know today that societies exhibit the systems-like characteristics of self-organized systems far from equilibrium. In other words, societies behave like nonlinear complex systems with a self-organized unfolding. Contemporary societies also have numerous characteristics that can serve as empirical evidence of the presence of social complexity. All of this means that the important question to ask is how better to characterize social complexity as such.

FROM WHERE DOES SOCIAL COMPLEXITY EMERGE?

We ask ourselves the following questions: Which of the numerous features providing empirical evidence of social complexity should we emphasize in making such a characterization? From where does social complexity emerge? From anthropological constants that men and women living in those societies exhibit as individual social subjectivities? From the various social structures that have an objective existence in those societies? From these and those, that is, from social individuals and social structures, thereby repeating with this question, albeit in a new formulation, the old and as yet unresolved dilemma of the correlation between what social scientists call “the micro” and “the macro”?

For the last four years we at the Instituto de Filosofia have been engaged in an endeavor to conceptualize social complexity. This effort has led us to propose what we might call a third-way approach to that old dilemma, one on which the “complexity approach” can shed new light. This third-way approach focuses on the emergence of patterns of complexity in everyday social life (or, more precisely, just “everyday life,” that relatively and paradoxically “unknown territory” of much contemporary social theory). Such patterns of complexity are those characteristic regimes of collective social practices (family, educational, generational, community based, political, classist, religious, gender, racial, ethnic, etc.) through which real, individual men and women in any society become tacitly, or pre-reflexively, involved in authentic networks of social interactions.

It can be shown empirically and theoretically that it is precisely from one or another such pattern of social interactions of everyday life,1—that is, from one or another of those networks of everyday social interactions—that social complexity emerges. In particular, it can be shown how both the above-mentioned objective social structures and individual social subjectivities issue in a parallel and simultaneous manner from such patterns of social interaction of everyday life.

Why can it be said that it is from these that social complexity emerges? Because each one of those regimes of characteristic collective practices of everyday life functions as a true social-dynamical attractor; that is, as a context-sensitive social constraint2 that has at the same time limiting and enabling effects on those engaged in them, thereby generating an overall social network of their correlations.

The “cementing” or “glueing” power of those patterns of social interactions of everyday life (of such networks of everyday social interactions) stems from the mutual social expectations (family, educational, generational, community based, political, classist, religious, gender, racial, etc.) that tacitly or pre-reflexively establish themselves among those involved in those interactions. Issuing top down from the global network of everyday social interactions on each individual involved in that network, those mutual social expectations serve as limits preventing certain behaviors that then tacitly become known as “socially undesirable.” Simultaneously, and in a bottom-up fashion directed from each of those involved in the interactions to the network as a whole, the interactions enable and make possible certain other behaviors tacitly known as “socially desirable.”

COMPLEXITY-GENERATING SOCIAL “AFFORDANCES”

In themselves the above-mentioned mutual social expectations stem from what we call social affordances, specifically social asymmetrical circumstances arising from the practical interactions of men and women involved with their surrounding social environment, within the limits of any given pattern of social interactions. Among the resulting specifically social affordances that are always present among those involved, we have identified at least four that have special “social-complexity-generating” incidence:

- Inequality of circumstances in favor of some (and disfavoring others), in other words empowering or disempowering (power-inducing and power-induced) social asymmetries (family, educational, generational, community based, political, classist, religious, gender, racial, ethnic, etc.).

- Differences in satisfactions and dissatisfactions, in other words desiring (desire-inducing and desire-induced) social asymmetries (family, educational, generational, community based, political, classist, religious, gender, racial, ethnic, etc.).

- Multiplicity of heuristic positionings, in other words epistemic (knowledge-inducing and knowledge-induced) social asymmetries (family, educational, generational, community based, political, classist, religious, gender, racial, ethnic, etc.).

- Multiplicity of enunciative positionings, in other words discursive (discourse-inducing and discourse-induced) social asymmetries (family, educational, generational, community based, political, classist, religious, gender, racial, ethnic, etc.).

