Complexity, complicatedness and complexity:

A new science behind organizational intervention?

If Price

Sheffield Hallam University, ENG

Abstract

This paper explores the origin of costly complexity/complicatedness from a stance in evolutionary complexity. It argues that the tendency to the former is a property of the evolution in the latter. The creation of space, physical and virtual for adaptation may be a managerial solution - one amenable to various interventions which draw upon complexity as a metaphor.

Introduction: Three senses of complexity

One of my personal favorite definitions of ‘life’, and complexity, is that offered by Richard Dawkins, (1988)

“[Life is] ... a property of improbable complexity possessed by an entity that works to keep itself out of equilibrium with its environment.”

To exapt Dawkins’s most graphic example: a dead parrot thrown into the air obeys the laws of physics, describes a perfect parabola, and then falls back to earth. A live one disappears over the county boundary; its component parts working together to maintain their collective entity against the force of gravity. The definition can also be generalized. One scientific measure of the complexity in any system is the degree to which it maintains a thermodynamic disequilibrium with its environment; defies in effect the second law of thermodynamics. Living systems, whether biological or cultural, not only display this form of complexity, they also maintain it over time.

The scientific measure of complexity ignores of course other senses in which the word has entered the discourse of social and managerial researchers and practitioners; senses explored in this volume and triggered in no small part by the scientific studies of complex systems (Waldrop, 1992). Predating this current usage, and perhaps for practitioners the common sense understanding of the word, is as a description of the shear cost and burden of organizational bureaucracy. Working in a multinational enterprise I encountered the term ‘cost of complexity’ (and organizational concern about it) when my then boss returned from a group management conference in November 1988. The firm was one of many making a similar discovery at the same sort of time. ‘Cost of complexity’ provides a metaphor for the forms of business concern that launched, in the 1990s, many movements for organizational change and the growth of outsourcing. In 1988, judging at least from titles on the Proquest database, the term ‘outsourcing’ was restricted to manufacturing industries procuring rather than making components. A decade later business theorists were able to note that “the practice of outsourcing has grown rapidly in the past decade” (Coombs & Bataglia, 1998) and argue for its use to be restricted to “knowledge services rather than materials or component procurement.”

Such complexity, and the consequent rise of outsourcing, challenges the theoretical justification of the firm being able to transact internal business more cheaply than the market (Coase, 1937/1991). The administrative and managerial costs of the organization and the opportunity costs of organizational inertia at some point, outweigh any benefits of transaction cost control. However such complexity is not restricted to single organizations. Transactions between ‘suppliers’ and ‘purchasers’ incur costs of procurement in, for example, the writing of tender specifications, the tendering process, the tender evaluation, the negotiation of a contract, the legal and professional specification of contracts and the resolution of subsequent disputes. In theory at least, such processes ensure the purchaser of receipt of the best value for money, and the be st governance over the expenditure of stakeholder investment. Yet a powerful argument exists for the benefits to all concerned of the reduction of such costs by what is generally termed ‘partnership sourcing’ (e.g., Kay, 1993; Egan, 1999).

In a third sense, complexity has become an umbrella under which advocates of whole system approaches to issues of organizational change and development can gather. As a metaphor of holism it has become a powerful counter to mechanistic views of organizations and organizational change. Proponents of a retreat from Newtonian theories of organization or Taylorist approaches to management find common ground in this form of ‘complexity’.

My aim in this paper is to explore an underpinning theoretical stance that can perhaps aid an appreciation of all three senses of ‘complexity’. The endeavor requires that the senses be distinguished. The first (in the order used above) sense - the understanding ofnon-equilibrium systems or the science of ‘complexity’ has made great strides in the last 15 or so years driven notably by the work of the Santa Fe Institute and the numerous books which have exposed that work to a wider lay audience (Waldrop, 1992; Lewin, 1992; Kauffman, 1993, 1995; Gell-Mann, 1994; Holland, 1995). There is now a science of Complex Adaptive Systems, one I will aim to distinguish as ‘hard-c' complexity1. The third sense, many of whose advocates have drawn inspiration from complexity I will label as the more general complexity (without the emphasis). The intermediate sense (again only in terms of the order above) might be termed organizational non-simplicity. However the more common description, among those who make the distinction in the general field of ‘complexity'2, seems to be ‘complicatedness'3 and I will use that term here. I will argue complicatedness as an emergent property of complexity in organizations, one amenable to the tools and approaches of complexity especially when understood as such.