These social affordances are characterized by complexity-generating specific social asymmetries that, because of their intrinsic nature, lead (and cannot help but lead) to the social domains defined by power, desire, knowledge, and discourse.3 They thus act as the ingredients of that cementing mixture (as we choose to call it metaphorically) of mutual social expectations with respect to each of the networks of everyday social interactions, or, in other words, with respect to each pattern of social interaction of everyday life. Even more precisely, we could say that these social affordances lead (and cannot but lead) to “local”4 practices of power, desire, knowledge, and discourse (each of which in turn is circularly linked to the others) in which each of us is involved (and cannot help being involved) in his or her everyday life.

PARALLEL AND SIMULTANEOUS OBJECTIVATION AND SUBJECTIVATION OF OUR PATTERNS OF SOCIAL INTERACTIONS IN EVERYDAY LIFE

In our latest work, Social Theory and Everyday Life: Society as a Complex Dynamical System (which we hope can be published soon), we discuss how objective social structures (which we call the “macro-social”) are produced, and how individual social subjectivities (which we call the “micro-social”) are constructed. In this work we argue that this production and construction take place as parallel and simultaneous processes of collective social objectivation (that is, of objective exteriorization) and individual social subjectivation (that is, of personal interiorization) of those same networks of social interactions that conform our everyday practices (family, educational, generational, community based, political, classist, religious, gender, racial, ethnic, etc).

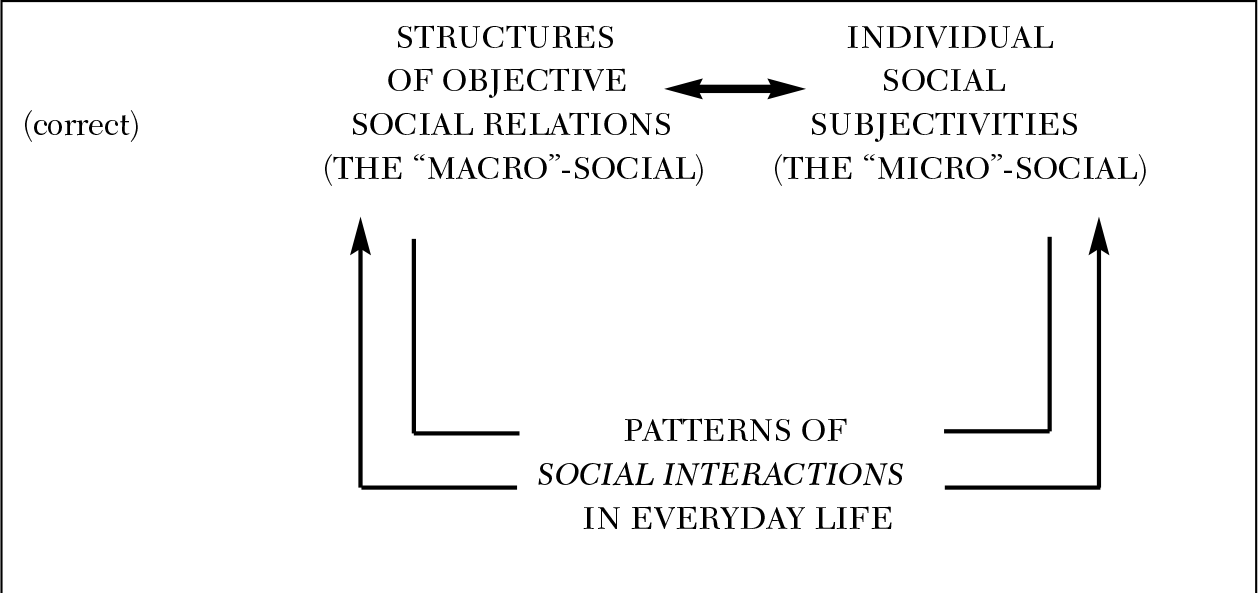

The biological metaphor stating that the “macro” accumulates as aggregates of the “micro” therefore seems not to work in society. Instead, what we social researchers name the “macro-social” (extended objective structures of social relations) and the “micro-social” (individual social subjectivities) are respectively produced and constituted, in parallel and simultaneous fashion, through the concomitant objectivation/subjectivation of the various patterns of networks of social interactions in everyday life.