Fad or fashion? ‘Complexity' as self-replicating discourse.

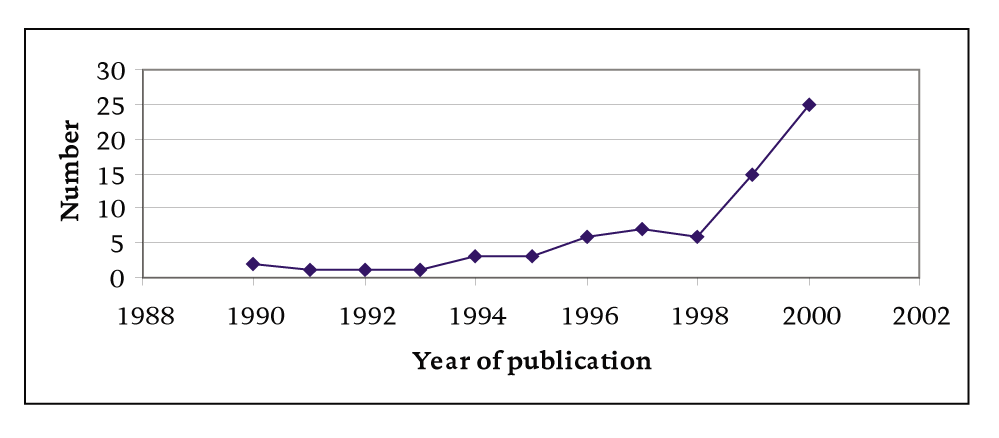

Pascale, (1990) drew attention to the propensity of management (at least in the West) to seek the latest fad; a trend he illustrated by reference to an overall proliferation of such fads and a common ‘S-curve' dynamic to each. Subsequently, with the less pejorative label of business fashions (Abrahamson, 1996), the study of fads/fashions has become a field of interest in its own right. Tracking use of a particular term in business orientated literature provides a measure of its penetration in the general arena of managerial discourse. Quality circles rose to prominence and declined to insignificance (Abrahamson, 1996). Currently references to ‘knowledge management' are still rising exponentially, apparently to the detriment of ‘learning organization' (Scarborough & Swan, 1999). ‘Benchmarking' (Price, 2000) and ‘Facilities Management' (Lord, et al., 2002; Price, 2002) both enjoyed periods of exponential growth in the early 1990s but their expansion has slowed. If books for the general reader4 in the Amazon.com database with ‘complexity' in the title (Figure 1) can be taken as a guide, ‘complexity' is following the same trend. There is a common dynamic in each case. As a particular discourse spreads it generates its own momentum via positive feedback, and sustains a loose organization of researchers pursuing grants, publishers pursuing titles, and consultants pursuing market differentiation. Some (e.g., quality circles) emerge and fade completely. More successful examples such as Total Quality Management (TQM), Business Process Re-Engineering (BPR), Knowledge Management (KM) or indeed Facilities Management (FM)5 sustain institutes, journals, research centres and other forms of organization which serve to further propagate the ‘fad/fashion' concerned. At times two or more may compete for space in the same cultural niche. The late 1980s and early 1990s saw numerous variations on Business Process change emerge of which only ‘reengineering' survived to ca. 1995 (Price & Shaw, 1996).

Figure 1 Complexity titles by year of publication. Source: Amazon.com

The various forms of organization which help propagate a particular management fashion, show complexity. They maintain a form of order, a particular departure from thermodynamic equilibrium that would not exist without a particular discourse, in this case ‘complexity'. That order is emergent. The coalition of fashion propagating ‘organizations' is self-organizing. As reference to other contributions in the volume testifies, the process does not demand a single accepted and precise definition of ‘complexity'. The same is true of other successful fads. As ‘Business Process Reengineering', ‘Learning Organization' (Price & Shaw, 1996), ‘Benchmarking' (Price, 2000a) or Facilities Management (Price, 2002) spread each gained several meanings.