That is, the macro-social and the micro-social are both constituted through the concomitant objectivation/subjectivation of the various regimes of collective practices characteristic of our day-to-day actions, patterns in which we find ourselves engaged from birth to our final day in their role as true dynamical social attractors. And it is in relation to these social dynamic attractors (social patterns) and through a variety of inter-pattern (inter-attractor) articulations of everyday life that our correlated behaviors emerge. In other words, it is as a function of these social attractors and inter-attractor links that social complexity emerges.

Once constituted, both the social objectivation (social relations thereby objectively structured) and social subjectivation (subjectivities constituted as social agents) of these regimes of everyday collective practices can impinge on the next “turn” or “circuit” of the pattern of social interaction in question, thereby contributing to the reproduction or modification of those everyday collective practices and to the further contextualization of what was produced by them in the first place.

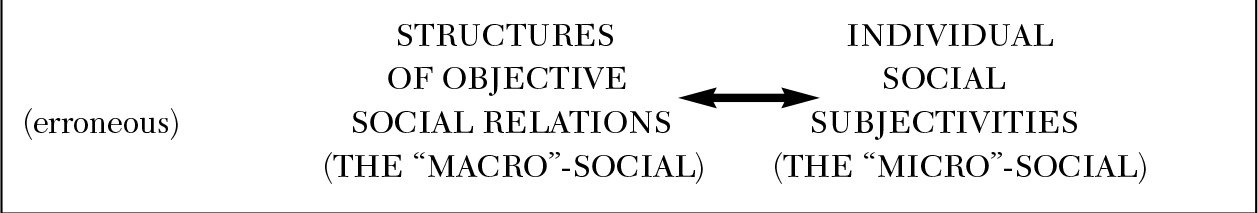

The generation of and articulation between the macro- and the microsocial, which is thus one of concomitance, mutual inclusion, reciprocal incidence, and co-generation, is therefore frequently and erroneously represented in the direct and immediate manner shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Erroneous representation of macro- and micro-social

Representing the relationship between the macro- and the microsocial in this manner imprisons us in the usual confrontational opposition between the two. We argue that, on the contrary, the macro- and the micro-social5 should be apprehended and represented in the indirect and mediated way shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Indirect representation of macro- and micro-social

As we emphasize in our above-mentioned work, patterns of social interactions in everyday life are always situated; that is, they always involve some whos, a where, a when, a what, a how, a what for, and a why (the seven so-called indexicals). Moreover, in addition to always presenting this indexical character, patterns of social interactions are always reflexive and open. That is, the results of each of their turns or cycles feed into the next one, and there is always in principle the possibility of another turn or cycle in their unfolding. All of this makes any pattern of everyday social interactions amenable to characterization in terms of a corresponding arsenal of qualitative social methodologies6 that can shed light on the specific content of those indexicals.

In order to characterize the determination directionality of inter-pattern articulations, we also emphasize the dynamical and processual nature of these interactions: their different “social reach or rank,” for example, the determining characteristic of classist patterns over family patterns of social interactions, the determining nature of both these patterns over the educational, cultural, religious, and other patterns of social interactions of everyday life, and so on.

It is also very important to keep in mind that each and every one of our patterns of social interactions (that is, of our regimes of characteristic collective practices of our everyday lives) unfolds within the already mentioned “situations of social interaction with co-presence.” Because these situations are the true and sui generis “social settings,” we can distinguish social bonds (for which the co-presence of those involved is unavoidable and for which the names of those involved are essential) from social relations (for which, although the co-presence of those involved is possible, it is nonetheless not unavoidable, and for which the names of those involved are not essential).

On the other hand, it is precisely within the limits of these situations of social interactions with co-presence that our “local” everyday practices of power, desire, knowledge, and discourse unavoidably unfold (that is, whether or not we are aware of them or like it). These situations are also where each of the practices articulates in circular fashion with the others. As has been stressed above, it is along with their objective exteriorization (objectivation) that structures of social relations are produced (educational, generational, community based, political, classist, religious, gender, racial, ethnic, etc.); and it is along with their subjective interiorization (subjectivation) throughout our lifetime that we constitute ourselves as social subjectivities (family, educational, generational, community based, political, classist, religious, gender, racial, ethnic, etc.). This last subjectivation process always proceeds, unavoidably, through three “ways of subjective registering”: consciously (reflexively), tacitly (pre-reflexively), and unconsciously (a-reflexively), all three of which contribute throughout our lifetime to the process whereby we become social agents.