Complexity, as science, seems able to explain how such emergent order, self-organization, is a property of networks of interconnected agents each operating to consistent but simple rules. While some pioneers in the field, notably Kauffman (1993, 1995) have stressed the density of interconnection others have stressed the agents following the same rules (Holland, 1995). Gell-Mann (1994) takes the proposition one stage further arguing the need for rules encoded in the ‘schemata' in any Complex Adaptive System. If first, these propositions are correct, and second the ‘fad' based examples above are accepted as emergent self-organization, then it should be possible to identify the schemata at work. In part, they are bound up with the unwritten rules (Scott-Morgan, 1994) of academic research and consulting. Disseminating a particular fashion helps the agents who participate, whether they are driven by a desire to earn reputation and grants/fees or pleasure in the act of scholarship. However, each individual case, each self-organizing system propagating a particular fashion, or exploring a particular domain of academic enquiry, also requires a unique schema; the particular ‘fad' or ‘domain' concerned. The concepts encoded in a particular discourse give rise to a particular self-organizing system that in turn perpetuates and disseminates the discourse. To the degree that, that system represents order, or a nascent form of organization, it is enabled by the same discourse.

The process, emergent self-organization around a replicating discourse, can be argued as a relatively simple, and perhaps even simplistic, case of a more general phenomenon. Different fields and subsets of scientific scholarship can be considered as forms of organization enabled by, and dedicated to the maintaining of, particular paradigms (Hull, 1990). More generally organizations can be held to depend on the organization ‘rules and procedures' (Hannan & Freeman, 1977) or ‘institutions' (Powell & DiMaggio, 1991). Such rules are largely unwritten (Scott-Morgan, 1994) and may be called into existence through organizational discourse; discourse frequently shaped by the metaphors which give it meaning (Morgan, 1996). Paradigms, for Hull, (1990) and most scientists, are selected according to their ability to provide better, truer, explanations of the world but his argument, substantiated by detailed evidence, is that the institutions organized around a particular paradigm resist the intrusion of a replacement. Postmodern organizational scholars are more likely to take a stance against a single objective reality in favor of one called into existence by particular metaphors or discourses, but might find common ground in recognizing the organizational resistance to the introduction of newer ideologies. I will argue below for this common ground. Complexity, as more paradigm than metaphor, can help those who use complexity as metaphor in designing organizational interventions. For the moment however the argument is that ‘complexity', simply as an item of discourse, has enabled the emergence of a network of organizations whose existence automatically leads towards the term's further dissemination. Why then the diversity of meaning that adds a measure of complicatedness to discussions of ‘complexity' in its many guises? Why the same phenomenon in the other examples provided above?

Cui bono: Why the diversity of meaning?

Who benefits from the diversity of meaning inherent in ‘complexity', or similar ‘fads'? Hardly the users except perhaps insofar as debate over meaning becomes an area of scholarship in its own right. Certainly not students or business clients seeking to evaluate the utility, to them, of the term. Perhaps (c.f. Dennett, 1991, 1995) the question is framed by a limiting assumption that a ‘who', an individual or group of individuals, benefit. Dennett's argument would be that we should consider the question from the benefit of the term ‘complexity' itself as a piece of discourse. If diversity of meaning aids the spread of a particular term then the term itself can be considered to have benefited.

In making the case Dennett is of course drawing on the Darwinian evolutionary paradigm and especially on the currently dominant neo-Darwinian version that treats evolution as a selection process between replicators. Dawkins's (1976, 1988) metaphor of The Selfish Gene6 has become the popular expression7. The essence of the argument is that genomes carry the schemata for complex biologic order. Their inherent property of replication, via the phenotypes they encode for, underpins the emergence and maintenance of biological complexity. More specifically however, Dennett is drawing on Dawkins's suggestion of a second, cultural replicator, the meme; a belief, fashion or idea that replicates, not chemically, but in a broad sense through imitation. It is to Dennett, (1995) that we owe the metaphor of the lawyers' question asking ‘who benefits' of a ‘selfish' replicator?

The case for memes has been argued elsewhere; as underpinning a theory of socially contagious behavior in individuals (Marsden, 1998; Blackmore, 1999) or as the foundation of a more general theory of individual consciousness (Dennett, 1991; Gabora, 1997). A wider view would see memes, or complexes of coexisting memes, as encoding a schemata for cultural organization8 (Hull, 1990; Lloyd, 1990: Price, 1995, Price & Kennie, 1997; Price & Shaw, 1998, Weaver 1998, Balkin, 1999; Williams, 2000; Weeks & Galunic, 2003). With differences of emphasis, these authors all argue for organizational ‘rules' as a product of a self replicating system of ideas and dialogue; in essence a Foucauldian discourse.

The examples of managerial fads and fashions provide a simple example of the process at work: organization is an emergent property of the replication of a discourse. Complexity arises from and is enabled by that replication. However if we take Dennett's (and others') stance we look at the benefits not from the viewpoint of the agents in the system but from that of the replicator - if we consider the discourse ‘complexity' as a ‘selfish meme', replicating by leaping from mind to mind - the lack of clarity as to meaning is a positive benefit. The meme is replicated every time someone joins a discussion as to its meaning and gains more space in the ecology of human conversation the more different meanings it conveys9. “We are less what we speak but more what speaks us” (Dennett, 1991 citing Lodge's 1988 portrayal of postmodernism in critical theory). The example serves as a generic explanation for the emergence of complicatedness.

Organizations as complex adaptive (?) systems

Complexity has provided the concept of Complex Adaptive Systems (CAS); systems that display not only the emergence of self-organizing order but also the maintenance of that order over time. In general terms the biotic and the abiotic domains offer two isomorphic meta-groups of CAS. The term adaptive is however unfortunate in that both domains spend long periods veering towards self-maintenance or autopoiesis (Winograd & Flores, 1987; Mingers, 1994) rather than adaptation. In simple terms a literal comparison of the two systems (summarizing Price, 1999) is as follows:

- Nonlinear, or partially deterministic, self-organization - a property inherent in many natural systems - arises from some critical density of interconnectivity, and the presence in the system of schemata, rules governing the interaction of the systems agents. It is revealed by a power law relationship between magnitude and frequency.

- Within the set of self-organizing systems is a subset which also show the property of self-maintenance (broadly autopoiesis), hence, for example, over time the magnitude of extinction events in the geological record, departs from a power law relationship. Kauffman's (1993) interpretation of Raup's (1992) extinction data fits the post uniformitarian view of the stratigraphic record (Ager, 1973), and the punctuationist, or none steady-rate, interpretation of speciation events over geological time. A similar punctuated dynamic may be observed in the history, or evolution, of social systems at many scales, (e.g., Gersick, 1991; Tylecote, 1993; Rothschild, 1992; Hodgson, 1993; Price & Evans, 1993).

- Within the biological domain the schemata are encoded as genes, complicated systems of information with the ability to specify structures that will, in turn, create copies of themselves. Granting the selfish gene as “a metaphor for a system of interconnected genes of almost indescribable complexity” (Dawkins, 1976), granting their operation as part of a complex feedback system involving their immediate, and wider environment, and granting that selection for reproductive continuity operates on vehicles (individual organisms) rather than directly on genes or genomes, the assertion made here is that no satisfactory alternative has been found for Darwin's Dangerous Idea (see Dennett, 1995) as the origin of order. Within the abiotic domain schemata are encoded in complicated systems of metaphors, paradigms, mindsets, belief systems, artefacts, and institutional traditions. Conceptualizing this mix as memes with the inherent tendency to self replication, provides either a literal explanation from which to understand organization or, if one is imbued with a different tradition, a rich new metaphor from which to examine organizational behavior. Complexity theory enriches rather than replaces the basic tenet of natural selection as the source of biological complexity. It will help us appreciate ‘the origin of order' but is by, and of itself no escape from Darwinism or the ‘Selfish Gene'. Kauffman, (1995) makes the same point with his plea for “a proper marriage of self-organization and selection” to tell us “who and how we are in the non-equilibrium world we mutually create and transform.”

- Evolving biological systems have an inherent tendency to seek an evolutionary stable strategy (ESS) one which is stable until perturbed by an evolutionary crisis. Cui Bono again! The system of selfish replicators benefits from stasis. Price and Kennie (1997) have suggested four classes of such events and explored potential analogues on the strategic rather than the stratigraphic timescale.

By thus granting the schemata in either system the status of replicators one arrives at an explanation of the lack of adaptation in either domain. One also arrives at a theory of organization capable of embracing both evolutionary economics (Rothschild, 1992; Hodgson, 1993; Tylecote, 1993) with its emphasis on ‘rules' and technologies as cultural replicators, and Hull's (1990) allocation of paradigms to the same role and concepts of social construction of organizations through discourse and institutional tradition. The firm is an intra-organizational ecology of memes (Weeks & Galunic, 2003) participating in a wider memetic ecosystem.