OUR MULTIPLE-COLLECTIVE AND INDIVIDUAL-PERSONAL IDENTITIES

The foregoing helps us understand that each of us constituting any given society is simultaneously a “carrier” of multiple objective social relations (one for every pattern of social interactions of their everyday life), as a consequence of the fact that they are always objectively involved in those multiple objective social relations in a collective generic manner, an involvement in which their name is not essential.

This multidimensionality accounts for each individual's multiple social collective identities: father or daughter, teacher or student, young man or old woman, city man or village woman, political leader or rank-and-file partisan, worker or bourgeois, priest or parishioner, man or woman, black or white, indigenous or immigrant, and so on. Each of us is a social agent of multiple, individual, subjective dimensions, one for every pattern of social interaction of their everyday life, through they are always constituted in a specific personal manner, and for which individual subjectivity their name is essential. This subjectivity in turn accounts for their multiple individual personal identities: John Smith, or Juan Gonzalez, or Kim Ho Pak, or Hguyen Ti Sin, or Rabindranath Lore, as a particular father, teacher, old city man, political leader, worker, priest, white man, black man, and so on. Or Mary Stewart or Maria Sanchez, or Apsara Pindi, or Bukaya Manda, or Li Lien, as a specific daughter, student, village woman, youth, rank-and-file partisan, bourgeois, white, black, indigenous, parish member, and so on.

These characterizations also allow us to better understand what changes in the oft-cited processes of so-called social change.

WHAT CHANGES IN “SOCIAL CHANGE”?

We commonly express ourselves in terms of the need to “change the actual social structures” (evidently when they do not please us), or in terms of the need to “change people's mentality (ways of thinking),” that is, to change individual social subjectivities (obviously when those do not please us either). When we do so, we are dealing of course with the all-important topic of “social change.” However, in an explicit manner—or more frequently in an implicit one—we address (and even try to produce) those changes operating on those structures of social relations (and their institutions) and/or on those social subjectivities, directly and immediately (without mediation, that is). Nevertheless, given what has been argued earlier, we can assert that those purposes (well intentioned as they might be) never turn out to be directly realizable.

They do not prove themselves directly realizable for the simple reason that those objective social structures (and their institutions) and those individual social subjectivities, which do not please us, have been the result of (have been produced or generated by) specific regimes of characteristic collective practices of the everyday actions of real and specific men and women of that specific society. That is, they stem from specific patterns of social interactions in the everyday life of that specific society, and so it is these collective practices that are susceptible to being changed in a more or less immediate (that is, unmediated) fashion. Whether doing so is easy or difficult is a different matter.

In other words, the patterns of social interactions characteristic of everyday life in communities (human collectivities) in their role as sui generis dynamic social attractors are not the “what-ought-to-be-changed,” they are precisely the “what-changes-in-the-so-called-social-change.”

When they change—when those regimes of collective social practices characteristic of everyday life change—the objective social structures and the individual social subjectivities that were generated by the previous patterns cannot avoid changing, because the new patterns of social interactions (those new types of characteristic and recurrent collective practices), as they renew the dynamic landscape of social attractors in that specific society, produce and generate different objective social structures and their institutions, and different individual social subjectivities (people with another mentality and another “way of thinking”).

SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS AND ORGANIZATIONS AS REGIMES OF CONCOMITANT PERMISSIONS AND PROHIBITIONS

In our work on patterns of social interactions in everyday life, we argue extensively that one or another social “institution” represents no more—but no less—than a social “space” (that of the state, the law, the family, education, religious life, etc.) in which a parallel and simultaneous regime of social permissions (the “what-is-socially-allowed”) and social prohibitions (the “what-is-socially-forbidden”) has been established (“has been instituted,” we are accustomed to saying).