One valid objection to the proposition of memes in this context is that it adds nothing to these older evolutionary epistemologies. Alternatively it grounds each of them in a replicator based view of the emergence of order and provides some unifying framework into which each can fit. As a species Homo Sapiens is distinguished by cranial capacity and linguistic capability. Our verbal capabilities and large brains enable us to create and express, through conversation, sense-making: descriptions of the world we inhabit. Metaphor, or even catalytic indexicals (Lissack, 2003), may be a vital component of the process (Grant & Oswick, 1996) and we should perhaps conceive of metaphors as memes. From sensemaking coevolved the capability of creating technological artifacts with which to modify our world, rules for collective behavior so as to make better use of the potential of technology and belief systems that both enable technological evolution and legitimize collective rules or norms. We have seen, over perhaps 5,000,000 years of artefact making, 50,000 years of art making, 8,000 odd years of agriculture and 200 years of the exploitation of fossil fuels, the explosive coevolution of beliefs, language and technological artifacts; the exponential growth of cultural complexity10 and indeed complicatedness.

Complicatedness

Can the memetic stance on that complexity offer an explanation for the emergence of complicatedness? Can it explain the effectiveness of interventions based on complexity? The answer in both cases seems to be yes.

Consider for a moment the biotic domain and the complex of interacting selfish genes. The amount of complexity - negative entropy or biomass - devoted to their replication rather than that of some rival complex determines their ‘success'. Abiotic complexity produces not biomass but the combination of knowledge and artifacts that we term ‘wealth'11 or ‘value-added'. Success, in selfish replicator terms, may be considered as the amount of the value generated in a given economic system diverted to the replication of a particular meme. Dawkins, (1988) has used the example of the legal profession as evidence of the emergence of spontaneous collaboration. Two or more members of that profession, engaged by the parties to a particular dispute, tacitly collaborate in maintaining the dispute. This is not to impugn in any way the professional integrity of either. By following the general mores and codes of a given legal system, their particular legal institutions (sensu Powell & DiMaggio, 1991), both divert to that system and its replication a share of the value in dispute. This is not to say that the system serves no purpose. Economists will argue the existence of a legal framework within which trade can take place as an essential component of an advanced economic infrastructure (Casson, 1993). It is part of the memetic pattern that enables a particular form of wealth creating society to function - Balkin's (1999) ‘prevailing ideology' - but also seeks to divert that wealth towards its own replication. The complicatedness of the legal dispute benefits the legal meme, or legal memes, (and its their carriers), but becomes value subtracting rather than value creating12.

Lest this seem like an attack on lawyers, it is offered as no more than a simple example of inter-organizational complicatedness. Subsets of other professional memes contribute to value generation in, but also value diversion from other forms of organization. A large organization, as Weeks and Galunic (2003) emphasize, encompasses many memetic subsets. Teams and departments of strategic planners are for example still a common feature of corporate management. The value they add is debatable. Mintzberg, (1994) has argued, perhaps for some rhetorical effect, that “the only organization to have benefited from strategic planning is the profession of strategic planning.” Whittington (1993) draws attention to the tendency for the size of corporations to rise, not to the point at which benefits of scale maximize the economic return to investors, but to the largest size management can create without investors becoming dissatisfied with their return. The complicatedness of additional growth benefits a particular set of managerial memes, but diverts resources to their replication rather than to the process of value creation. The tendering process referred to earlier justifies the activities of procurement and other professionals engaged in the construction and interpretation of contracts and the resolution of the resulting disputes. Professional memes of various kinds are replicated as those who carry them create a perceived demand for their services. The Egan Report, and the subsequent much publicized efforts by the UK construction industry to change many of its traditional working practices, drew much inspiration from the CRINE13 initiative in the UK's Offshore Oil industry. That initiative had its origins in the realization that the complicatedness which had emerged in the industry in its boom years (ca. 1975-1990) had produced a cost structure in which a new generation of smaller fields would be impossible to develop. The beneficiaries were the legion of different professionals who contributed to the emergence of such complicatedness14 and the memes of those particular professions.

Hence another proposition to add to those made above:

- Complicatedness, the value subtracting managerial /professional/administrative complexity found in organizations and supply chains, is an inherent property of emergent memetic systems.

This is not to say that it will inevitably persist. New, less complicated, organizational forms produce new market offerings, new space is created for new ‘fads' which offer the possible solution to the management of complicatedness and sometimes reactions in the wider political or economic environment impose limits to growth. Over-complicated organizations often go extinct. Their successors emerge with the same danger of unadaptibility.

Complexity

If the thesis presented above is valid, or if the metaphoric perspective is appreciated, complicatedness is an offshoot of complexity. Complicatedness, in turn, generates much of the need for the third sense of ‘complexity': the forms of organizational intervention coming to be considered as complex. The shift from the industrial to the post-industrial age represents a major punctuation of the economic equilibrium of to which many organizations have adapted15. Organizational complicatedness hampers efforts to change and approaches to change rooted in mechanistic and reductionist paradigms of organization are increasingly suspect. Newer, whole systems, interventions are by no means guaranteed. Some are inappropriately designed and others fail to sufficiently interrupt the inherently autopoietic patterns in organizations to which they are applied (Price & Shaw, 1998; Batchelor, et al., 1998).

All complexity based approaches share the property of trying in some way to expose or amend limiting aspects of an organizations unwritten rules, stories, behavioral norms, mental models or language. Designing processes and environments (physical or virtual) where different forms of conversation can occur becomes the job of the complexity consultant16. It is a form of memetic engineering, or memetic cultivation for those for whom the engineering metaphor signals danger. Hence another proposition

- Complexity based management of change and innovation is a process of creating physical and mental space in which different conversations can occur and out of which new possibilities are created.

There are analogies with genetic modification, but they are imprecise. At the current state of understanding GM technology seems concerned to splice particular genes from one species into another the better to engender some desired (whether desirable or not) property. I am not aware of people designing new genes from scratch. The same is not true of memes. Some may be transposed from one context to another, others may be genuinely new. If a memetic stance, or metaphor, enables groups to have more creative conversations and to explore limiting perceptual models more easily then it serves a useful purpose. I argue that it can, and complexity then becomes an antidote for complicatedness, itself a by product of complexity.

Science or not?

I have of course ignored in the above, critics of both the neo-Darwinism from which memetics springs, and critics of memetics itself. There are biologists who have sought alternative explanations for the origin of biological complexity; driven perhaps by concern at the implications others have drawn from ‘survival of the fittest' as a metaphor for human society. Stephen Jay Gould is most often cited; despite numerous essays in which he has made clear his admiration of Darwin and his refusal to challenge the basic tenet of natural selection. Readers of Gould and Dawkins will be familiar with the debates. Gould's arguments condense to three:

- Evolution, at least in the sense of speciation, is not gradual. Episodes of, geologically, short punctuated equilibrium intersperse with long periods of stability.

- Selection acts not on genes but on organisms.

- Selection has no place in theories of cultural or human social behavior.

On the first the weight of geological evidence is very definitely on Gould's side. Ager (1973) presents a readable account while Kauffman, (1993), also much quoted as disproving Darwinism, concedes that the pattern of geological extinction with time shows a tendency to depart from pure ‘edge-of-chaos' self-organization. Biological observation of speciation being easier in peripheral isolates than in large populations is consistent with the point that a dominant system of ‘selfish genes' will resist changes if they can (Price, 1995; Price & Shaw, 1998: ch. 4). On the second Gould seems on less sure ground and majority opinion would now align behind Hull's (op cit.) distinction of replicators, the genes themselves, and vehicles, the genetically encoded constructs through which selection and replication is accomplished.

The third point is more contentious. Undoubtedly ‘social Darwinism' has earned its bad name as an excuse for eugenics and ethnic cleansing to name but two. On the other hand, a human tendency to see ourselves as superior to the rest of the biosphere, and to treat the environment as solely an amenity for our exploitation, could have a similar downside. A failure to respect our place in the biosphere is arguably at the root of various looming environmental threats. It seems, and this of course is a personal perspective, that appreciation of society as part of, rather than separate to, an evolved biosphere is a stance of hope rather than threat. Many may not agree, as witnessed by reactions to the current evolutionary psychologists who argue for much, perhaps all, behavior having a genetic source. Paradoxically for many (Casti, 1990), the concept of the self-replicating meme as a unit of cultural selection can be considered one of the major counter arguments to genetic determinism which nonetheless remains within the search for a scientific explanation of cultural complexity. Memetics is a counter to the full genetic determinism of evolutionary psychology.

There is then the view (e.g., Capra, 1996; Goodwin, 1994) that complexity in some way displaces Darwinism. Species are the result of some form of emergence and cannot be reduced to their genes. Dawkins, whose work I have obviously drawn heavily upon, is labelled one of the arch reductionists despite his references to the ‘complexity' of the functioning of genetic systems. For me at least, such explanations miss the point. There is an elegant and minimal simplicity in seeing information, encoded in auto-replicating structures, as the underlying schemata from which complex systems self-construct. The autocatalytic properties of complex networks (Kauffman, 1993, 1995) and the properties of agent based systems render it easier to appreciate the workings of genetic systems. In and of themselves they cannot make a case for life without genes.