Social “spaces”—and social permissions and prohibitions—are associated with one or another characteristic collective social practice (political, juridical, educational, family, and religious day-to-day practices, etc.). Social institutions, therefore, are no more—but no less—than the institutionalization of one or another pattern of social interaction of everyday life, regimes of concomitant permissions (socially allowed practices) and prohibitions (socially prohibited practices) that are established in one or the other of those social “spaces of practices.”

Thus, depending on the specificity of the pertinent type of practice institutionalized, that regime of parallel social permissions and prohibitions can be:

- Tacit (for example, that of the family as a social institution), when it is not necessary to enact those social permissions and prohibitions explicitly in order to have the “what-is-allowed” and “what-is-prohibited” by them observed by the vast majority of those concerned.

- Explicit (for example, that of the law as a social institution), when it is necessary to have those social permissions and prohibitions explicitly known in order to have the “what-is-allowed” and “what-is-prohibited” by them observed by the vast majority of those concerned.

- Organized (for example, that of the school we attend, the enterprise we work in), when besides making them explicit, those social permissions and prohibitions need to be properly regulated, overseen, and controlled on a more continuous basis in order to have the “what-is-allowed” and “what-is-prohibited” by them observed by the vast majority of those concerned. (When that necessity arises, the concerned social institutions create the organizations that they deem suited for that more day-to-day regulation, overview, and control.)7

Thus, an organization (school, church, political party, enterprise, club, etc.) is an explicit and organized social institution, an explicit and organized regime of concomitant social permissions and prohibitions concerning a specific “space” of characteristic collective social practices. So when we want to change an organization, what we ought to change first is not its structure of objective social relations, or the minds of those engaged in it, but its characteristic collective social practices. The new, alternative pattern of collective organizational social interactions achieved will generate a new structure of organizational objective relations and a new mentality in those engaged in it.

Neither an a priori structural “change” nor bringing someone with another frame of mind into a key post changes the organization as such. Such changes can only be instrumental retrospectively (and by previously modifying what is currently allowed and what is currently prohibited in the practices of those involved in the organization) in achieving the proper change in the collective social practices characteristic of the organization (its characteristic pattern of organizational social interactions). And the best way to achieve that new pattern of social organizational collective practices—as the “complexity approach” shows—is not by top-down, voluntaristic, I-order-and-you-obey, global-pattern-imposing, hierarchical-minded means, but, on the contrary, through bottom-up, emergent, self-organized, local-pattern-recognizing, network-minded means.

As we try to show in our work, for this to be achieved proper account must always be given to the above-mentioned four social-complexity-generating specific social affordances (power inducing and/or power induced; desire inducing and/or desire induced; knowledge inducing and/or knowledge induced; discourse inducing and/or discourse induced) that always conform and characterize one or other of the different regimes of concomitant allowances and prohibitions that inherently constitute the organization concerned as such. It is only through the adequate modification of these organizational social asymmetries that unfold in terms of power (ambitions, interests, goals, etc.), desire (compulsions, needs, demands, etc.), knowledge (intuitions, tacit wisdom, formalized knowledge, etc.) and/or discourse (linguistic abilities, everyday speech, argumentative enunciations, etc.) that convenient bottom-up, emergent, self-organized, network-like, local-pattern-recognizing, socio-organizational correlated interactions can be elicited. They cannot be dictated, imposed, or declared, but instead can only be facilitated, promoted, and encouraged. This is what good contemporary organizational management and direction are all about.

DIALECTICS OF ARTICULATION BETWEEN THE “PERSONAL” AND THE “SOCIAL” IN SOCIAL CHANGE

That the “what-needs-to-be-changed” and the “what-does-change” in social change are in fact the above-mentioned features of patterns of social interactions or regimes of characteristic collective social practices of everyday life does not eliminate, but on the contrary presupposes, the important question of the need for a dialectic between the “individual” and the “collective,” or the “personal” and the “social,” or, even better phrased, between the “individually social” and the “collectively social” in social change.

In this connection, in our work we have argued that in principle, for a new pattern to be realizable and for that new pattern to become eventually a new reality, it suffices that either a single “who” or a small number of those involved in any given pattern of social interactions initiates efforts (which at first frequently have all the odds against them) to establish a new (because of different and alternative to the current one) pattern of characteristic everyday practices (family, educational, generational, community based, political, classist, religious, gender, racial, ethnic, etc.) for that new pattern to be in principle realizable, to turn eventually into a social reality. Whether the change is probable is an entirely different question, one that depends strongly on the specifics of the pattern of social interactions attempting to be modified.

In light of this last comment, it is pertinent to emphasize that in the context we have been dealing with (the individual/personal-collective/social involved in processes of social change), the fact that the dialectics of social articulation is heavily dependent on the specifics of the social pattern involved means that the “social price” to pay (the social risk to face) by those “whos” intent on social change can be extremely varied. As ancient, medieval, modern, and contemporary history shows, efforts to change qualitatively a specific society's current pattern of everyday political or religious social interaction can come at a high price, including the loss of the agent's life. Thus it follows that it is only when and if the new and alternative pattern of social interactions has successfully become typical of everyday life that the individual who initiated that change, and those who were the first to go along with them in that effort, can be identified—and only a posteriori—as the religious, political, classist, educational leader, and avant garde respectively (depending on the pattern of social interactions that has been qualitatively changed).

This sociological understanding leads to a definition of leadership and vanguardist action that, unlike the usual definitions, is not a priori, since it depends on the prior establishment and verification of some specific social results of the process of social change involved.

NOTES

- The following can be conventionally distinguished: “horizontal” patterns of social interactions (family, educational, classist, etc.) that refer back to factors of social origin, and “vertical” patterns of social interactions (gender, race, ethnic, etc.) that refer back to so-called invariants of origin of an ethno-biological nature. The latter “transversally” cross-sections the former and thus one can distinguish in the same classist pattern of a specific society subpatterns relating to color; or, for example, in the same family pattern of that society, masculine and feminine subpatterns; or in the same educational pattern different subpatterns for the autochthonous ethnic population and for the immigrant population. In other words, a pattern of social interactions in the same society is not “lived,” is not “practiced” in the same manner by people of different colors; or by a man and a woman; or by someone belonging to an autochthonous ethnic tribe, an immigrant, etc.

- “Context-sensitive” means that such networks of social interactions of everyday life carry the imprint of “what-has-happened-to-them” (of their history), as well as of “what-is-happening-to-them”(of their specific context of interaction). See Juarrero, A. (1999) Dynamics in Action: Intentional Behavior as a Complex System, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Michel Foucault has convincingly elaborated on these social “domains,” especially with respect to what he called social “positivities,” that is, pre-reflexive regimes of social practices that conform to much of what we are interested in, need, tacitly know, and currently enunciate in our everyday life.

- “Local” social practices in the sense that they take place within so-called situations of social interactions with co-presence of those involved. Such “situations of social interactions with co-presence” of everyday life provide the social scenarios (settings)—always situated and specific—where each time one or the other of our patterns of social interactions unfolds in everyday life.

- We should note by the way that such representation is “trapped” inside the dichotomous, bivalent (Aristotelian) logic that we usually employ, without such utilization being accompanied by a reflexive attitude about its limits and limitations; as if it were the only logic that we could employ or as if this dichotomous form were the only adequate one to a dialectical thinking.

- Participating observations; open-ended interviews; in-depth interviews; life histories; discussion groups; real-group dynamics; case studies; field studies; institutional studies and/or interventions; action-oriented researches; participating action-oriented researches; a combination (triangulation) of two or more of these qualitative approaches.

- Needless to say, all organizations (organized institutions) are inherently explicit institutions, but the inverse is not always the case; not all explicit institutions are organizations, although many of them do have organization. In this latter case, we need additionally to distinguish the organized institutional space (the organization, properly speaking) that has been necessary for the explicit institution to function from the often co-existing explicit (but not organized) wider social “space” occupied by that institutional regime. The juridical, educational, and religious realms, as social “spaces,” are examples of the co-existence of both, explicit (but not organized) juridical, educational, and religious institutions, and juridical, educational, and religious organizations.