Whether memetics, or a memetic stance on complexity can be falsified or not, whether in that sense it meets the Popperian criterion of a science, remains an open question. It offers however a minimalist heuristic (Marsden, 1998) from which to develop an evolutionary perspective on social phenomena. If perhaps we take Lloyd's (1990) view of corporations, and other large organizations with a tendency towards economic parasitism (Rothschild, 1992) as ‘an alien species' we have a scientific basis for treating them as intentional systems (Weaver, 1998) and an insistence on greater organizational accountability. If the memetic stance is valid we are, like it or not, caught in the rapids of non-biotic evolution. The selfish meme perspective may grant greater ability to understand, “who and how we are in the non-equilibrium world we mutually create and transform” (Kauffman, 1995). The metaphorical marriage of reductionism, replicators and complex wholes is one of hope more than despair.

NOTES

References

Ager, D. V. (1973). The nature of the stratigraphical record, Macmillan Press.

Abrahamson, E. (1996). “Management fashion,” Academy ofManagementReview, 21(1): 254-285.

Balkin, J. M. (1999). Cultural software: A theory of ideology, New Haven, Yale University Press

Batchelor, J., Price, I. and Shaw R. (1998). “Organizational transformation: The dynamics of learning and evolution of complex adaptive systems,” in Proceedings of the Organizations As Complex Evolving Systems Conference, Warwick, December, pp. 280-292

Blackmore, C. (1999). The meme machine, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Pres.

Capra, F. (1996). The web of life: A new synthesis of mind and matter, London, UK: Harper-Collins.

Casson, M. (1993). “Cultural determinants of economic performance,” Journal of Comparative Economics, 17: 418-442.

Casti, J. L. (1990). Paradigms lost: Images of man in the mirror of science, Scribners.

Cilliers, P (1998). Complexity and postmodernism, London, UK: Routledge.

Coase, R. (1937). “The nature of the firm,” in O. Williamson and S. Winter (eds.), The nature of the firm: Origins, evolution and development, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, pp. 18-33

Coombs, R. and Bataglia, P. (1998). “Outsourcing of business services and the boundaries of the firm,” Manchester CRIC Working Paper No 5. http://nt2.ec.man.ac.uk/ cric/Pdfs/ WP5.pdf.

Dawkins, R. (1976). The Selfish Gene, 2nd edition 1989, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Dawkins, R. (1988). The blind watchmaker: Why the evidence of evolution reveals a universe without design, London, UK: Longmans.

Dennett, D. C. (1991). Consciousness explained, Little Brown.

Dennett, D. C. (1995). Darwin’s dangerous idea: Evolution and the meanings of life, Penguin Press.

Egan, J. (1999). Rethinking construction, Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, http://www.construction.detr.gov.uk/cis/rethink/index.htm.

Gabora, L. (1997). “The origin and evolution of culture and creativity,” Journal of Memetics - Evolutionary Models of Information Transmission, 1, http://www.cpm.mmu.ac.uk/jom-emit/vol1/gabora_l.html.

Gell-Mann, M. (1994). The quark and the jaguar: Adventures in the simple and the complex, New York, NY: W. H. Freeman.

Gersick, C. J. (1991). “Punctuated equilibria as a model for organizational change,” Academy ofManagement Review, 16(1): 10-23.

Goodwin, B. (1994). How the leopard lost its spots: The evolution of complexity, New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Grant, D. and Oswick, C. (1996). Metaphor and organizations, London, UK: Sage.

Hannan, M. T. and Freeman, J. (1977). “The population ecology of organizations,” American Journal of Sociology, 82(5): 929-964.

Haynes, B. and Price, I (2004). “Quantifying the complex adaptive workplace,” Facilities, 22(1/2): 8-18.

Hodgson, G. M. (1993). Economics and evolution: Bringing life back into economics, Polity Press.

Holland, J. H. (1995). Hidden order: How adaptation builds complexity, Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Hull, D. (1990). Science as a process: An evolutionary account of the social and conceptual development of science, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kauffman, S. A. (1993). The origins of order: Self-organization and selection in evolution, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Kauffman, S. A. (1995). At home in the universe: The search for the laws of complexity, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Kay, J. (1993). Foundations of corporate success: How business strategies add value, Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Kuhn, T. S. (1962/1996). The structure of scientific revolutions, 3rd edition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lewin, R. (1992). Complexity: Life at the edge of chaos, New York, NY: Macmillan.

Lissack, M. R. (2003). “The redefinition of memes: Ascribing meaning to an empty cliché,” Emergence, 5(3): 48-65.

Lloyd, T. (1990). The nice company, Bloomsbury.

Lodge, D. (1988). Nice work, London, UK: Secker & Warbu.

Logan, K. R. (2004) The extended mind: Understanding language and thought in terms of complexity and chaos theory, http://www.physics.utoronto.ca/undergraduate/JPU_200Y/Logan_Book/em-table-of-contents.html.

Lord, A. S., Lunn, S., Price, I. and Stephenson, P. (2002). “Emergent behavior in a new market: Facilities management in the UK,” in G. Frizelle and H. Richards (eds.), Tackling industrial complexity: The ideas that make a difference, Cambridge, UK: Institute of Manufacturing, pp. 357-372

Marsden, P. (1998). “Memetics and social contagion: Two sides of the same coin?” Journal ofMemetics - Evolutionary Models of Information Transmission, 2, http://www.cpm.mmu.ac.uk/jom-emit/1998/vol2/marsden_p.html.

Mingers, J. (1994). Self-producing systems: Implications and applications of autopoiesis, London, UK: Plenum Press.

Mintzberg, H. (1994). The rise and fall of strategic planning, The Free Press.

Morgan, G. (1996). “An afterword: Is there anything more to be said about metaphor?” in D. Grant and C. Oswick (eds.), Metaphor and organizations, London, UK: Sage, pp. 227-240.

Pascale, R. T. (1990). Managing on the edge, New York, NY: Touchstone.

Powell, W. W. and DiMaggio, P. J. (eds.) (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis, London, UK: Chicago University Press:.

Price, I. (1995). “Organizational memetics? Organizational learning as a selection process,” Management Learning, 299-318.

Price, I. (1999). “Images or reality? Metaphors, memes and management,” in M. R. Lissack and H. P. Gunz (eds.), Managing complexity in organizations, Westport: Quorum Books, pp. 165-179.

Price, I. (2000). “Benchmarking higher education and UK public sector facilities management,” in N. Jackson and H. Lund (eds.), Benchmarking for higher education, Milton Keynes, UK: Open University Press, pp. 139-140.

Price, I. (2002). “Can FM evolve? If not what future?” Journal ofFacilities Management, 1(1): 56-69.

Price, I. and Evans, L. (1993). “Punctuated equilibrium: An organic metaphor for the learning organization,” European Forum for Management Development Quarterly Review, 93(1): 33-35.

Price, I. and Kennie, T. R. M. (1997). “Punctuated strategic equilibrium and some leadership challenges for university 2000,” 2nd international dynamics of strategy conference, SEMS Guildford.

Price, I. and Shaw, R. (1996). “Parrots, patterns and performance: The learning organization meme,” in T. L. Campbell (ed.), Proceedings of the third conference of the European consortium for the learning organization, Copenhagen.

Price, I. and Shaw, R. (1998). Shifting the patterns: The new science of organizational memetics, Chalfont : Management Books 2000.

Raup, D. (1992). Extinction: Bad genes or bad luck? New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company.

Rothschild, M. (1992). Bionomics: The inevitability of capitalism, Futura.

Scarbrough H., and Swan J. (1999). “Knowledge management and the management fashion perspective,” British Academy of Management Refereed Conference, Managing Diversity, Manchester, http://bprc.warwick.ac.uk/wp2.html.

Scott-Morgan, P. (1994). The unwritten rules of the game, New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Tylecote, A. (1993). The long wave, London, UK: Routledge.

Waldrop, M. M. (1992). Complexity: The emerging science at the edge of order and chaos, New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Weaver, W. G. (1998). “Corporations as intentional systems,” Journal of Business Ethics, 17(1): 87-97.

Weeks, J. and Galunic, C. (2003). “A theory of the cultural evolution of the firm: An intra-organizational ecology of memes,” Organization Studies, 24(8): 1309-1352. Whittington, R. (1993). What is strategy and does it matter? London, UK: Routledge.

Williams, R. (2000). “The business of memes: Memetic possibilities for marketing and management,” Management Decision, 38(4): 272-279 Winograd, T. and Flores, F. (1987). Understanding computers and cognition: A new foundation for design, Ablex Corp.